New Kids on the Block

A Wave of Young Galleries Bring a Fresh Energy to Gallery Weekend

Duncan Ballantyne-Way, MAR 2024

In the past few years, a handful of exciting, young(ish) galleries have forced their way onto the list of Gallery Weekend. Run by an array of international gallerists, their distinctive style and fresh perspectives have rejuvenated Berlin’s most prestigious contemporary art event. Galerie Molitor, Noah Klink Galerie, Schiefe Zähne, Sweetwater and Heidi are all at the forefront of a wave of young galleries, and their inclusion doesn’t just underscore the quality of the city’s commercial landscape but speaks to the overall vitality of the Berlin art scene. With their ability to amplify diverse voices and to find ways to respond quickly to the social, cultural and political contexts of our ever-changing world, these often more experimental galleries can play a pivotal role in appealing to new art audiences and to uncover artists who may have been overlooked.

That’s certainly the case with Galerie Molitor who, before opening, had already identified several unrepresented Berlin-based artists they wanted to work with. “We knew we could bring something new to the city’s vibrant scene,” Says Marie-Christine Molitor, who founded the gallery in 2022. In the short time Galerie Molitor has been around, it has put together a diverse, intergenerational program, mixing much-admired artists such as Margaret Raspé – who experienced a late career boost just before her death last year aged 90 – with younger, mid-career artists like Lisa Jo and Jesse Darling – last year’s winner of the Turner Prize. The gallery’s readiness to extend their exhibitions with poetry readings, performances and even a QiGong practice has been instrumental in raising its profile while reinforcing its conceptually driven program that “reflects on the contingency of making and exhibiting art.”

The right location can make a huge difference to the success of a young gallery, and Molitor ’s position on Kürfenstenstrasse, just a stone’s throw away from the cluster of established spaces orbiting around Potsdamerstraße, guarantees a constant stream of visitors. Directly opposite, Pauline Seguin founded her contemporary art gallery, Heidi. A former director of Gavin Brown Enterprise, Pauline, who had previously been based in Paris and New York, had been on the lookout for a good location when, in 2021, she stumbled across an “incredible space that was empty and neglected – only the challenge was to convince the owners to let us rent it.” Alongside a selection of hip, European and American artists, the gallery also works with more established positions, such as the legendary performance artist, Joan Jonas. “But describing the gallery’s program is a challenge,” says Pauline, “It’s about showing artworks and artists that resonate with you on a profound level, ones you passionately believe in and are willing to champion.”

Setting up an art gallery can be relatively easy. But maintaining it and turning it into a successful business is another matter. “The gallery profession is incredibly challenging,” says Pauline, “it requires a lot of perseverance and resilience to make it sustainable.” The effort has clearly paid off, with Heidi a fixture of major international art fairs (Paris+ par Art Basel and Frieze London) and attracting a trendy and discerning art crowd. For Pauline, “Curating exhibitions, participating in fairs, collaborating on projects we are really animated about, is fulfilling and very enjoyable.” That sentiment is echoed by the gallerist Noah Klink, who feeds off the energy that comes with “showcasing new exhibitions every six weeks, seeing fresh works adorn the walls and knowing it’s my work environment.”

Founded in 2017, Noah Klink Galerie is a short walk away from the respected art spaces of Schöneberg. Located in a former cafe, Noah was keen to translate that easy-going vibe to his gallery, to create “a bar environment conducive to bringing people together.” Far from being buttoned up affairs, his gallery openings are relaxed and convivial, with tables and chairs set up outside and children often seen hurtling around the exhibition space. That accessibility is vitally important; small galleries are at the core of the art world, uniquely enabling direct engagement with the local art scene. It is why the gallery aims to work with artists “at the early stages of their careers,” says Noah. “Fostering deep personal connections and giving them time for their individual practices to develop.” One of the standout artists on the gallery’s concise roster, is the young Berlin-born artist, Josefine Reisch. Showcasing her witty and deceptive deconstructions of European cultural heritage, Reisch has already completed three shows with Noah Klink.

The relative affordability of the German capital’s rental market compared with other European art metropolises like London or Paris, have traditionally made it a more appealing place for a fledgling gallery to start out. And with his strong network of friendships and connections, Noah, who grew up locally, never considered setting up his gallery anywhere else. The same could not be said for the former Los Angeles and New York resident, Lucas Casso, the founder of Sweetwater, who ultimately decided to set up his gallery in Berlin because the people are “smart, engaged, and critical and there’s no shortage of artists, curators, and writers.” He first opened his gallery in a large Altbau building on Kottbusser Damm in Kreuzberg, but when the “architecture began to feel a bit limiting,” moved the gallery to its current location on Leipziger Straße. Situated just around the corner from the Julia Stoschek Foundation, the new larger space, with its six-metre high, floor to ceiling windows, allows for more expansive installations – an important factor for an ambitious young gallery.

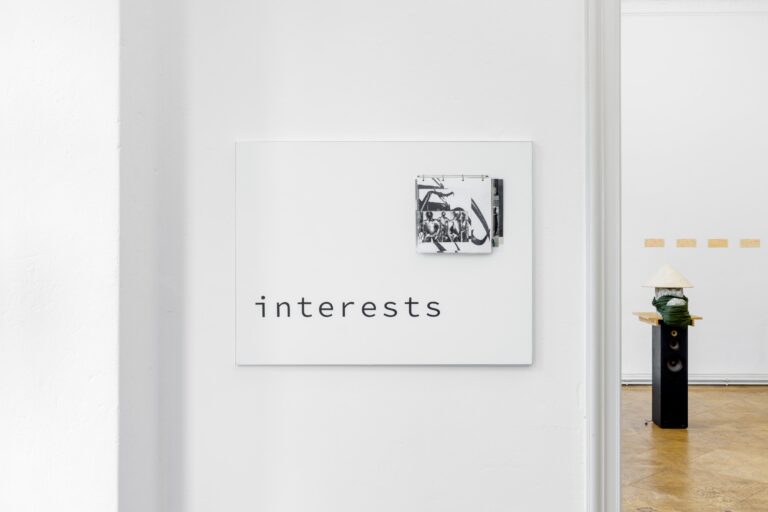

Sweetwater’s program is highly conceptual, with a strong international focus that balances a mix of European and American artists. Many of them work freely across different media, such as the young Los Angeles-based artist, Jesse Stecklow, whose clever, playful installations reveal the often-unseen interactions between people and their environment. “I really enjoy working with artists over long periods of time,” says Lucas, “the practices and programs both evolve and grow together, which is a rewarding process to be a part of.” Young galleries usually forge closer bonds with their artists, and that nurturing, supportive aspect typifies how many have come to regard Berlin’s art ecosystem, that allows artists to develop in their own time without imposing commercial pressure too early. Despite the difficulties of having to “paraphrase a gallery program in a few words,” Lucas, who formerly worked as an investment banker at Goldman Sachs in New York, believes it “reflects mainly on art, language, and commerce.”

The new galleries all demonstrate a shared commitment to engaging with contemporary societal issues through their socio-critical programs; what Pauline from Heidi gallery terms: “a compelling examination of our society”. And despite the diversity that exists between their programs, they are unified in the singularity of their visions. Allowing them to make choices based on intuition and conviction. It is one of the reasons why Molitor Galerie, a women-led gallery, finds themselves predominantly working with women artists: “This is not a hard rule of any kind,” Marie-Christine explains, “but rather reflects the artists we’re motivated to work with.” Their position reflects the re-evaluation going on throughout the art world; an ongoing process addressing deep-rooted gender imbalances and prejudices.

In younger and typically smaller galleries, the challenges faced are often exacerbated by more limited resources. “I could write an entire book about the administration and bureaucracy we deal with”, says Lucas, “but I’m not sure anyone would want to read it.” It is a grievance shared by nearly all the featured galleries, as they juggle tasks between small teams. For Molitor’s Marie-Christine, by far the greatest challenge is “the economic and political instability in which we are living and navigating how to do our work in this context”. That precarity often goes unseen amidst the cycle of sparkling new shows and social events. Yet despite the unpredictable nature of the industry and the ongoing demands they confront, none of the gallerists would ever dream of doing anything else. “Owning a gallery is wonderful,” says Heidi’s Pauline, “it’s a labour of love fuelled by passion.”

Duncan Ballantyne-Way