Base Matter

John Miller and his partner, the artist Aura Rosenberg, discuss his exhibition An Elixir of Immortality, on view at the Schinkel Pavillon until December 13th, 2020.

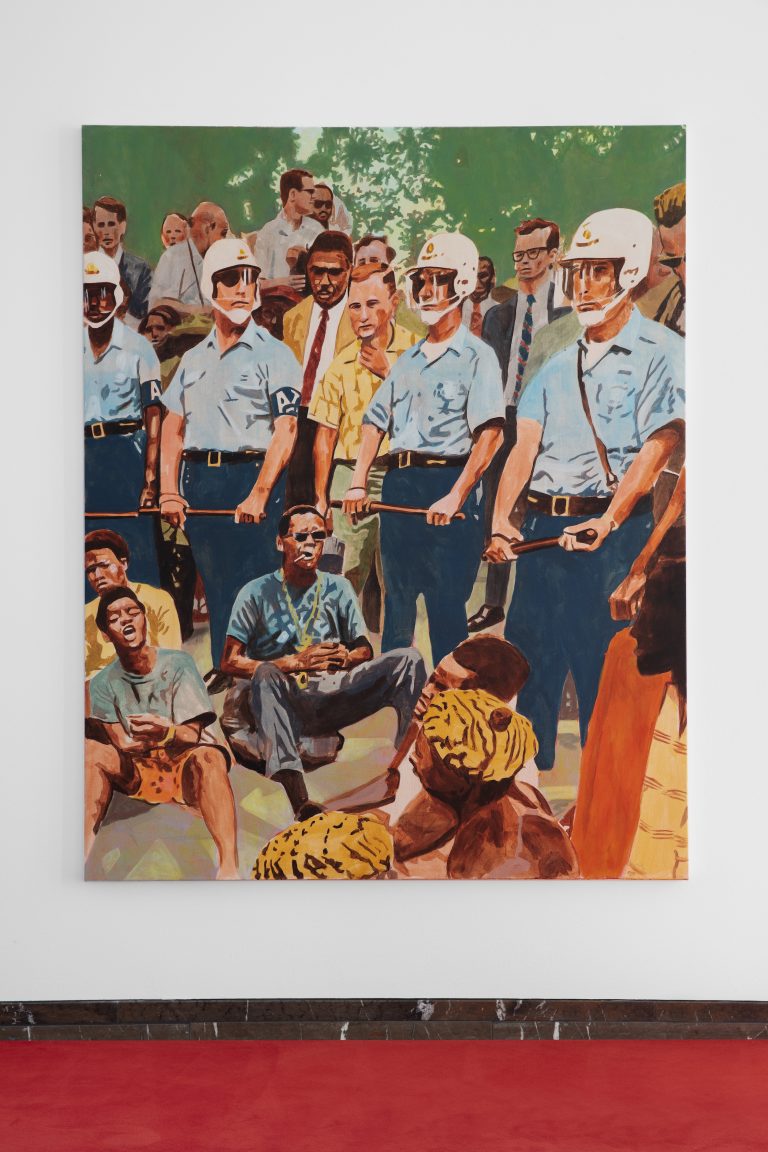

Installation view An Elixir of Immortality by John Miller.

Courtesy Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

Aura Rosenberg Why don’t we start off by talking about the title of your show An Elixir of Immortality.

John Miller It comes from alchemy, which promises an potion that supposedly can bestow eternal youth. I chose that title because turning base matter into gold is another goal of the alchemist. My show at the Schinkel Pavillion is organized with gold work on the upper level and brown work on the bottom. I thought transmutation could be an apt metaphor for the symbolic nature of the installation, one that plays off its specific architectural context.

What I hadn’t expected was how charged the notion of immortality would become. Since the pandemic struck, everyone must confront their mortality in unprecedented ways.

AR So, your title acquires a pertinence, a timeliness, because of COVID-19. But since you chose it before the pandemic, I’m wondering if it has personal relevance, that you’re getting older and thinking about your own mortality.

JM There’s no getting around the question of aging. And artworks intrinsically function as a temporal index. Vilém Flusser, for example, describes photography as a bid for immortality. According to him, since photographs are basically vessels for storing information, photographers memorialize themselves through this. I think the same can be said of painters and sculptors. Even though the facture may be different, they too inform their material. All these media forms evince some desire to be remembered or to have something that you thought or looked at be remembered.

When I titled my exhibition at the ICA in Miami “I Stand, I Fall,” the curator Alex Gartenfeld observed that the condition of standing or falling can reflect the anxieties that retrospective shows bring up for many artists, like whether they’ll be locked into a signature style, whether their work will go downhill after that, whether they’ll get a second chance, etc. So, you do have to ask yourself what it means to have your life’s work summed up by an institution.

It’s also funny because up until now, the survey shows I’ve had been described as “mid-career retrospectives.” But now that I’m 66, if this were a mid-career retrospective, that would mean I’d be expecting to live to the age of 132.

AR That’s like a biblical age.

JM And with it, a sense of mortality hovers over your accomplishments!

AR As you say, it’s true for all artists. But, maybe it applies more broadly to all human accomplishments. Perhaps people make them in the hope of being remembered — as a kind of stand-in for their physical presence. Artists leave behind artifacts – an elixir of immortality.

JM Artists make works that have a representative function. So, these works are inherently charged. Because a retrospective brings together pieces from many different sources, you also confront the materiality of artworks. There’s an entropy to the social practice of collecting. Depending on who owns what, not everything is kept in ideal condition. And sometimes you can’t find the works you’re looking for because they’ve been lost, or because someone who’s collected the works has passed away, or if they have heirs, perhaps the heirs don’t care so much about art. Fortunately, I didn’t face such issues in this show.

AR It’s as though the works have a life of their own.

JM You could say, “lifespan.” Robert Smithson inveighed against the idea of “the timeless work of art.” Even though this phrase is typically meant as a compliment, Smithson took it to be an insult. He argued that it robbed the artwork of its temporality and the labor that the artist put into doing it.

AR Are we really in a position to determine that something is timeless? We won’t be here to evaluate it, we don’t know what’s going to survive and what’s not going to survive. That brings up another interesting aspect of your installation. Unlike any other exhibition you’ve done before, there are windows. The windows look out on buildings and ruins that project a vivid historical consciousness. There’s a real relationship between your installation and what we see outside. The other day, someone noticed that your golden ruins were reflecting in one of the windows. They almost seemed to be part of the outside architecture.

JM The work you’re referring to is a fake, large-scale ruin called “Mourning for a World of Rubbish.” Ironically, because it’s the newest work in the show, it hasn’t suffered any perceptible degradation! It’s leaved in imitation gold and set upon a red carpet in the upper level, in an octagonal room with large, floor-to-ceiling windows. This room is by no means a quintessential white cube; its unusual shape gives it a special theatrical quality, something like “theater in the round.” Even though I had gone there several times before planning the installation, I didn’t consider the simple fact that these picture windows create an immediate dialogue between inside and outside. My ruin further conflates interior and exterior space, a bit like an arcade or shopping mall, namely the kinds of commercial environments meant to naturalize the commodity fetish. I think this is because creating an inside world that appears to be outside produces a reflexive set of relationships that bracket how we attribute value to things.

When you look out the windows and what do you see? You see history, but you also see representations of history. I think that’s what’s going on with the new Schloss, which replaced the East German Palast der Republik. These different architectures reflect contested versions of history.

AR Your ruin references the large granite bowl in front of Altes Museum.

JM As a quasi-site-specific gesture, we produced what looks like a fragment of that bowl. Later, I learned that the bowl I referenced had in turn been inspired by the Emperor Nero’s so-called Golden Bowl.

AR For the past 30 years, we’ve spent about four months every summer in Berlin. This year because of the virus, we are meeting friends outdoors at picnics. One of our favorite places to have a picnic is on the lawn in front of that bowl. So, that relationship has become unexpectedly personal. Do you ever think about that, I wonder?

JM It’s funny that we’ve ended up hanging out so much around the bowl. We’ve entered into a relationship to it and the surrounding architecture that’s much different from sightseeing. Remember when our friend Nic Guagnini first came to Berlin and how he saw the local culture through the lens of classicism? Especially how the collective experience of being outdoors corresponds to a cult of nature. Maybe he witnessed the nude sunbathers in the Tiergarten! Of course, neo-classicism dominates the buildings on Unter den Linden. But you see that in American architecture too, with Federal architecture and Greek Revival, this invocation of Greek democracy. I think that’s what the architecture’s supposed to do. But it takes on a different inflection here.

In the last documenta, Adam Szymczyk raised questions like these, citing an exchange between Greece and Germany that entails specific aesthetic philosophies, such as those of Winkelmann. I like his approach because it considered neo-classicism from the standpoint of ideology.

AR Do you think spending so much time in Berlin, really having Berlin as a second home, might have been an influence then on this work?

JM Certainly! And not just the ruin, but also how my artistic career unfolded from early on. My work was accepted in Germany before it was in America. Part of the reason was that my early work used a scatological, brown impasto trope that Americans initially didn’t want to deal with. The culture in the United States largely derives from its puritan heritage. And it was much more puritanical in the 1980s than it is now.

AR But you started showing work in New York — before we came to Berlin.

JM Yeah, I started in New York, but shortly after, I showed the same or similar work in Cologne. The difference in the reception was pronounced. Although it was just brown acrylic paint, some American viewers told me that they couldn’t stand to look at it and that it made them queasy. Germans considered it more as an intellectual proposition; this generated a dialogue that proved to be quite important to me.