Gerrit Frohne-Brinkmann

ILOVEYOU

Gerrit Frohne-Brinkmann, ILOVEYOU, 2021.

In 1998, the Hollywood movie You’ve Got Mail introduced a wider public to the idea of cyber-romance: the two protagonists anonymously begin a romantic relationship via messages exchanged over AOL. It was one of the first major film productions that incorporated the novelty of digital communication to make visible a fleeting moment of online culture when dial-up internet connectivity just got strong enough to spark a romance between two strangers.

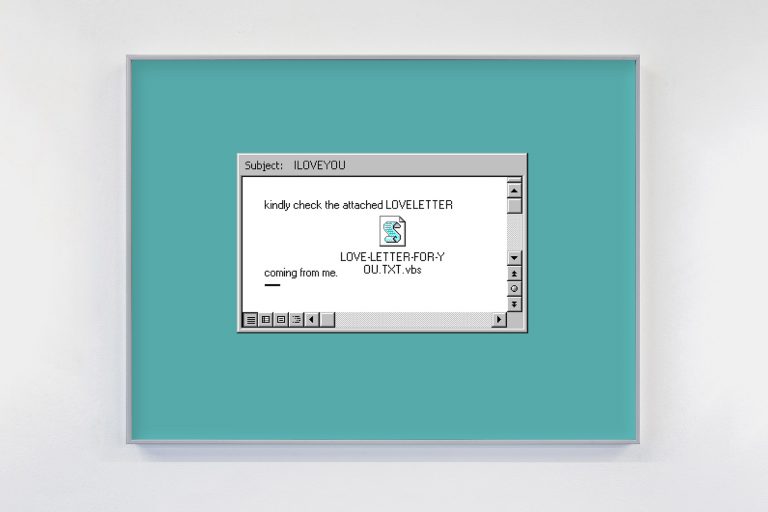

On May 4, 2000, users of Windows’ Outlook program began receiving an email with the compelling subject “ILOVEYOU,” but containing a malicious attachment disguised as a text file of a love letter. Once opened, the self-replicating code would overwrite or delete files, steal passwords, and automatically send copies of itself to everyone in the recipient’s contact list. Originated in the Philippines, the virus wormed its way into private, business, and government email systems around the globe, and within just days about fifty million computers were reportedly infected with the so-called Love Bug.

In both instances, the internet was still in its relative infancy and the comparatively small number of its users at the time were just becoming familiar with the new digital forms of communication. Some twenty years later, these have turned into a labyrinth of passions, self-(re)presentation, and exposure. Considering two decades of technological advances in corresponding online, the employment of digital love letters in popular culture, on the one hand, and their emotional exploitation, on the other, nowadays mainly evokes a sense of nostalgia.

It is a similarly nostalgic feeling that befalls us when entering Gerrit Frohne-Brinkmann’s fourth solo exhibition at Galerie Noah Klink. An image of the original email that invited the then-recipient to “kindly check the attached LOVELETTER coming from me” now welcomes the viewer. Continuing into the other space, various computer towers have been arranged on a pink carpet, some of them positioned close to each other, even facing each other as if in communication. By installing them on a campy display, the artist sets the machines into contrast with their outward appearances as well as their clichéd contextualization within a male connotated computer world, thus enabling a reception that goes beyond stereotypes. Frohne-Brinkmann has intentionally infected the machines with the ILOVEYOU virus, repeating the original gesture and essentially making them lovesick. The computer worm, which he obtained from an online archive of viruses and bugs, turns the cubes into carriers of “love letters” without addressee, only perceivable through the subtle sound of the fan, evidently making them into more than just ready-mades, but tangible representations of desires and human frailties. What was once considered to be one of the greatest digital threats causing systems to collapse is now, in the context of the exhibition, just a glimpse into the past, nothing more than a harmless historical relic.

The Love Bug was one of the first global cyberattacks to rely on psychological or, rather, emotional manipulation, and as such it utilized something far more powerful than just code: it took advantage of those errors and faults that emerge when the longing for being loved tricks us into a false sense of trust and comes to expose our vulnerabilities. With his new body of work, Frohne-Brinkmann traces the emotional, sociopolitical, and aesthetic dimensions of the virus and examines the diverse psychologies of human interaction and behavior in order to explore notions of desire and nostalgia, deception and disappointment.

Gloria Hasnay

Installation view, Gerrit Frohne-Brinkmann, ILOVEYOU, 2021, Galerie Noah Klink. Photo: Volker Renner

Installation view, Gerrit Frohne-Brinkmann, ILOVEYOU, 2021, Galerie Noah Klink. Photo: Volker Renner

When I look at Gerrit’s work, I oftentimes find it to reveal a kind of desire. A hidden desire engrained in material things, concealed by the veil of culture, is brought to the fore through his work in such a way that I forget to ever not having been able to see it. It is veiled, however, not because it is a shy lover’s desire which they hide for fear of being exposed, not the voyeuristic, secret-admirer kind of desire that straight dating apps turn into a product, and neither the sublimated, Freudian desire that turned itself into a product because it needed something to latch on to. It is a desire that may go unnoticed despite being overtly visible, for reasons that I don’t really understand but that might have something to do with the anthropocentric framework we normally use to regulate desire. There is, after all, not all that much difference between a human’s desire for something/somebody and, say, a clock’s desire for time, or a stalactite’s desire for the ground, or a dog’s desire for love. Or so I like to think when I see Gerrit’s work, that is.

Every kind of desire contains social, economic, environmental… relations in the sense that it is shaped by them. In turn, those relations can be read as reflections of the desires they shape. As I begin to see the desirous nature of technologies, of reason, of the history of ideas… – as I see how desire permeates all the way through, I lose track of desire’s outside. This can be bad, because it is always violent when desire disguises itself as something else or, vice versa, when something that is not desire acts as though it were. Maybe these lines are something that Gerrit’s work tries to think about when it renders everything so horny. ILOVEYOU is a show about horny computers, infectious diseases, absolute loss, and our nostalgia for a time when the world had just begun to contain the pandemic of another virus, one that killed millions of lovers, profoundly changing the structure of desire and the administration of love.

Elias Wagner

Installation view, Gerrit Frohne-Brinkmann, ILOVEYOU, 2021, Galerie Noah Klink. Photo: Volker Renner