Agnes Scherer

My refuge, my treasure, without body, without measure

Agnes Scherer’s site-specific installation My refuge, my treasure, without body, without measure arranges anthropomorphic containers in order to construct discursive allegories around human life and its exploitability. Inspired by the poetic possibilities of object theatre, Scherer orchestrates her paintings and sculptures within ChertLüdde’s gallery space to create suspense and surprising effects. An aesthetic framework animated by the summery palette of Florentine Renaissance ceramics is undermined by a calamitous logic which reveals itself to the closer look. As she playfully investigates iconographic traditions, Scherer represents human life by a variation of forms which are defined by their potential for holding content, and more importantly, to be cracked open. Sized up and weighed by superior decision makers, living treasure chests appear baffled between the promise of their own, unyielded contents and the implication of their extraction at the price of a compromised shell. Following a deliberate misappropriation of apocalyptic iconography through to its end, Scherer wrests from it a thought-provoking conclusion. While eluding a final interpretation, the equivocal allegorical play of My refuge, my treasure, without body, without measure touches upon questions around redemption, the capitalization on emotional life and artistic vitality as well as the vulgarization of content in the age of quantity-focused “content production”.

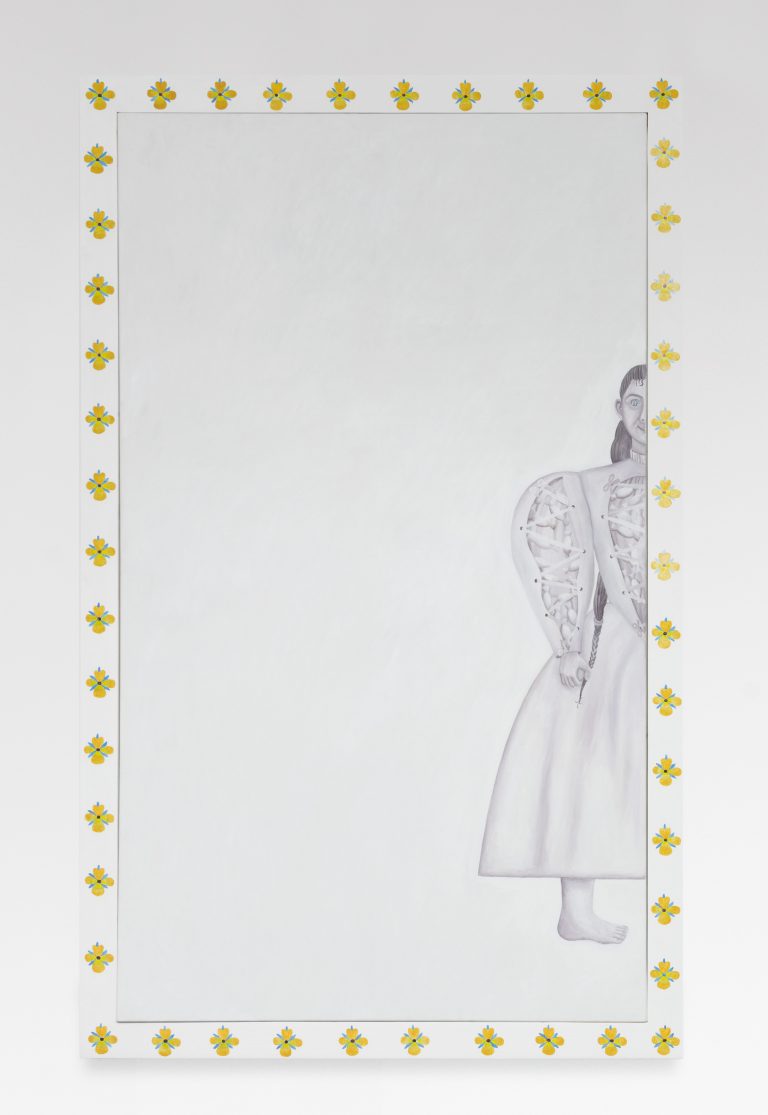

Agnes Scherer, “Bonbonnière (Ganzheit ist träumende Halbheit) (linke Seite)/ Bonbonnière (Wholeness is halfness that is dreaming) (left side)”, 2021. Photo by Andrea Rossetti. Courtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin and Agnes Scherer, Berlin.

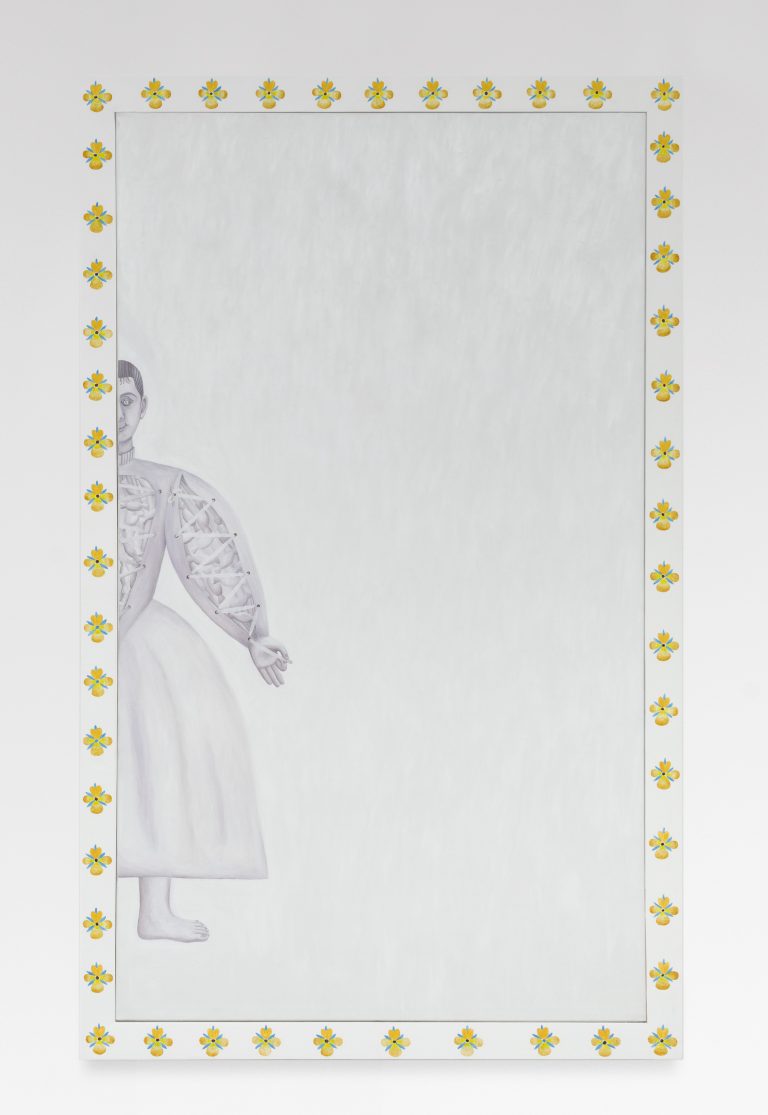

Agnes Scherer, “Bonbonnière (Ganzheit ist träumende Halbheit) (rechte Seite) / Bonbonnière (Wholeness is halfness that is dreaming) (right side)”, 2021. Photo byAndrea RossettiCourtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin and Agnes Scherer, Berlin

Initially trained as an art historian, Scherer marshals a dizzying array of visual references. Baroque mechanical theatres and catholic processions collide with PowerPoint presentations and snuff comics. But, channelled through her pastel-hued handiwork, the effect is less aseptically cerebral than altogether otherworldly

Stanton Taylor, frieze, 2019

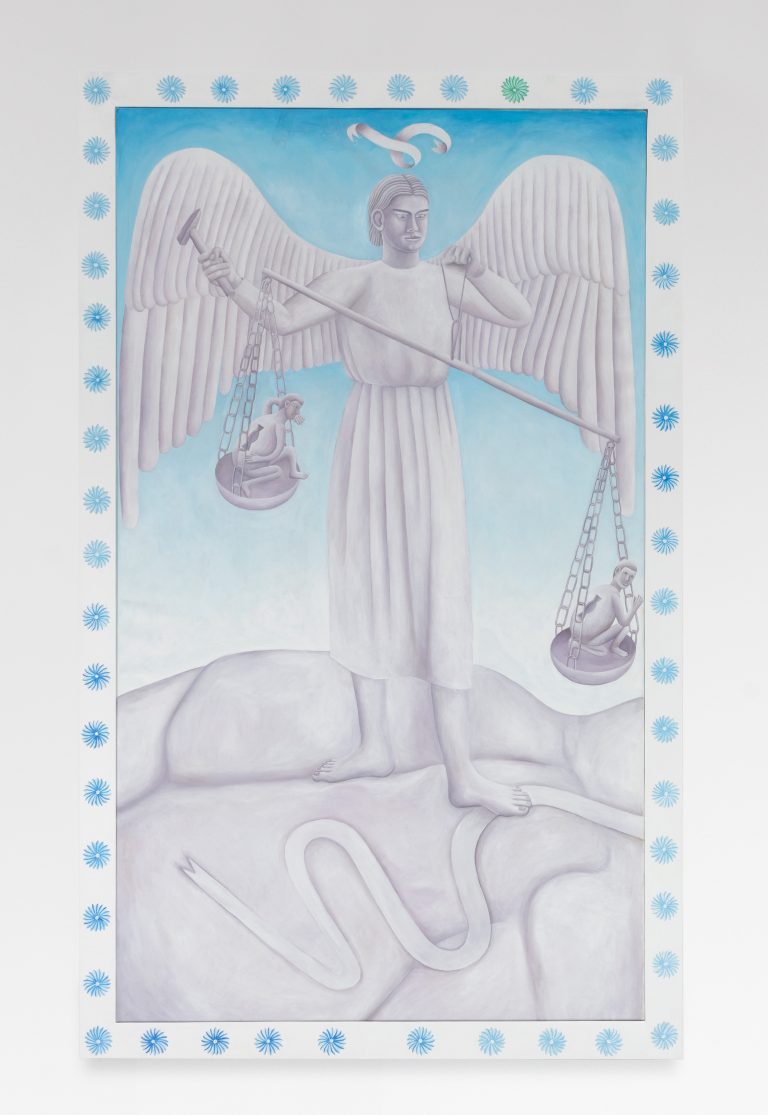

Agnes Scherer, “Große Psychostasie mit Banderolen (linke Seite)/ Large psychostasis with banderoles (left side)”, 2021. Photo by Andrea Rossetti. Courtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin and Agnes Scherer, Berlin

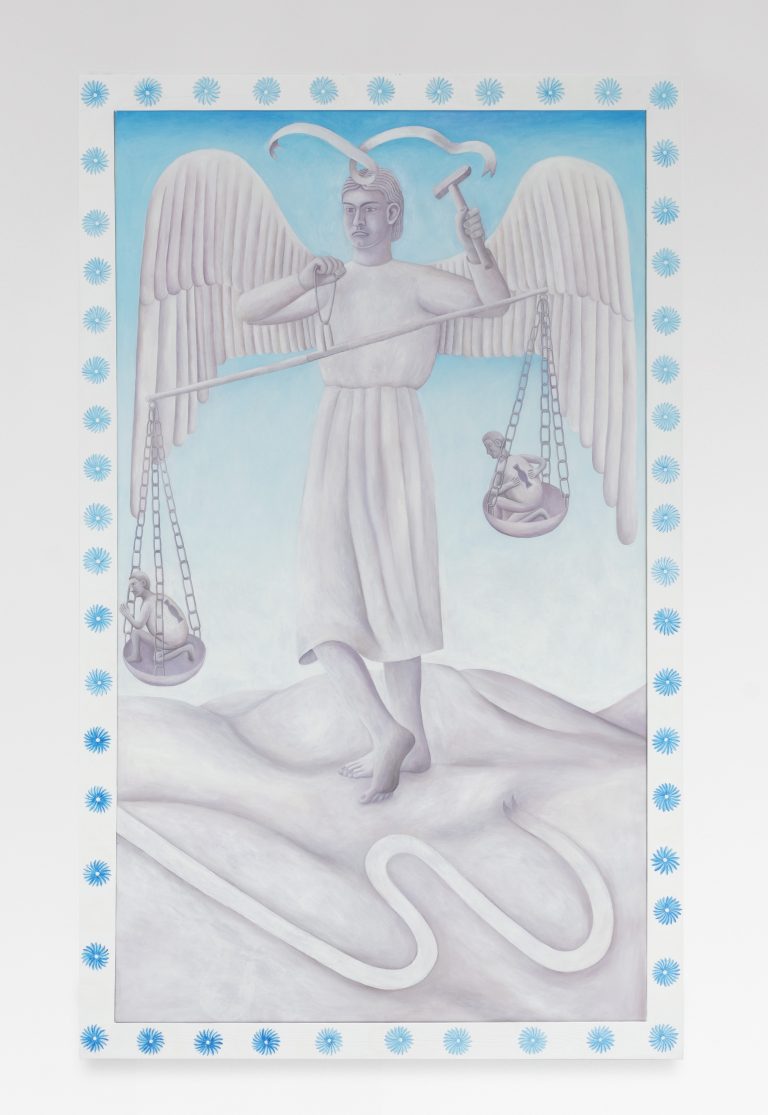

Agnes Scherer, “Große Psychostasie mit Banderolen (rechte Seite)/ Large psychostasis with banderoles (right side)”, 2021. Photo by Andrea Rossetti. Courtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin and Agnes Scherer, Berlin.

Agnes Scherer, The Teacher, installation view at Kinderhook & Caracas, Berlin, 2019; Photo: Trevor Good

Doruntina Kastrati

Here (Air Carries Poison But Yet We Breathe)

Doruntina Kastrati (b. 1991, Kosovo) presents a new video titled Here, filmed across various construction sites and national highways in Kosovo. Based on an earlier documentary narrating the stories of local construction workers, Here is a continuation of Kastrati’s ongoing research on the social political issues of Kosovo and the Balkan region, starting from the lives of affected individuals who experience outrage, desolation and indignity from being exploited in order to pave a growing city. The film displays a dizzying, alienating perspective of the country, whose concrete infrastructure overshadows and obscures its people.

Doruntina Kastrati, “HERE (AIR CARRIES POISON BUT YET WE BREATHE)”, installation view at BUNGALOW, 2021, Berlin. Photo byTrevor Lloyd Courtesy of BUNGALOW/ChertLüdde, Berlin and ChertLüdde, Berlin

Doruntina Kastrati, “HERE (AIR CARRIES POISON BUT YET WE BREATHE)”, installation view at BUNGALOW, 2021, Berlin. Photo by Trevor Lloyd Courtesy of BUNGALOW/ChertLüdde, Berlin and Doruntina Kastrati, Prishtina.

The exhibition includes new sculptural works made from 3D scans molded after the bodies of injured workers, revealing areas of injury during workplace accidents. Constructed out of fabric, resin and wool, the works invite discourse on the dissonance between official workplace policies in Kosovo and the exploitation that takes place within the private sector.

Kunstverein Hamburg, installation view, ‘‘Not fully human, not human at all”, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and HAJDE! Foundation. Photo: Fred Dott

Kunstverein Hamburg, installation view, ‘‘Not fully human, not human at all”, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and HAJDE! Foundation. Photo: Fred Dott

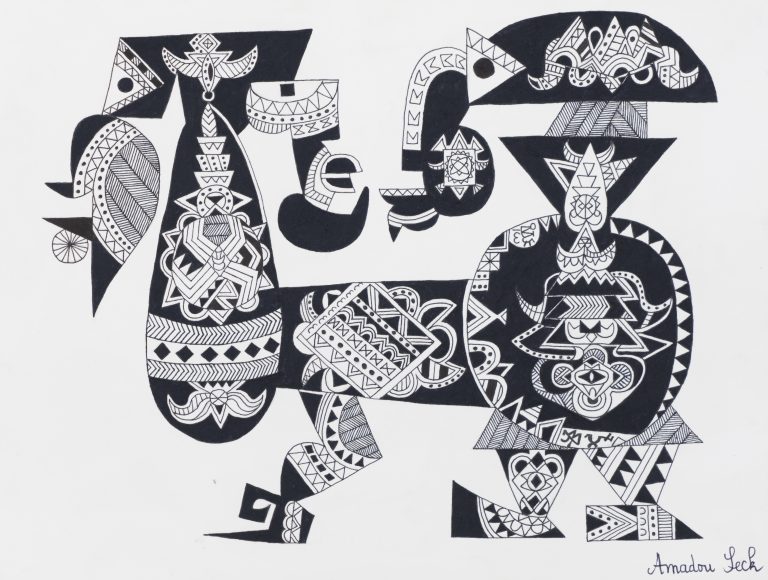

Amadou Seck

Amadou Seck, Untitled, 2020. Courtesy ofThe Artist and ChertLüdde, Berlin

ChertLüdde is honored to present an exhibition of ink drawings on paper by Senegalese artist Amadou Seck.

Amadou Seck, born on January 10, 1950 in Dakar, is a painter from the first generation of the Dakar School. With his semi-abstract style, incorporating elements associated with the school where he developed his practice, Amadou Seck is an important name of the epochal artistic group formed in Dakar around 60 years ago.

Between the mid-sixties and mid-seventies, Seck attended the school of arts in Dakar under the teaching class of Pierre Lods. Lods’ instruction relied heavily on the study of traditional African artifacts, based on his belief that modern art (1) in Africa should be seen as a continuity of traditional African art, free of European influences. The work of Amadou Seck is often celebrated as one of the most prominent examples of this artistic group.

However, the school was not free of controversy, one of them being Lods’ essentialist subscription to the notion of an “African” creativity, especially in the context of his own role as a European instructor:

“In the 1960s, when most African countries gained independence from European colonial powers, the artistic expression of renewal became a matter of urgent concern – and controversial discussion. Debates centered around the need to accommodate African art histories and visual traditions while reconsidering the role of European methods in arts education on the African continent. Through its special structure and constellation of people, the art school in the Senegalese capital Dakar came to be the site where these issues manifested themselves most clearly.” (2)

Growing in a newly free Senegal, influenced by the cultural ideology of President Léopold Sédar Senghor, artists within this cultural movement embraced Africa’s postcolonial engagement with the rest of the world. Working primarily with paint, and in an overtly abstract and decorative manner, the group of artists under the umbrella of the Dakar School enjoyed for several years the support and patronage of the government and international recognition.

Amadou Seck joined the school from 1966, upon introduction by Ousmane Faye (3), and remained actively involved there until 1974. In 1977, he took part in Festac ’77, the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, the major international festival held in Lagos, Nigeria. In the 1980s, Seck painted significant large-scale works and exhibited internationally. During his time at the school he also produced some examples of “tapisserie” (tapestry) works taught in the workshops, most of which are now held in the Senghor collection.

Although he never ceased in artistic production, the last international exhibition of his work was during the 1980s, in expositions organized by the Senegalese Committee for Exhibitions Abroad:

“In order to promote art abroad, Senegal created a particular institute; The Committee for Exhibitions Abroad. The first large exhibition took place at the Grand Palais in Paris from 26th of April till 4th June 1974. It was an event for a Europe ignorant of modern African art, enchanted with its own conception of Africa as a continent whose works of art, taken up by Picasso and his followers, culminated in sculptures and masks.

The Committee aimed at making Senegalese art known in Africa and beyond its borders. Finally, it was aiming at an inter-cultural dialogue, a principle of the Senegalese cultural politics since independence. Poet-President L. S. Senghor arranged the annual Salons for Senegalese artists. After two Salons and strict selection, the national art collection was compiled and exhibited in the Grand Palais in Paris. This was the inauguration of the “School Dakar” in the international art scene. The Paris media welcomed the young artists whose average age was 26. Senegalese art has ever since been represented in many of the world’s largest and most important galleries and museums.” (4)

For his first solo exhibition in Germany, Seck created several new black ink drawings on paper, constructing an imagery around African mythology and cosmogony. The drawings depict elaborate motifs referring to traditional rituals, religion and myths in West African cultures. Seck’s rich visual vocabulary details various traditions in West Africa such as Ashanti fertility figures or the gods and natural spirits of the Yoruba people. Recurring figures in the drawings have multiple heads, limbs and wings, suggesting animal-human hybrids whose faces and bodies are adorned with delicate ornamentation. Double masks representing marriage or twins, animals such as buffalos, antelopes, sharks and hippos surface in his magically layered and emblematic portraits.

“I made my bones by drawing with charcoal on the walls of Colobane, my district,” says Amadou Seck. The artist’s drawings, incredibly refined and varied, reflect his own creative process as formed by a constant inner intuition and inspiration, in which the drawings come together to construct a fascinating language.

We would like to extend a special thanks to Fatou Seck, daughter of Amadou Seck and Mohamed A. Cisse for their help and support in coordinating the realization of the exhibition.

This exhibition is dedicated to the memory of Laura Croci (1949 – 2020), whose life circumstances led to this encounter.

(1) In the discussion surrounding Modern African Art we quote part of Chika Okeke’ s essay Modern African Art, in The Short Century – Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945-1994, ed. Okwui Enwezor.

“What does modernism mean in the context of twentieth-century African art? First, modernism here is tied to the rise of modernity in the African continent, which is in turn connected to the colonial experience. In other words, as colonialism made European material culture and ideas more available, artists from the colonies invented new artistic expressions that reflected Africa’s encounter with Europe, and also with the rest of the globe. Whether through an essentialist nativism or a supposedly progressive adoption of patently European aesthetic styles and propositions, the resulting work bore the unmistakable mark of the artists’ twentieth-century-ness. Much as in the heyday of Paris in the early twentieth century, artists from all corners of the world converged in the French capital in the interwar period to share philosophies and aesthetic positions.In the climate of an art and intellectual world peopled by émigrés (Picasso, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Samuel Beckett, Aime Césaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Fanon), the work evolved out of diverse colonial conditions, past the ravages of colonialism, and finally through the dramatic experience of decolonization. African modernism is defined by the conflation—rather than by any single one— of these episodes, and by the art forms and aesthetic ideas associated with them. The obvious implication is that African modern art does not propose a particular narrative of modernism, as the triumphalist European version did. In Africa one can even speak of a range of modernisms specific to the continent’s different countries”.

(2) From Judith Rottenburg, The École des Arts du Sénégal in the 1960s Debating Visual Arts Education Between “Imported Technical Knowledge” and “Traditional Culture Felt from Within”.

(3) Ousmane Faye studied at the National School of Arts in Senegal, at the School of Decorative Arts in Thiès and at the School of Decorative Arts in Aubusson (France). He has participated in numerous exhibitions around the world and has received several distinctions. He was made a Knight of the National Order of the Lion by the President of Senegal in 1999.

(4) The Exhibitions of Senegalese Contemporary Art Abroad, Djibril Tasmir Niane in Anthology of Contemporary Fine Arts in Senegal, Museum of World Cultures (Weltkulturen Museum), Frankfurt am Main, 1989