Gallery Portrait

PSM

Philipp Hindahl, APR 2024

Installation view: Christian Falsnaes, FEAST, 2021, PSM, Berlin

Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin

Image: Marjorie Brunet-Plaza

What looks like a dinner party, descends into chaos as food is tossed around, as walls, which prove to be not solid at all, are kicked in, and as guests in uniform white outfits paint the walls wildly and expressively. It all happens on the behest of Christian Falsnaes, and the event was a performance by the Danish artist, titled Feast, set up as a dinner at PSM to celebrate the anniversary of his collaboration with the gallery. The presentation testifies to the readiness with which the gallery shows work that defies the conventions of the art market.

Portrait of Sabine Schmidt on ‘Fantastic Plastic, Monobloc Chair (lila)’ by Nadira Husain

When founded in 2008 by Sabine Schmidt, PSM first occupied a space in a part of Berlin Mitte that feels distinctly like Prenzlauer Berg. The site in the former East had formerly been used as a garage for government vehicles, and while it may have been cold in winter, the rooms offered ample capacity for showing art. After four years, the building was due for demolition. The gallery moved to the southern reaches of Mitte, which border on Kreuzberg, before settling in its current space, right across from Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie, whose extension is set to open in a few years, and just off Potsdamer Straße, the epicentre for young and established galleries.

PSM set up shop in a pre-war building facing the canal that separates the districts of Tiergarten and Schöneberg and occupies a generous apartment with wooden floorboards and white walls. This is where I meet Schmidt on an overcast, stormy afternoon in early April. In a space overlooking the courtyard, which resembles a conservatory with its big windows encroached by vines, she tells me how the gallery opened the same year as the investment Bank Lehman Brothers folded. PSM, the name of the gallery, is derived from the company Paul Schmidt Medebach, founded by the art dealer’s grandfather, which had to close in the years of the financial crisis.

“The art market could not go any lower, but when you just start out as an art dealer, it matters a little less,” she tells me. “You don’t expect to sell out your shows right away—you need to build a name and a program first. I think the crash was more impactful to established dealers.” At the end of that decade, many galleries opened in Berlin, but not many survived the first few years. Schmidt attributes her resilience to the community of artists in her steadily growing roster and to the collectors who believed in PSM.

Installation view: Aziz Hazara, No Dress Code, 2023, PSM, Berlin

Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin

Image: Marjorie Brunet-Plaza

While studying anthropology and art history, Schmidt has been greatly influenced by Okwui Enwezor’s 2002 Documenta. “I’ve never had a singular vision with focus on specific themes or media. Rather, I am looking for authentic voices from different areas,” says Schmidt. For a long time before founding PSM, she worked as program coordinator at Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt, an institution that is traditionally interested in the meeting points of different cultures.

But, as is the nature of institutions, artists come and go once exhibitions and projects are over. Galleries, on the other hand, rely on long-term relations with their artists. One might expect the institutional world to have reservations towards the market, but really, both are intimately intertwined. Artworks that end up in institutional shows mostly are borrowed from private collections or galleries, and without art dealers, this system could not function. “I’ve always found it fascinating,” says Schmidt, “to see eye to eye with people, and to do the business directly.”

Berlin may be home to many galleries, but a truism about the city says that there is no viable art market. Schmidt disagrees. She asserts that there is a large number of young, politically aware, and adventurous collectors. Fittingly, PSM takes measures not to bolster the catalog with fair-friendly, easily marketable art.

Falsnaes, for example, is one of PSM’s best-selling artist, although he mainly produces things that are difficult to sell, conserve, and stage. Large museums have only recently begun to collect performance, and the Dane is present in a few public collections—among them the Centre Pompidou and the Kunstmuseum Krefeld—and his career has become a reference for other performance artists. “I told him, I’d like to represent him. Not as a figurehead for the gallery, but as an economically viable position.”

The artist and the dealer figured out how to draft certificates and facilitate the re-staging of performances. The pieces are accompanied by tutorials on video, and, Schmidt assures me, they could be presented 200 years from now. “It doesn’t have to be Falsnaes, although many people believe that. Anybody, who is fearless before a group of people and has seen the tutorial, can perform the pieces.”

Conserving the ephemeral may seem like a contradiction, but artists like that created the gallery’s exceptional position. “Unique practices interest me, because I believe that they will prevail in the end. It might just take a little longer because they don’t cater to trends.”

Installation view: Iris Häussler, Seventeen Grams of Longing, 2024, PSM, Berlin

Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin

Image: Marjorie Brunet-Plaza

Among those unique positions figures Iris Häussler, a Canada-based, German-born artist, whose show Seventeen Grams of Longing was on view when I visited the gallery. Häussler tells stories of fictional artists, and she does so by creating their oeuvre. Often enough, they are stories that could—or should?—have been told, along with found objects that have fallen through the crevices of art history. “Positions that I haven’t seen quite like that very alluring. That’s why my program doesn’t follow one specific topic, just like the artists focus on different things,” says Schmidt.

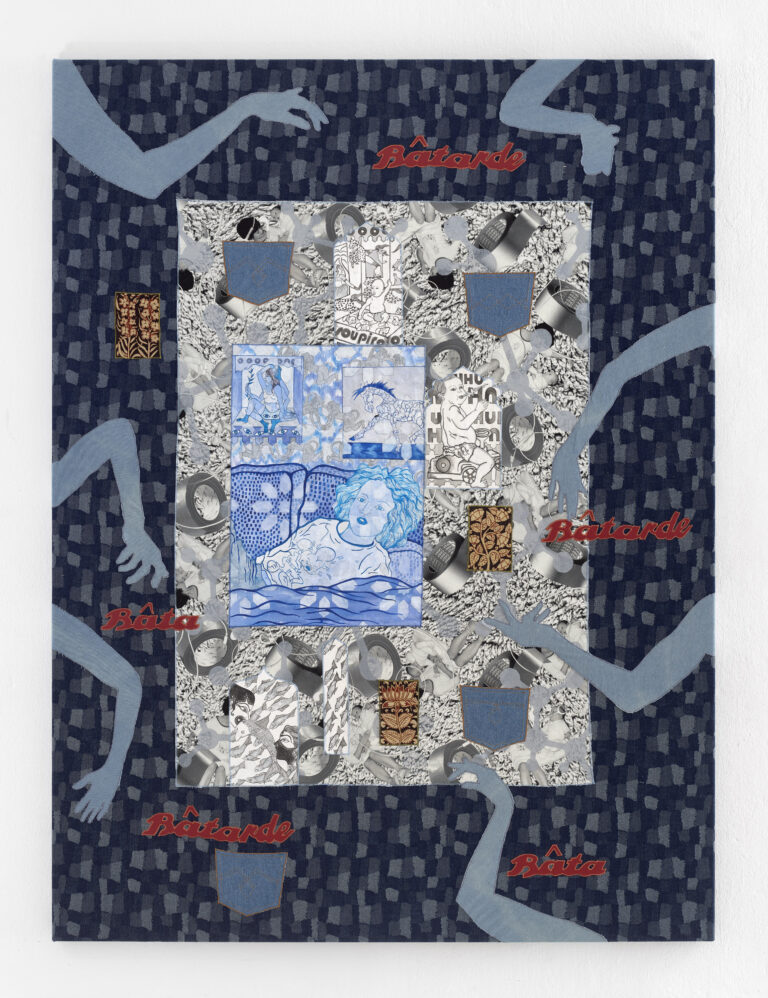

Nadira Husain

Global Bâtarde Education, 2024

Acrylic and ink, inkjet print on canvas, Kalamkari vegetable-dyed cotton fabric and sewn denim

200 x 150 cm

Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin

Image: Eric Tschernow

To Schmidt, it is essential that the pieces have an effect on viewers, which, she says, works best when the artists have internalized their subjects. “Just like Nadira Husain’s aesthetic, which comprises of elements from her own symbolic alphabet.”

Husain’s work, which incorporates different media will be on view for Gallery Weekend. One space in the gallery will feature three figures, composed of ceramic limbs and garment-like, large textiles that stretch all the way to the high ceilings, similar to a series of works Husain refers to as Ancestors. The works deal with migration—deliberate and forced—and the things migrants carry. Husain is fascinated by the cultural hybridity; she herself grew up in France while one of her parents is from India, and her work is rich with symbols and influences.

“Artworks that allow me to learn fascinate me,” says Schmidt as I leave. “The works can be beautiful, but they don’t have to. However, they need to have an effect on people, and that works best when artists have internalized their subjects.”

PSM

Schöneberger Ufer 61

10785 Berlin