Editing the film as it screens

Blurred lines between drawing and film in the work of Heiner Franzen

by Kolja Reichert

In the entrance hall at Wannsee station in Berlin, to one side of the main pedestrian flightpath, stands a tall, thin object made of turquoise fabric with a trapezoid footprint. At one point, a pen presses against the shroud from inside, moves a few centimeters and traces a black line. The pen changes direction, still drawing the line, and then disappears. The onlookers watch the calm surface, waiting eagerly until the same thing happens a few centimeters away. The lines join to form a figure, the pen starts somewhere else, and over the course of 40 minutes a network of lines covers all four sides of the object.

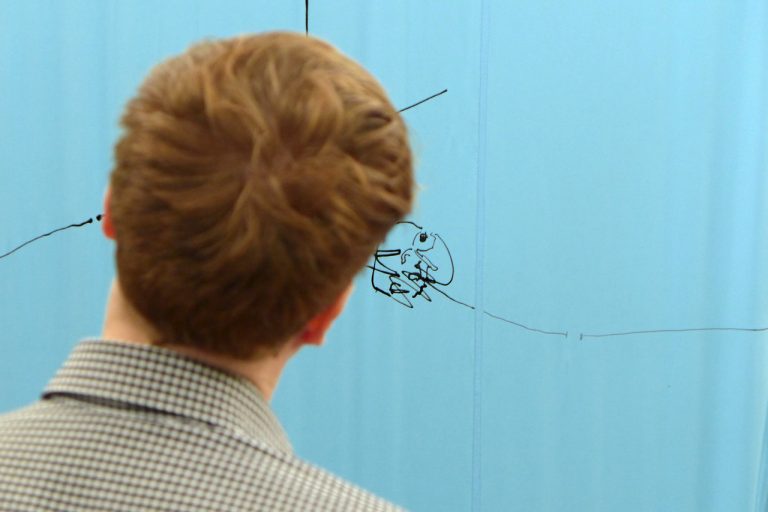

The action Kartenraum (2014), during which Heiner Franzen stands inside the fabric object, is cinema with the simplest of means: the fabric is the screen, his pen the projector, with a soundtrack of the scratching and squeaking of the pen’s tip on the fabric. Artist, hand and implement remain hidden, conveying their presence only by the trace that manifests itself on the surface. But they are also synchronized with the bodies of the viewers, who are steered around the object by the pen as if by magnetic force. Viewing here is clearly an affective, physical activity. The movement of drawing continues in the movements of the bodies, which become extensions of the animation medium. Production and reception cannot be separated, the animated film is captured as it is being made. But each individual image is permanently recorded on the screen, like the images of a film in the memory of the cinemagoer.

This process has far less to do with the transmission of specific pictures than with the writing movements of the light beams in the cinema itself. It is about more than accumulations of individual motifs; it does not refer to something that exists independently of it. Processes of memory and sensation are imprinted directly onto paper or wall, into the foam board or video edit. Franzen’s work is like a permanent process of Freudian dream distortion: not work on form, but form at work, in an ongoing open-ended stumbling. Some of the figures that flash up in the fabric in Kartenraum look familiar – having appeared in similar form in Franzen’s drawings of recent years, as well as on the walls and ceilings of his installations. They also covered the white fabric at Kunstverein Wolfenbüttel where Franzen returned to Kartenraum, this time behind a two-dimensional wall of fabric set diagonally in a room facing onto the street. They are fragile shapes drawn with quick, sketch-like strokes, on the verge of abstraction. Heads with one eye or none, their field of vision often obscured by planes resembling open books or VR headsets. A sprawling repertoire of such characters runs through Franzen’s drawings, reappearing in modified form, sometimes years later – like digital files changing as they migrate from one format to another. Each drawing is like a still from an inner film, played back in a feedback loop via various media, constantly re-editing itself.

Drawing is considered to be the most immediate means of artistic creativity, a direct dialogue between body and form. But as the increasing importance of space and process makes clear, Franzen’s practice goes beyond a narrow definition of drawing. Instead, he expands it to include the temporal dimension of film and, more recently, the physical dimension of performance. Every drawing, every collage, every installation, every object, every video is an excerpt from a projection that evolves over the years between the artist’s head, his studio and the various exhibition situations, constantly updating and rewriting itself in different media formats, while the film reel itself remains invisible.

As a former film projectionist, I can hear in my mind the clattering and flapping of analogue film on the projector reels, and through the projection window I see the slight jump of the picture on the screen as a splice with a tiny blank lurch over the sprocket. The illusion of linearity in analogue film, which always results from the viewer’s mind filling the gaps between the individual frames, is always subject to disturbances. In The Shining (1980), director Stanley Kubrick plays with this when Danny is presented to the twin girls who invite him to come and play. Four times, for the duration of just a few frames, a complementary scene appears showing the smartly dressed girls as massacred corpses lying on the floor.

This horrific image is at odds with the linearity that creates presence, like a sudden flashback to a traumatic experience that holds the traumatized person in a loop of unconquered fears. This is one of many film scenes that Franzen inserts into his drawings, mostly in fragmented and pixelated form, compressed and initially illegible. They interrupt the map-like graphic networks that stretch across the walls and ceilings of his house sculptures. The motifs themselves are traces of experiences in which the discursive order breaks down. “It’s not about the picture,” says Franzen, “but about what happens when the picture gets stuck.” In the two-channel video Twin (since 2009) Franzen also refers to Kubrick’s twin motif, this time in fragmented form: On the screen we see the feet of the twins as they turn to walk away. On the other side stands one of the girls in her dress, cut off at chest and knee level, facing the viewer, holding her sister’s hand. But Franzen has edited out the sister’s arm. While this breaks roughly with the creepiness of the doppelgänger look, it also heightens it by forcing it out of sight. The two brief sequences are screened as loops. The position, size and framing of the individual images change constantly, creating a permanent twitching — as with the endlessly galloping horse in the video Bliev Wech Van Mien Gerechtigkeit (since 2013) or the trousers floating in the sky in set (since 2013). Just as Franzen’s drawings resist gelling into a picture, his videos reject the unity of the film image. The twitching individual frames cannot resolve into linearity; film time and viewing time, film space and viewer space remain strictly separate; the film image becomes a drawing floating openly in time.

This is also how Franzen negotiates the crumbling lines between media forms. Walking through the 21-metre-long tunnel with a pitched roof that Franzen built into a sequence of rooms at Museum Schloss Moyland was an almost film-like experience, as the cramped space imposed a sequential reading of the cartoon-like collages of drawings and film stills. Franzen uses the house shape to represent the head, an externalization of the inner projection machine. This is also a possible reading of set, a legged object made out of foam board that projects a video onto its own hollow insides or onto a nearby wall. Just as Franzen’s drawings change over the years, and just as he adds new edits to existing versions of his videos, sculptures like these appear in new forms depending on the location.

One cannot see the top of one’s own head (Leonce, in Georg Büchner’s Leonce and Lena). One cannot be what one says (Lacan). One cannot merge with the cinematic gaze (Jean-Pierre Oudart*). We cannot access the code that generates our creativity. We can only try to get close to its operations while it is already in the process of rewriting itself. Ultimately, every experience of form and meaning is based on aporias, on pure events in which opposites become inextricably entangled. Franzen’s work unfolds along these aporias, along an unpredictable line like that of the felt-tip pen in Kartenraum.

This text was written in 2014 and first published in Franzen’s catalogue #Millionenfotos, Verbrecher Verlag, Berlin 2017. Translated by Nicholas Grindell.