Rebecca Horn

Bee’s Planetary Map

Rebecca Horn, Bees Planetary Map, 1998. Installation view, Centre Pompidou-Metz, 2019, Photo: Jacqueline Trichard. © Rebecca Horn, VG Bildkunst, Bonn, 2021

Courtesy die Künstlerin und Galerie Thomas Schulte

On the occasion of this year’s Gallery Weekend Berlin, Galerie Thomas Schulte is pleased to present a solo exhibition by Rebecca Horn.

Thomas Schulte’s very first exhibition at the time of the gallery’s inauguration in 1991, featured Rebecca Horn’s installation Chor der Heuschrecken. 30 years on and many joint projects later, the gallery celebrates its 30th anniversary with an exhibition of one of Germany’s most important living female artists. Alongside Horn’s recent works, the gallery will be showing two of the artist’ seminal kinetic installations from the 1990’s: Bee’s Planetary Map (1998) and Der Turm der Namenlosen (1994).

In 1991 Rebecca Horn created her work Chor der Heuschrecken I,II for Galerie Thomas Schulte. This was the first time a sculptural choreography connected two spaces – and later, two places – in a landscape-like manner. This approach would also become form-defining for Horn’s work. So too would the insect: negotiating liminal positions between life and death with its spatial sensors and seismographic perception.

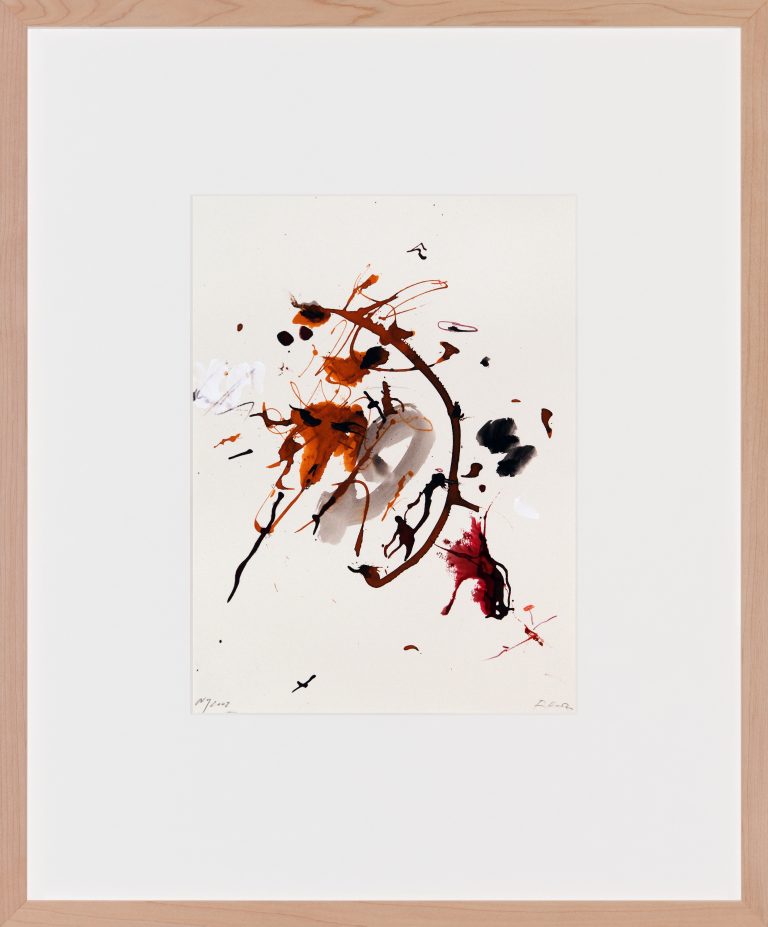

Rebecca Horn, Die Neuerscheinung, 2019. Courtesy the artist and the gallery.

1/4

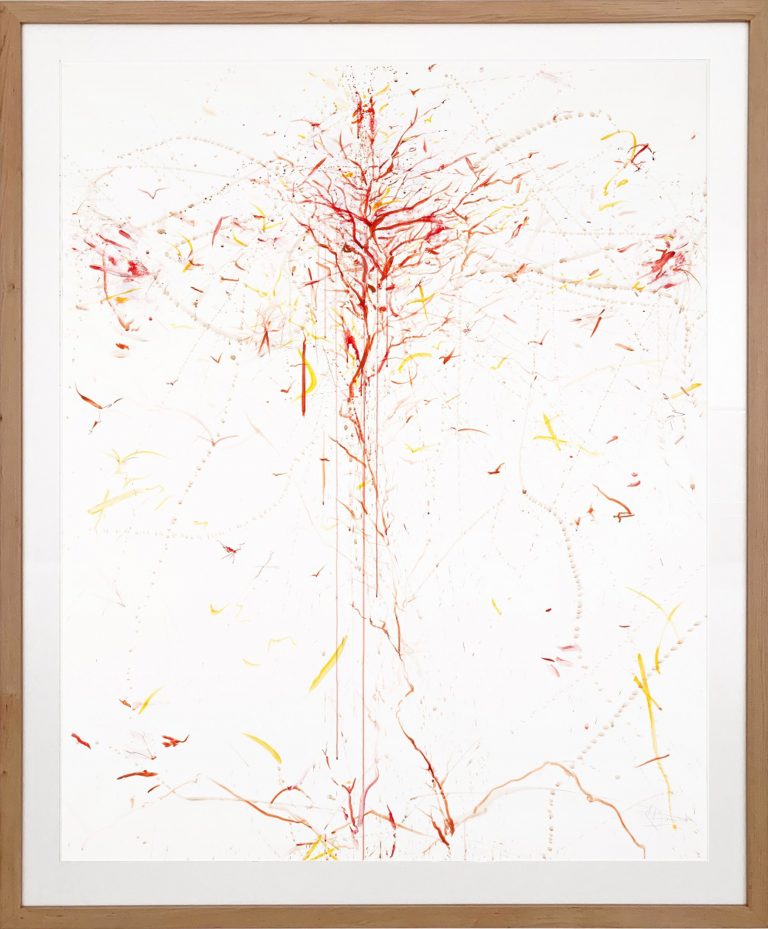

Rebecca Horn, Zimbel Zen, 2006. Courtesy the artist and the gallery.

1/2

We find this leitmotif in Bee’s Planetary Map (1998). The piece, at once site-specific, and yet not bound to any one space, captures the transformative power of bees: converting and repurposing natural substances to construct their habitats. Conceived in 1997, even before the flows of forcibly displaced millions from the Balkans, Bee’s Planetary Map captures themes of dislocation, uprootedness, and fractured movement. Empty beehives fill the space with the haunting buzz of a wandering swarm of bees. Honey-yellow light streams from the suspended baskets, which is in turn reflected off of circular, rotating mirrors and projected across walls and ceilings. At regular intervals of two and a half minutes, a stone attached to a mechanical hoist falls from the ceiling and shatters one of the mirrors. Spinning splinters of mirror chase panicked scraps of light across the room. Struggling towards the center, searching for protection and security, fearing for freedom and belonging – these are the central human themes in Rebecca Horn’s work.

Themes of flight and (up)rootedness are further visible in Der Turm der Namenlosen (1994). Rebecca Horn dedicated this piece to the thousands of, largely Bosnian, refugees who arrived in Vienna in the early-to-mid 1990’s. Most arrived without passports and without knowledge of the dominant language. Many would use the musical instruments they brought with them to express and perform their trauma.

Rebecca Horn, Chor der Heuschrecken, 1991. Installation view, Galerie Thomas Schulte, 1991. © Rebecca Horn, VG Bildkunst, Bonn, 2021. Courtesy die Künstlerin und Galerie Thomas Schulte

As if trying to escape from the window arches, a spiral of interlocking fruit-picking ladders crowd upwards toward the ceiling of the gallery’s nine meter high Corner Space. Seeming to climb the ladders’ rungs, nine violins begin to play a wild polyphony at regular intervals of three and a half minutes. The symbolic power of musical instruments – and the string instrument in particular – in contexts of trauma and displacement, has become a central leitmotif in Horn’s work. This is particularly true for her piece, Concert for Buchenwald. Created around the same time as Bee’s Planetary Map, this sculptural composition has been permanently installed in Weimar since 1999. A further leitmotif object in Horn’s work are the spinning binoculars which recur in her ten-part filmography including Der Eintänzer, La Ferdinanda, and Buster’s Bedroom.

Beginning with her early performances and now encompassing drawings, poems, overpainted photographs, stage sets, and paintings as well as her animated sculptures, Rebecca Horn’s oeuvre is continuously formed and reformed by intersecting and mutually reinforcing creative impulses and directions of inquiry. A centerpiece of her extensive oeuvre is her 1970 performance piece, Unicorn. A female figure extended by a rod; a vertical presence wandering the room, taking measure of the space. It is through her poetic imagination that Rebecca Horn obscures and stretches the figure into infinite depths and heights. In a similar way, the body becomes a central tool in her artistic creation; often measuring the large papers on which she draws according to the length of her arms. Pencil-marked focal points in her paintings, correspond to her own body’s center, and often remain visible in the final piece. In works such as Im Schatten des Schmerzes, meanwhile, the lower edge of the painting often takes shape through the implied silhouette of a landscape. Receiving their momentum from this line, streams of energy rise into the air, branch out gradually, and finally condense in a celestial space where they begin to swirl in an ecstatic, rotating dance. Their ascent to this spiritual height, however, is the product of a struggle between gliding, dark and light figures. As viewers, we become unknowing participants; physically imitating the upward and downward movements as we observe the figures’ struggle. As is true for most of Rebecca Horn’s work, the viewer is always implicated in the depiction.

Portrait von Rebecca Horn © Ute Perrey. © Rebecca Horn, VG Bildkunst, Bonn, 2021. Courtesy die Künstlerin und Galerie Thomas Schulte

Rebecca Horn (b.1944, Michelstadt, Germany) studied in Hamburg and London and from 1989 taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades. In 1972, she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Awards include: Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Alexej von Jawlensky-Preis Wiesbaden (2007), Alice Salomon Poetik Preis, Berlin (2009), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). A first mid-career retrospective of Horn’s work was organized in 1993 by the Guggenheim Museum, New York. It was the museum’s first solo exhibition dedicated to a female artist. The exhibition traveled to the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Nationalgalerie Berlin, Kunsthalle Wien, Tate Gallery and Serpentine Gallery in London, and the Musée de Grenoble. A second retrospective was presented at the Hayward Gallery in London in 2005. Another retrospective took place at Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin in 2006. In 2019, two major exhibitions of her work took place simultaneously at Centre Pompidou-Metz and at Museum Tinguely in Basel. The artist lives and works in Bad König im Odenwald.