Austin Martin White

in conversation with John FM

Austin Martin White: I have been making a series of paintings about partying at the end of history. A primary source for the images has been Native American war dances, as well as images of ’90s raving — I chose these sources because they are both depictions of dance at the end of a historical era. The etchings of the war dances themselves are meant to document dance traditions that would soon disappear with Western expansion and the eradication of the peoples depicted in them. The figures in the ’90s rave images have a similar anxiety; we can assume it is in anticipation of the turn of the millennium. I feel that we are in a similar moment now, I feel that we are at an ending — and I am interested in how you feel rave/club culture has changed post-pandemic? I have my own experience — but I feel that it pales in comparison to your experience over the past couple of years.

John FM: In moments of hope, I think of the last protected dance floors. For Black people, I would argue that the last protected dance floor is the roller rink — an activity that expanded into dance, with different regional styles and a focus on Black music. It was once a place that was protested against in the ’50s and ’60s, the civil rights era, when Blacks were designated a specific night when they could skate separately from their white counterparts. Eventually the ’80s hit and the roller skate gave way to the invention of the roller blade, something that — from my perspective — white America became partial to. Though this was happening, skate nights in Black culture strengthened in Detroit, becoming as commonplace a family activity as bowling or barbecues. Furthermore, the activity itself even shows glimpses of progressive thinking via a comfortability between Black males. The patriarchal culture, exacerbated by behaviors learned and passed on from generation to generation by slave trauma, dissipates when groups of Black men join together, literally hand in hand, to dance on the roller rink floor, which promotes itself as a safe space for all peoples to dance, sweat, and peacock as hard as they can, impressing passers-by gawking outside the rink. The protective layer oftentimes comes from their inability to learn how to use roller skates themselves, and to look good on them at that. Traditions passed down from elder to child.

Few and far between am I able to spot places, even in Detroit, that embrace this sense of tradition, a freedom from the plights that American culture propelled to create a sense of belonging to all people. The club is collapsing because the entity of community is overlooked in favor of the dollar most of the time. The real moments feel tangible in Black-owned or ran promotions, which continue these Black, Brown, and queer-adjacent traditions of rave culture. They happen and are happening. Detroit is equally big enough and small enough to continue these things as such, in ways that a lot of other cities in America cannot, in a way that European culture tries to emulate.

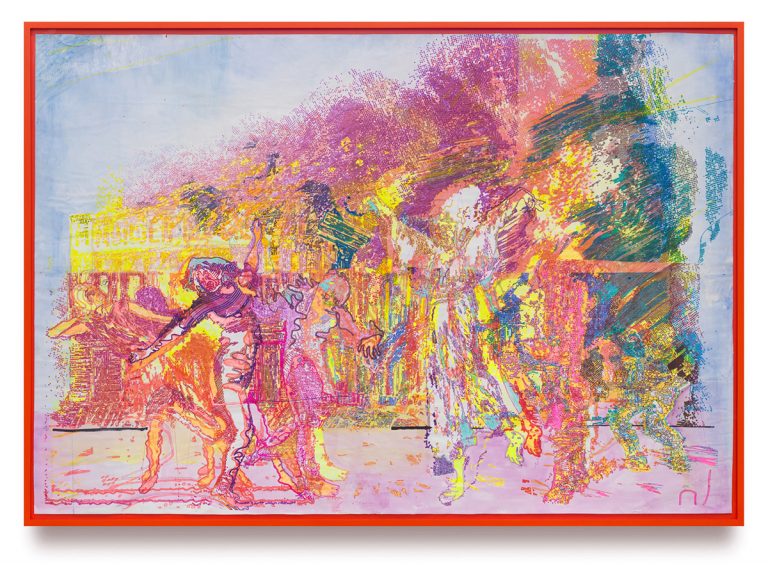

Austin Martin White, fireatthechurchofclubs (Bye Bye Berghain), 2022, watercolor and ink on paper, framed: 147 x 209.5 cm. Courtesy the artist and Capitain Petzel, Berlin

AMW: What do you think about the notion of techno or electronic music as a world-unifying culture conceived among the slow industrial death of Detroit?

JFM: Techno is an art form, born from an Afrofuturistic perspective on the ongoing urban decay of America. It’s a question posed: Where will Black people be in the ever-expanding technological advances that eventually turn into electronic junk and wiring? It is made from the sounds of crushed metals, bent by plant workers, aided by robots that will eventually rule the necessity of humans on the assembly line as moot. Ultimately there is no unification via techno without these ideas in the minds of the people claiming it and celebrating it through dance.

Austin Martin White, Revelation (fordlandia), 2022, watercolor, ink, rubber, pigment and screen mesh on paper, framed: 209.4 x 146 cm. Courtesy the artist and Capitain Petzel, Berlin

AMW: Do you think the ominous thought of climate change has had an effect on the electronic music scene? Do you think there is much self-reflection among people in the scene about their role as global ambassadors, how their presence (touring to exclusive locations such as Ibiza and Goa) may be ultimately harmful to the planet via their carbon footprint? Do you think, among the artists or event organizers who are aware of their role in the climate crisis, that they are stricken with a mood of “doom”?

JFM: There feels like an unfortunate fortitude in the thought of impending doom that leans heavily on ideologies of nihilism. It brings me to the song “1999” by Prince. The story goes that he was in a hotel room watching some religious end of the world TV segment that predicted the world ending in 1999, thus “so tonight we’re going to party like it’s 1999” is akin to partying like there is no tomorrow. On the other hand, these dance floors cultivate a conversation to be had about what can be done to fight these issues, what appears to be the closest existential threat within our control, and so in part, it is an artist’s or a performer’s unspoken duty to bring up these questions by pushing a narrative, in my opinion. And another counterpoint to that is when a person feels their purpose and true joy is beginning to allow them to live on that, it’s hard for them to look backwards and subject themselves to 9-5 work again, disabling them from experiencing the free thought that is afforded by periods of lull in the arts. Under capitalism, it’s all very hard to answer simply.

Austin Martin White during the installation of Last Dance at Capitain Petzel. Photo: Rosa Merk

AMW: We are both biracial and somewhat racially ambiguous or passing—how do you think Detroit as a societal entity has corresponded to or affected your own conception of your identity? Does identifying with the electronic music scene help you reach a better understanding of yourself identity-wise?

JFM: I think being in close proximity to Detroit has thrown any doubts about my identity and my Blackness out the window. The state of America—and which side I empathize with more — is consistent with that of Black Americans. I’m aware of my privileges, of being lighter skinned than some of my comrades and how that affects my everyday life, but ultimately, being from the Blackest city in America, I’m speaking the same language; my experiences may be a bit distant but hey are most certainly adjacent to the struggles of those with more melanin. I think seeing how diverse OR segregated dance floors can be opened my eyes a bit more to the colonization of what were once cherished Saturday nights belonging to POC and LGBTQUIAPK+ communities. If anything, I think my participation in these spaces reaffirms my Blackness.

Austin Martin White during the installation of Last Dance at Capitain Petzel. Photo: Rosa Merk

AMW: How do you think the residual effects of the pandemic will affect electronic music in the future?

JFM: Speaking on the ways that the pandemic already has—artists relying on government assistance to make ends meet because live shows were closed down for a while, multiple establishments shutting down permanently in the process. Thinking of how, now that people are on the “other side” of the pandemic, there is a doubling down on the aspect of how people choose to use their time, and what people do or don’t realize about the associations that confirm their identity in the spaces electronic music provides. People are ready to cut the bullshit and get right to the heart of the matter: joy. Joy on the dance floor.