Venus und Sonne im zehnten Haus

Group show

Gallery Openings—15 Sep 2023, 6 to 9 PM

Wilhelmhallen

In the visual arts of the 1960s and 1970s, the serial and standardized procedures of Pop, Minimal, and Conceptual Art began to undermine the essentialist imperatives of originality and authenticity that had inspired artists and their works. This aesthetic strategy—and motif—of repetition is deeply anchored in the gallery’s program, with artists such as Charlotte Posenenske and Peter Roehr as well as Hans-Peter Feldmann and John Armleder.

“The repetition is the scene of a feminist instruction. A feminist instruction: if we start with our experiences of becoming feminists not only might we have another way of generating feminist ideas, but we might generate new ideas about feminism. Feminist ideas are what we come up with to make sense of what persists. We have to persist in or by coming up with feminist ideas. Already in this idea is a different idea about ideas.”

Sara Ahmed in living a feminist life, 2017

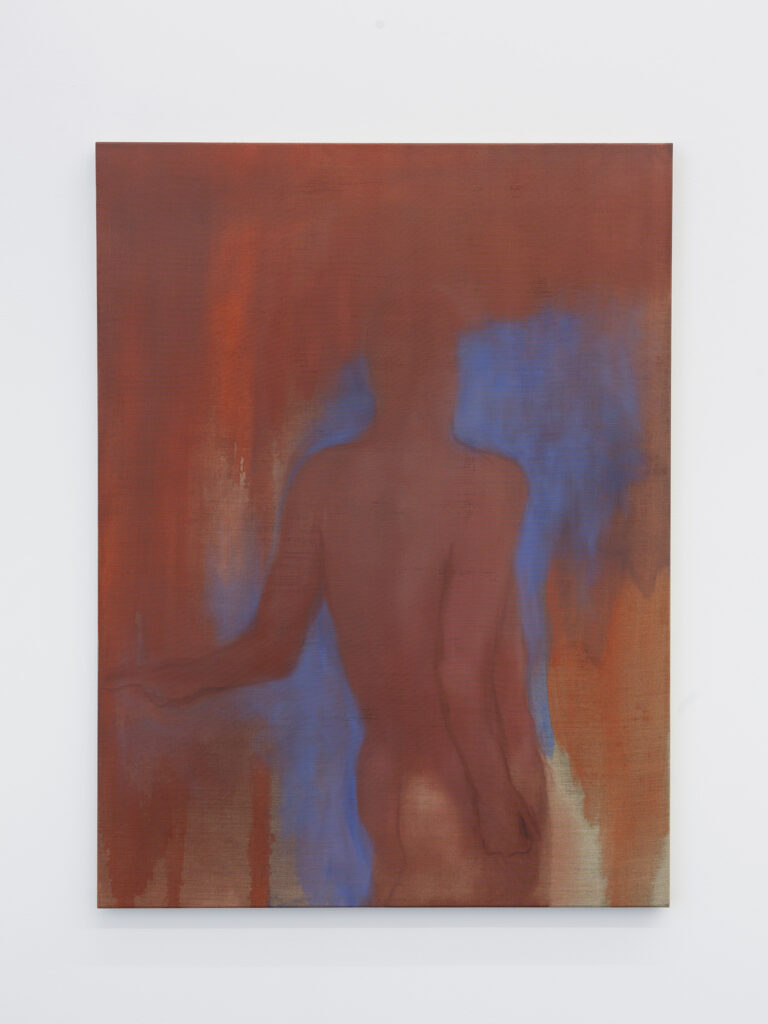

While the progressiveness of this concept by the neo avant-garde lay in the introduction of a neutral maker and viewer, in the context of contemporary identity politics, our understanding of subjectivity and objectivity has largely changed and diversified. British author and feminist activist Sara Ahmed describes repetition in this context as a “site of feminist instruction.” Ahmed thus emphasizes that feminist theory is not a static container, but a work in progress, anchored in everyday life and subject to constant repetitions, loops, and learning processes, as well as corrections, interruptions, and changes. With this as a starting point, the group exhibition Venus und Sonne im zehnten Haus brings together a range of contemporary artists using serial and standardized methods to contextualize their own artistic subjectivity within our material and polyphonic reality: between generations, cultures, subjectivities, and media. The ten artists gathered here—Julia Dubsky, Hannah Sophie Dunkelberg, Simone Fattal, Rochelle Feinstein, Estefanía Landesmann, Nancy Lupo, Liz Magor, Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, Margaret Raspé, and Marta Riniker-Radich—all engage with the artistic principle, aesthetic, and motif of repetition in their own individual ways.

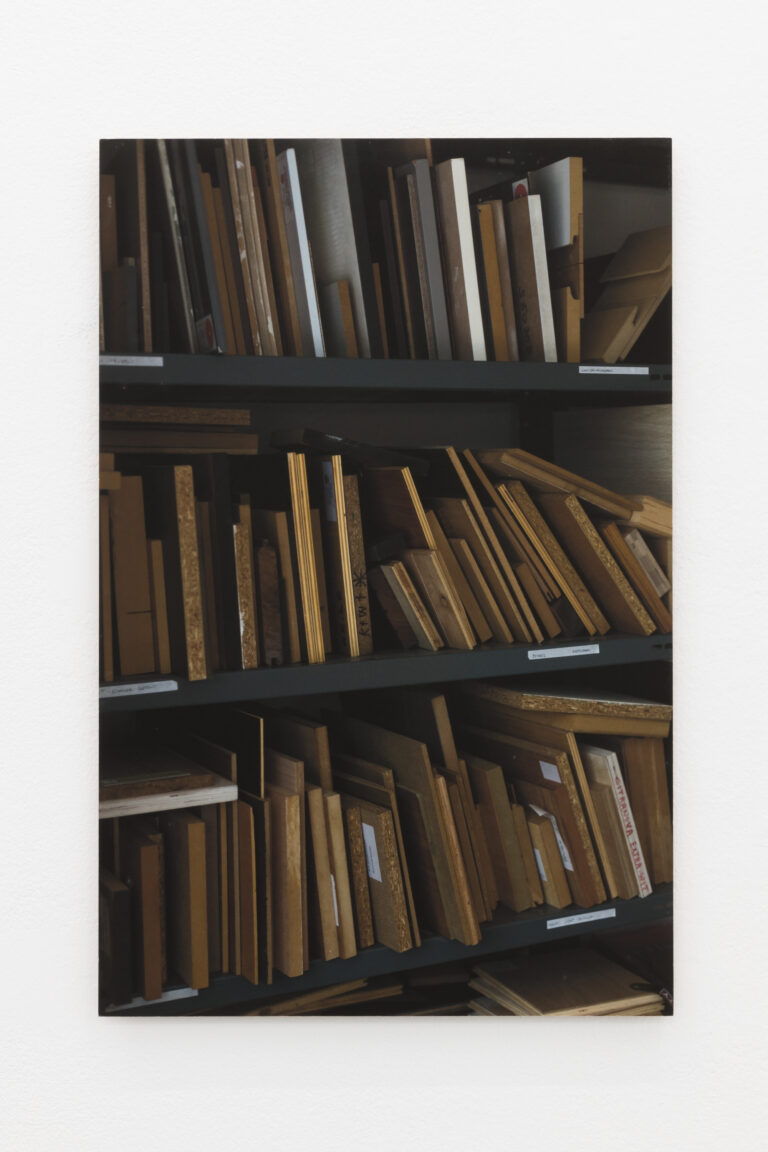

Archiv Charlotte Posenenske

Documentation and photographs of gallery exhibitions from the 1960s

KLEINE GALERIE | DOROTHEA LOEHR

KONRAD FISCHER | GALERIE H

ART & PROJECT | EDITION RENE BLOCK

Gallery Openings—15 Sep 2023, 6 to 9 PM

Archiv Charlotte Posenenske (Wilhelmhallen)

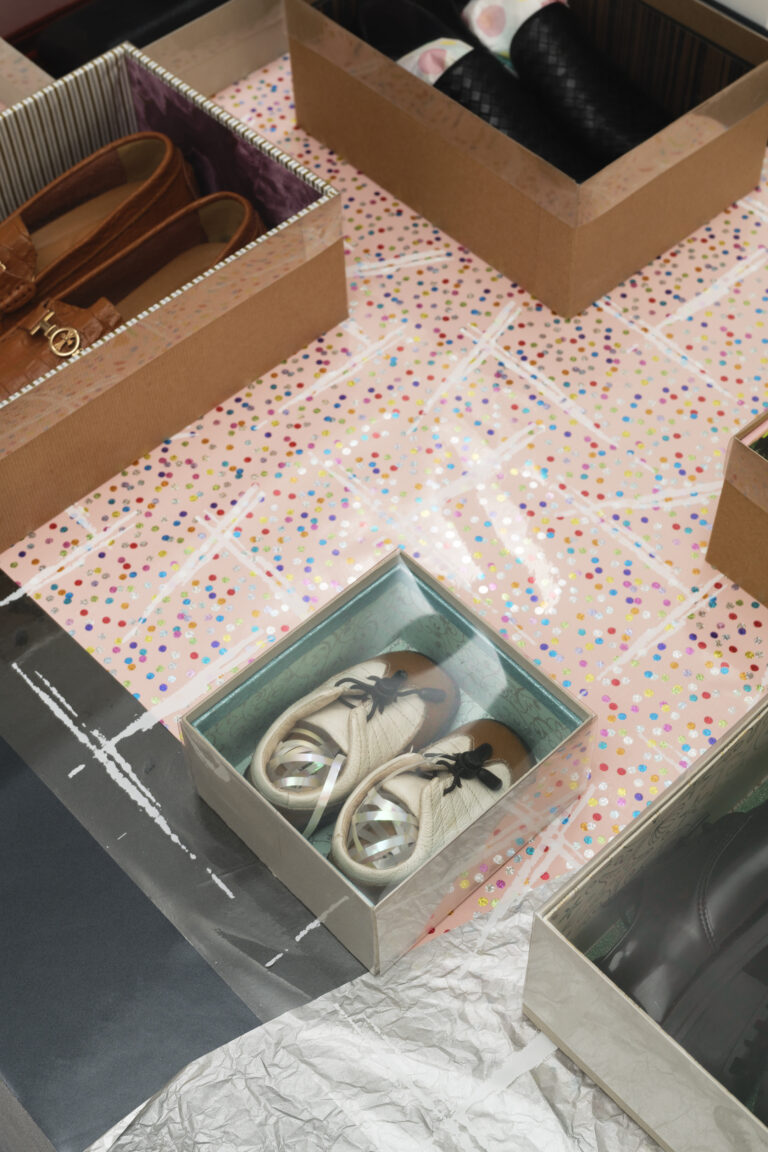

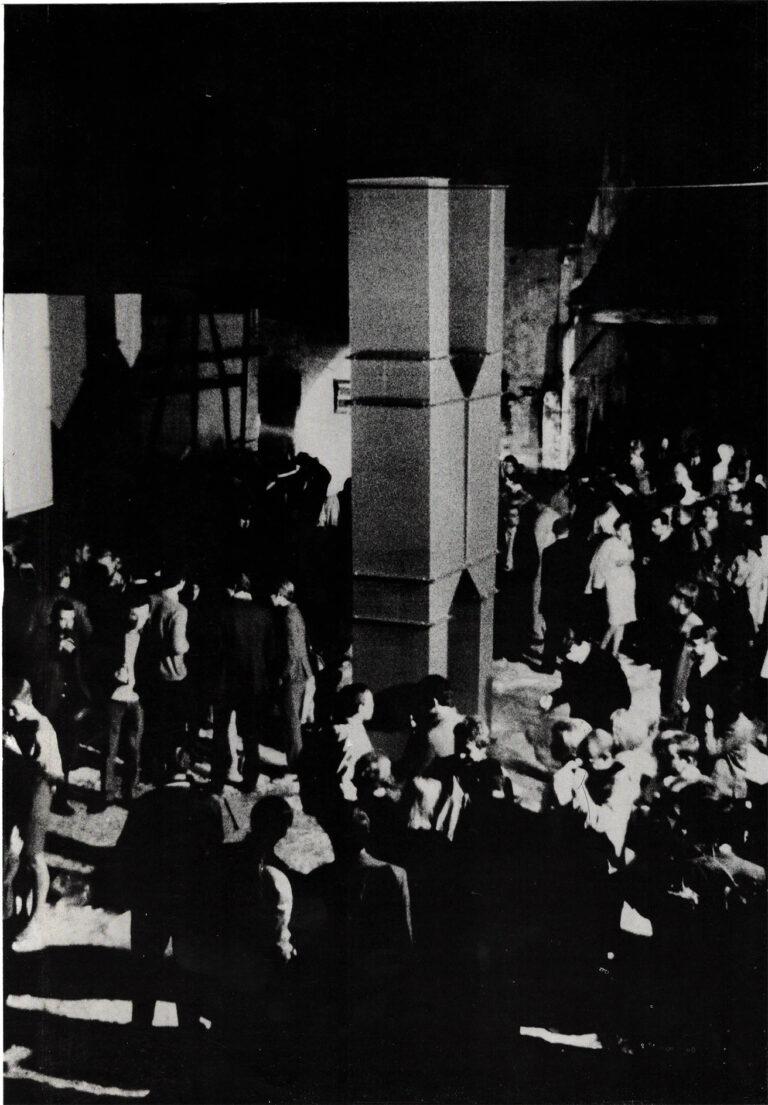

Installation View, Dies alles, Herzchen, wird einmal dir gehören, Galerie Dorothea Loehr, 1967

FOUR QUESTIONS TO PAUL MAENZ

Paul, during the 1960s, you lived in Frankfurt am Main and New York and actively participated in both locations’ art scenes, organising exhibitions and publishing editions. How was the gallery scene in Europe and New York back then, also compared to today?

Paul Maenz: That could be quite a long story, actually… While New York was an absolute art centre at that time, albeit purely American-focused, the gallery landscape in West Germany still resembled a giant patchwork quilt, with contemporary art struggling to find its way into the public eye. The press hardly mentioned it. Nonetheless, there were passionately run, engaged, forward-thinking, mostly smaller galleries nationwide. It was not until the unexpectedly great success of the newly created art fair “Kölner Kunstmarkt”, which served as a model for the future “Art Basel”, that Cologne emerged as a notable, internationally relevant gallery location.

After returning from New York in 1967, you met Charlotte Posenenske and immediately involved her in two important projects, including “Herzchen…” at Dorothea Loehr in Frankfurt. How did the Loehr Gallery in Frankfurt am Main operate at that time?

PM: Dorothea’s avant-garde gallery – one has to call it that because of its genuinely advanced programme – had experimental value. Always risking commercial success, Dorothea consistently showed the latest and most experimental works. Hence, it was an exciting platform also for Charlotte, whom I had met only a short time before, incidentally thanks to my friend, the artist Peter Roehr. Peter was a frequent, wellinformed conversation partner of Dorothea Loehr – so one thing led to another. It was an innovative and productive community that formed against the backdrop of those commercially meagre, less international Frankfurt years.

Posenenske occasionally asked you to help her with exhibitions, such as in Hanover and Gießen, writing texts or designing invitations. Was it common for galleries to hand over their introductions and invitations to third parties back then?

PM: Not really; it simply happened that way. Having worked as a designer and art director for an American advertising agency, it was not too difficult for me to visually present artistic concepts in a somewhat appealing and understandable way. Above all, it was a pleasure to work with artists, often in a very practical way – provided that the chemistry was right, of course, and our line of thought aligned. In terms of the content—the “actual” art—there were always fascinating learning processes, which, for example, in the case of Roehr or Posenenske, frequently resulted in quasi-joint practice.

Charlotte Posenenske ended her artistic practice in 1968 and withdrew as an artist, arguably against the background of political and social change in Western Europe. Was her decision also fuelled by the problematic reception of her work by the art market and the institutional setting, by a lack of recognition?

Charlotte publicly stated in her “farewell manifesto” that, as an artist, she was increasingly plagued by art’s “regressing social function” and its inability to “contribute to the solution of urgent social problems”. Far from being a political romantic, she hoped to find answers by studying sociology and in scholarship. Fortunately for us and the future of art, this did not stop Charlotte from standing by her work and guarding it – and, decades later, when she was already marked by an incurable illness, from agreeing to display it in a large exhibition in my former gallery in Cologne. Charlotte Posenenske did not live to see the opening on 11 December 1986. But I think she would have enjoyed this presentation with its expansive arrangement, created at the time with her husband, Burkhard Brunn.

Paul Maenz (b. 1939) ran a gallery in Cologne for art of the international avant-garde; he has lived in Berlin since 1992.