Emily Wardill

Soft Spot

Emily Wardill, Game Keepers without Game, film still, 2009. Video projection with 5.1 sound, 72 min. Courtesy the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

carlier | gebauer is pleased to announce Emily Wardill’s solo exhibition Soft Spot. Soft Spot is Emily Wardill’s fourth solo exhibition with the gallery and will present two works by the artist, I gave my love a cherry that had no stone, 2016, and Game Keepers without Game, 2009.

Holding in her mind Dorothea Tanning’s painting Some Roses and their Phantoms (1952) and its sickening presentation of objects as between states of being, Wardill made with I gave my love a cherry that had no stone, a film that also hovers between definitions. The architecture of the Gulbenkian auditorium in Lisbon, its colours and sense of being lost in time accompany us through a loop where a man wanders the building at night, followed by something that is not human. Through the care and paranoia with which she approaches the digital image, the artist investigates the haunting of the present by the past and the remnants of textures longing to be touched.

Text by Ian White

Wardill may not have imbibed the same Marcusian grape juice that I have, but she has reckoned with the fact that, as an artist, she enables herself to “think about things like moving image and narrative socially, critically, politically, philosophically, and historically and step outside of a line of inevitability.

Marta Kuzma (Dean. Yale art school). 2020.

Emily Wardill, Game Keepers without Game, film still, 2009. Video projection with 5.1 sound, 72 min. Courtesy the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

Over the years Wardill’s films staged wide-ranging forms of individuation whose sense of continuity always appeared to be contested – forms in which “the ego is as impermanent as the body”; making graspable that, as Mach observes, “what we fear so much in death, the destruction of permanence, already occurs in life in abundance.

Excerpt from “The Life of Pseudo Problems” by Kerstin Stakemeier. 2020.

Emily Wardill, I gave my love a cherry that had no stone, 2016. HD video with sound, 8 mins. A production of the Centre D’Art Contemporain Geneve for the Biennal de l’Image en Mouvement, 2016. Courtesy the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

Emily Wardill, Game Keepers without Game, film still, 2009. Video projection with 5.1 sound, 72 min. Courtesy the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

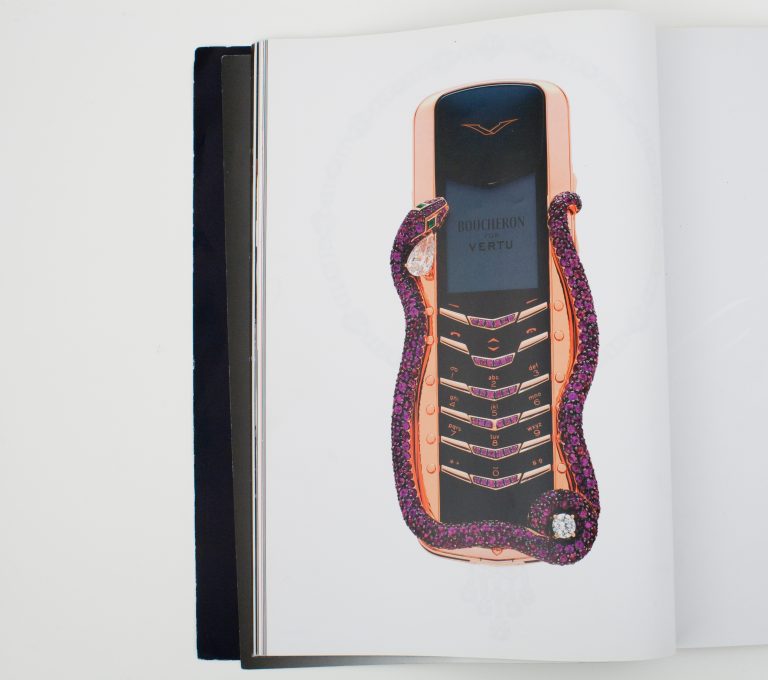

Game Keepers Without Game is a film set within the structure of a feature length melodrama. Formally based on the Spanish dramatist Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s Play La Vida es Suena (Life is a Dream), it follows the narrative of the return of a child who had been banished from the family home. Translated into contemporary British life, the film is comprised of a mixture of acted scenes where nothing and nobody touches each other. Still shots of objects fluctuate between being status symbols, evidence of crime and theatrical props. A drumming sound track builds up and breaks down like the building of a house.

Emily Wardill, Studio view, 2021. Courtesy the artist

Tarik Kiswanson

Surging

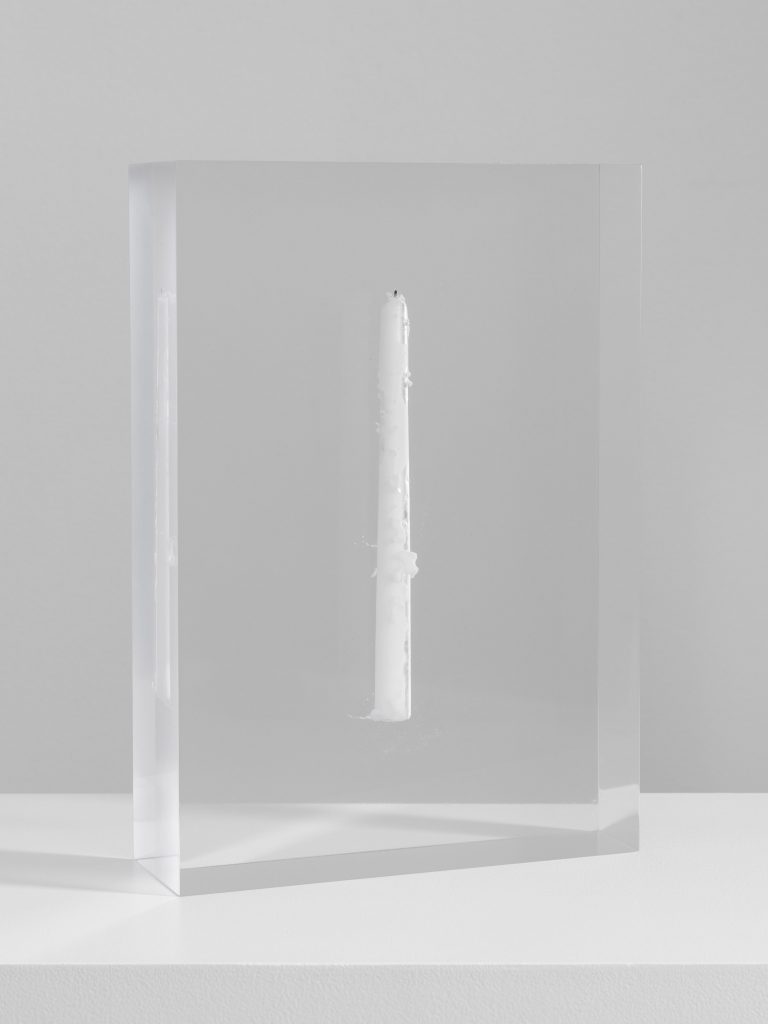

Tarik Kiswanson, Respite, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid. Photo: Vinciane Lebrun.

Postcolonial theorist Homi K. Bhabha wrote that the humanist writer must evoke “the empty space of erasure and extermination: of missing persons, destroyed things, hidden histories, lost records, expropriated lands, murdered minorities… without filling these absences.” We might argue that Kiswanson’s sculptures result from an intimate understanding of this humanism—they return to and emerge from a void.

Annie Godfrey Larmon – Writer and Editor

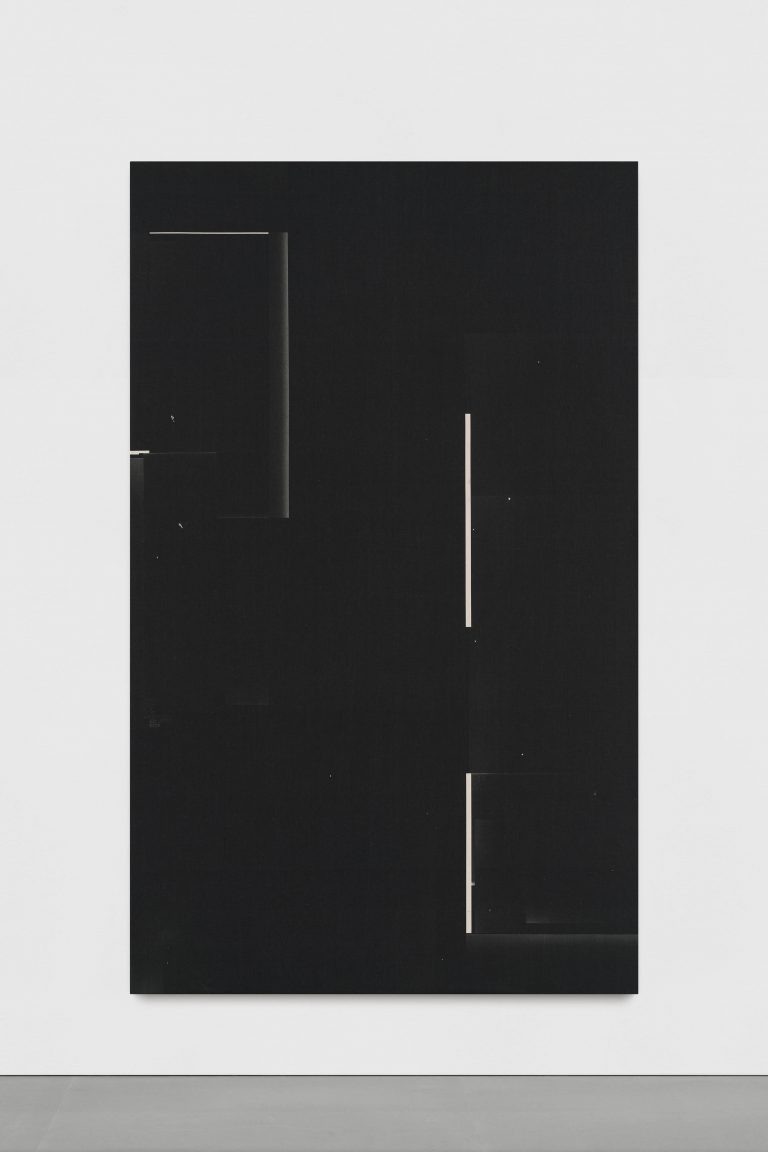

Tarik Kiswanson, Assembled Opacity, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid.

Tarik Kiswanson Cradle, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid.

To enter Tarik Kiswanson’s exhibition at carlier | gebauer is to experience a wider paradigm shift: the loss of grand anthropocentric narratives and the crisis of human singularity itself. In his previous works, the Swedish-Palestinian artist extended the transient experience of a first-generation migrant to the condition of the present-day individual, as one increasingly left to navigate a set tumultuous, global realities.

In 2017, his last exhibition at the gallery presented a series of reflective, ever-shifting metal vessels which, by defamiliarizing our perception, also dismembered the illusion of a fixed, finite self. While it furthers such investigations, Surging, Kiswanson’s third solo exhibition at the gallery, suspends pre-existing time and space. Through a speculative act of worldbuilding, it opens an elsewhere: a suspended context of its own. In the redesigned gallery space, a tight alley leads into the main room, reminiscent of a waiting room, which duplicates into a smaller cell-like structure sealed by a closed door.

At first, it remains unclear whether this transfixed environment, achromatic as if bloodless, indicates the aftermath of an extinction, an ongoing catabolic suffocation or the premises of a new birth. Surging materializes Kiswanson’s recent investigations into life and death, mutation and stasis, where beings – human and non-human, interspecies and post-human — adapt to survive in our precarious and troubled present. What is reborn is born in transit, what takes shape can only survive afloat.

Text by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Tarik Kiswanson, installing his solo exhibition “Mirorrbody” at Carré d’Art Nîmes, 2020. © Tarik Kiswanson

Tarik Kiswanson, installing his solo exhibition “Mirorrbody” at Carré d’Art Nîmes, 2020. © Tarik Kiswanson

Kiswanson’s work exists in interstitial spaces, but the interstitial isn’t cast as a smaller action between two larger ones. It is where it all unfolds. He animates these spaces and peels back the friction at the seams. There is a good claustrophobia in his work—you are inside it, and it is inside you, and then a third force field emerges from within that chamber.

Asiya Wadud, Poet and writer

-

Tarik Kiswanson Passing, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid.