VUL|NE|RA|BLE

with works by Anna Boghiguian, Candice Breitz, CATPC, Alice Creischer, Chto Delat, Clegg & Guttmann, Heinrich Dunst, Estate of León Ferrari, Peter Friedl, Sophie Gogl, Barbara Hammer, Ramon Haze, Hiwa K, Simon Lehner, Mario Pfeifer, Dierk Schmidt, Michael E. Smith, Franz Erhard Walther, Clemens von Wedemeyer, Tobias Zielony, Anna Ehrenstein & Rebecca Pokua Korang, Sophia Eisenhut & Max Eulitz, Hudinilson Jr., Pınar Öğrenci, Helena Uambembe

8 SEP until 16 NOV 2024

Opening – 7 SEP, 11 am

New address:

KOW

KURFÜRSTENSTR 145 —

ENTRANCE FROBENSTR

10785 BERLIN

KOW, Kurfürstenstraße 145 I Entrance Frobenstrasse, Berlin. Photo: Ladislav Zajac.

KOW celebrates its 15th anniversary and inaugurates its new home on Berlin’s Kurfürstenstra.e with 28 artists from 14 countries.

Vulnerable, 2024, exhibition view at KOW,

courtesy KOW, Berlin,

photo: Ladislav Zajac.

Chto Delat, Signal Flags, 2021, detail, “I am losing my roots, I demand critical support of comrades“.

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin.

Photo: Chto Delat.

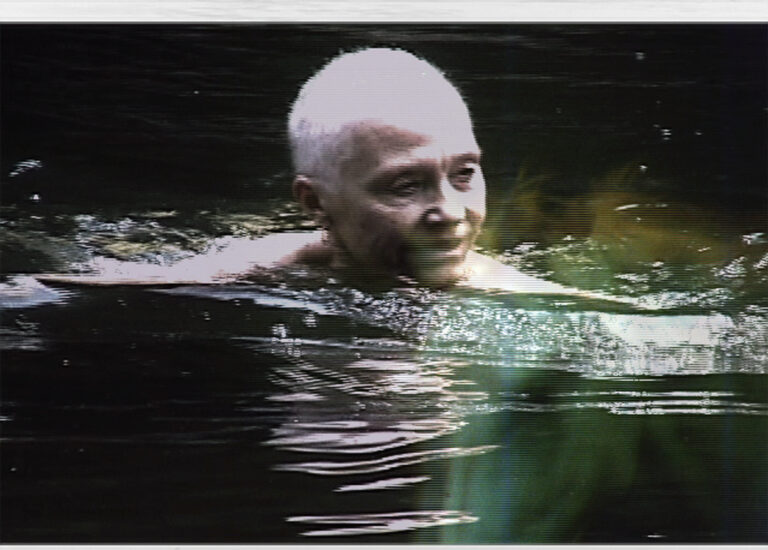

Barbara Hammer, A Horse Is Not A Metaphor, 2008,

courtesy the estate of Barbara Hammer and KOW, Berlin.

Amid turbulent times, we turn our attention to the delicate and vulnerable. With fragile and pensive works as well as ones that bristle with nervous energy, the exhibition probes the feeling of defenselessness and finds remarkable strength in creative stances that squarely confront the fact that human bodies and human-built orders are sensitive and open to attack. By turning the spotlight on their own and others’ vulnerabilities, the works in the exhibition create moments of empathy and allow us to touch on entrenched frontlines.

Vulnerable, 2024, exhibition view at KOW,

courtesy KOW, Berlin,

photo: Ladislav Zajac.

(31) In the gallery’s street-facing windows, Chto Delat (RU) present 16 semaphore flags, a format they have borrowed from ocean shipping (2024). But the matching legend makes no reference to rules of navigation—the flags indicate states of mind, sending personal messages of exhaustion, self-care, and furious anger. All members of the Russian collective Chto Delat now live in exile; some had to leave the country from one day to the next to escape imminent danger.

(1, 2) The two photographs from Tobias Zielony’s series Golden (2018) were taken in Riga, the capital of Latvia. They exemplify the artist’s longstanding dedication to making work with and about queer and underground communities in post-Soviet societies. Ever since he first picked up the camera, Zielony has created pictures of people who struggle to define their own representation and chose to show themselves to his camera, his gaze. His oeuvre is informed by a profound empathy; the way he allows human beings to appear promises dignity for all.

(3) Mario Pfeifer’s (DE) work has been focused on the Western Sahara region for over a decade; he is currently spending time on the scene to complete a large project. His photographs (Mirrored Dahkla (Camps), 2015) show areas that have been under Moroccan occupation in contravention of international law for 50 years; much of the indigenous population, meanwhile, lives in refugee camps in southern Algeria. Morocco has been systematically taking control of institutions, religious buildings, port facilities, industrial installations, and residential neighborhoods.

Vulnerable, 2024, exhibition view at KOW,

courtesy KOW, Berlin,

photo: Ladislav Zajac.

(4) The artists of the Congolese Plantation Workers Art League (CATPC, DRC) work through colonial experiences and a history of violence suffered over generations. Résis-tant déporté et incarcéré (Lumumba) (2022) shows the champion of African liberation movements Patrice Lumumba, who was elected the first prime minister of the independent Republic of the Congo in 1960. Only months later, he was executed at the instigation of the U.S. and especially of King Baudouin of Belgium.

(5) Santiago Sierra (ES) has printed the Kingdom of Spain’s coat of arms on paper (NATIONAL COAT OF ARMS OF SPAIN STAMPED WITH BLOOD, 2022). Instead of conventional pigments, he used donated blood from (all!) countries of the erstwhile colonial empire as well as formerly independent regions in the Iberian Peninsula. The blood stamps are small enough to fit on a passport page—a reminder of how often the establishment of nation-states has been accompanied by bloodshed.

(6, 7) A pioneer of gay self-representation in Brazil, Hudinilson Jr. (BR) was long upstaged by better-known colleagues. After his death in 2013, his work has begun to attract broader attention. It shows the bodies, the desires, the contradictions, and the masquerades of a queer underground world creating its own representations.

(9) Alice Creischer’s (DE) creative practice is vulnerable out of profound insight: committed to unflinching social analysis and economic critique, the artist has forged a precarious aesthetic that is alert to the open flanks of its own positions and aesthetic formulations. An Infamous Derangement of Eternity (2017) shows London’s banking district in 1748 and the production of homelessness (and death) by British colonial policies in India.

(10, 11, 12, 17) Peter Friedl (AT) is represented in the exhibition by works in pink from the early 1990s, a kid roe and two pictures. Meaning is inevitably fragile or precarious in Friedl’s oeuvre: his works are open to his own thinking and tightly insulated against thirdparty interpretive regimes. His silkscreen painting Untitled (Volontà) (1990) is based on an anthroposophical sketch, a choreographic notation describing eurythmic movements of the body meant to strengthen the will.

(13, 29, 30) Franz Erhard Walther’s (DE) oeuvre is represented by three historic Work Drawings (1971/72). These delicate creations on paper reflect on interpersonal and mental processes involved in the work on art as well as its contemplation—and in the world of social relations more generally. Rather than representing stable structures, Walther’s sketches are situational and contingent: open to future amendment. Blending rigor with playfulness, they catalogue human ideas and forms.

(14) The small painting by Anna Boghiguian (EG) we show (Untitled, 2010) is a portrait, perhaps a self-portrait; then again, “self” may not be a helpful concept in talking about Boghiguian’s art. What we are looking at may be an inner state of mind. Of someone. Perhaps of many someones. Boghiguian spent decades forming bonds with many people all over the world and telling the stories of their struggles and their losses.

Vulnerable, 2024, exhibition view at KOW,

courtesy KOW, Berlin,

photo: Ladislav Zajac.

Vulnerable, 2024, exhibition view at KOW,

courtesy KOW, Berlin, photo: Ladislav Zajac.

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2017, exhibition view ‘Vulnerable’ at KOW, Berlin, 2024, courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin, photo: Ladislav Zajac.

(19) Clegg & Guttman (IL/US) have arranged a simple experiment to test the audience’s tolerance for pain. They provide a candle and a lighter together with a simple instruction: the viewer is to hold their hand over the burning candle for as long as they can stand it. The small participatory sculpture comes from their work on video Follow the Rule (2019).

(20) Candice Breitz (ZA/DE) presents nine photographs from her project Whiteface (2022), which uses mordant satire to expose characteristic forms of the self-defense of white supremacy. Wearing a variety of blond wigs and donning zombie contact lenses, Breitz embodies a series of roles from white identity propaganda.

(21, 22, 23) Many works in Barbara Hammer’s (US) large oeuvre address the ways in which institutional medicine handles the female body—especially the body suffering from breast cancer, the illness that ultimately took the artist’s life. In the 1990s, she experimented with X-ray images of the thorax, overpainting the material—in 2016, she returned to the subject in an uncompromising film (A Horse Is Not a Metaphor, 2008) that grapples with her own battle with breast cancer in a heavily symbolic reflection.

(15, 16, 24, 25) Michael E. Smith (US) fashions a materiality of precarious basic needs. His works look like the oddments of a world of things abandoned by civilization that still bear the bruises of human use. Resting on the floor are half a Batman emblem shaped out of the withered stems of two pumpkins (Untitled, 2020) and 3-D prints based on CT scans of two dog torsos.

(26) On December 30, 2015, Turkish police attacked a peace march in Diyarbakır, sending hundreds of civilians fleeing. Among them, holding a running camera, was Pınar Öğrenci (TR). The film A New Year’s Eve (2021) documents the events and pays tribute to the Kurdish resistance to the violence perpetrated by the Turkish authorities. And it bears witness to the solidarity of a people who respond to tear gas with sugar.

Peter Friedl, Untitled (Volonta) 1990 (left), Untitled 1993 (middle), Untitled 1993 (right), exhibition view ‘Vulnerable’ at KOW, Berlin, 2024,

courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin,

photo: Ladislav Zajac.

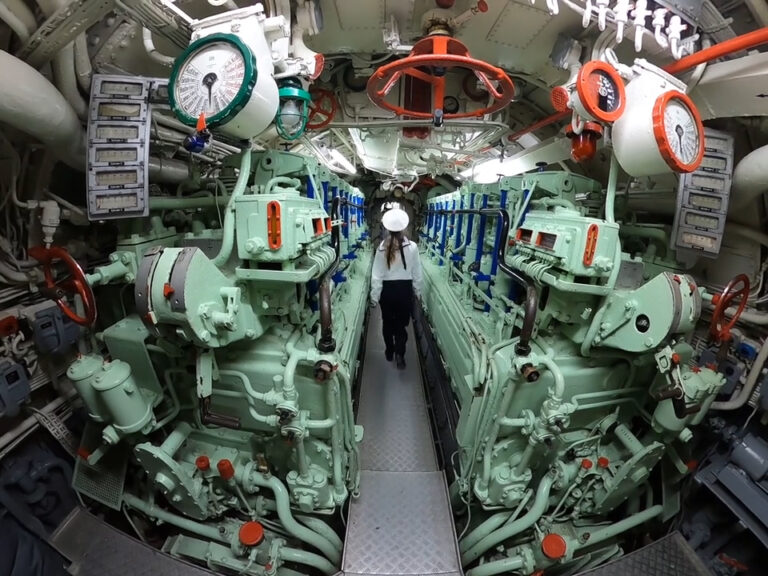

Sophia Eisenhut und Max Eulitz, Das Boot, 2024 (video still),

courtesy the artist.

Tobias Zielony, Angel, 2018 (left), Hair, 2018 (right), exhibition view ‘Vulnerable’ at KOW, Berlin, 2024, courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin, photo: Ladislav Zajac.

(27, 28) Selections from Simon Lehner’s (AT) widely noted photographic cycle Men Don’t Play (2015–19) are making their Berlin debut. The shots show young men who meet to dress up as soldiers and cosplay war, but where one might expect to see tough dudes, they capture a self-romanticizing community held together by sometimes tender intimacy. The hobby soldiers’ exercises are held every year in Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, or Austria.

(32) The soundtrack of Sophia Eisenhut’s and Max Eulitz‘ (DE) disconcerting tracking shot through a German submarine built in 1943 quotes from the notes of the medical officer candidate J.B., who served on board such a vessel from 1989 until 2008 (Das Boot, 2024). The unsettling testimony of a German soldier meets contemporary anxieties in the fraught military interior of German remembrance culture.

(33) From the collection of Ramon Haze, which gathers works from the past cultural epoch, we present Franz Erhard Walther’s two-part Mental Work (1982). Walther installed the two leather cushions above the urinals in the men’s room at Moschi Bar in Mönchengladbach to enable soused gentlemen to rest their foreheads against them while passing water. The work exemplifies Walther’s approach to making art objects that can be put to use.

(34) For León Ferrari (AR), the Catholic Church was a regime of violence that he often criticized and ridiculed in frankly blasphemous works. His small tank with Jesus (Untitled, ca. 2008) pinpoints the alliance between morality and military, between religion and war. Perhaps it also speaks to contemporary ambivalent feelings and controversies between pacifists and advocates of militarization?

(35) Anna Ehrenstein’s (AL/DE) most recent work Intimate Histories (2024) was created in collaboration with Rebecca Pokua Korang (DE) in response to how the “clan crime” myth is instrumentalized for political purposes. The original work of art—a car printed with writings and outfitted with a video projection that the artists parked in a street in Berlin— was towed as “propaganda.” We now present an installation that responds with a counternarrative against populist stories about large families and organized crime.

Hudinilson Jr., Untitled, 1980, (left), Untitled 1980/2009 (right), exhibition view ‘Vulnerable’ at KOW, Berlin, 2024,

courtesy the estate of Hudinilson Jr. and KOW, Berlin,

photo: Ladislav Zajac.

(36) Clemens von Wedemeyer’s (DE) early oeuvre is exemplified by a digital print (Current Cutter, 1999). Emerging from what feels like an otherworldly black pictorial space, the isolated human figure looks “scanned,” an effect we are now familiar with from various screening devices installed at airport security checkpoints and elsewhere. It is the visual language of surveillance technology that registers and recognizes bodies in order to turn them into objects of the law.

(37) In a growing series of charcoal drawings (Repository, 2024), Helena Uambembe (ZA) works through archival photographs of South Africa’s 32 Battalion, in which her father served. The photos show soldiers in the field, during parades, or on official occasions; many of the pictures circulate on social media, stripped of their context, the people in them turned into anonymous figures, mere ciphers. Charcoal in hand, Uambembe brings their stories and difficult lives back into the material world.

(38) Moon Calendar (2007) shows Hiwa K (IQ) inside the Red Security Building in northern Iraq, one of the notorious prisons in which Saddam Hussein’s regime had political prisoners incarcerated, tortured, and killed. The artist tap-dances to the beat of his own heart, to which he listens using a stethoscope, while his steps resound in the room. Synchronizing interior and exterior echoes of the horrors of the past, the work undertakes an acoustic mapping of remembrance.

(39) Heinrich Dunst’s (AT) art points up that representation does not add up: no meaning is stable; no proposition is itself. Titled Things, not Words (2016), the installation we present contains a pair of pants and a canvas. It is about the step or stride, the crotch or crutch, the cut that passes through things, bodies, and interpretations. Dunst’s oeuvre is traversed by an eminently contemporary experience: that nothing we see, say, and believe is solid.

(40) Dierk Schmidt’s (DE) genre is history painting—the big stories, unfurled on canvas. But his pictures tell counter-stories against the grand representation. The series McJob (1997) details the precarious, underpaid, and taboo wage labor that many artists rely on to make ends meet. The train car in this picture was sold by the German Federal Railway to a private buyer—Schmidt, the painter, was the gig worker who repainted it. Big business has its ways, but so does the informal economy.

Text: Alexander Koch

Translation: Gerrit Jackson