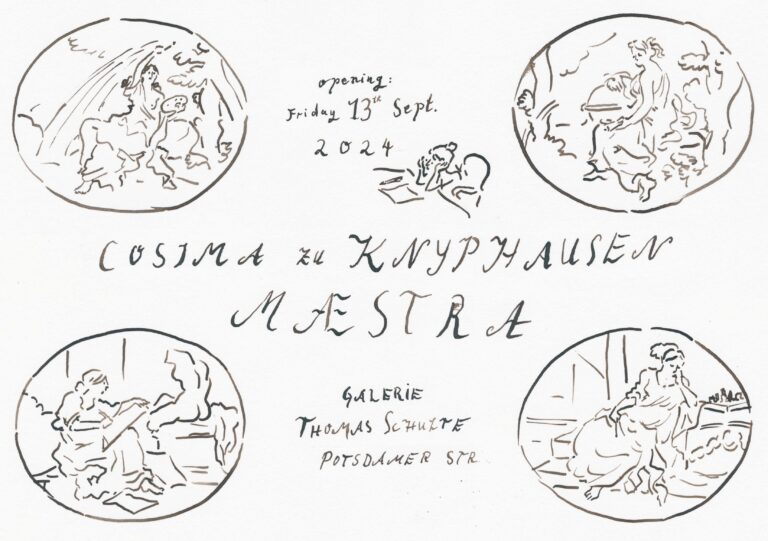

Cosima zu Knyphausen

Maestra

Opening – 13 SEP 2024, 6 to 10 pm

For the inaugural show in the new space at Mercator Höfe on Potsdamer Straße, Galerie Thomas Schulte presents a solo exhibition of recent paintings and drawings by Cosima zu Knyphausen. Through varied techniques, formats and materials, zu Knyphausen draws on sources from the art historical, literary and pop cultural to the everyday, personal and self-referential. The works brought together here under the title of Maestra trace fragmentary paths to learning and discovery across different realms of education and desire. What opens up is a layered reflection: on historical representations of women, as artists and in art; and the vocation of artist, its current models and canons, through the lens of her own artistic training and practice.

Whether contoured in loosely sketched, yet bold lines or taking shape through blurred atmospheres of vibrant colors in diffuse strokes, zu Knyphausen’s works invite us to draw close, as though peering into a book. In scenes frequently set in interiors, this impression is amplified by depictions and enactments of contemplation, analysis, reading, interpretation and reinterpretation.

A drawing offering a prelude, an invitation to the exhibition – which fittingly takes place down the street from the former site of a historic painting school for female artists1 – depicts the allegorical ‘Elements of Art’: Design, Composition, Coloring and Invention. Here, zu Knyphausen looks to the motif realized in the room-framing ceiling paintings of Angelika Kauffmann from 1778-80, which notably featured female figures in all four images. As representations of intellectual and creative activity considered fundamental to art, they also reflect the disciplinary pillars through which systems of organizing and categorizing it have been upheld. This referential quality, evident not only in the quoting of another artist, but also in the portrayal of the artistic process itself, is a thread that runs through. Titles of works like Ibídem (2023) and La Source (2024) – both of which show women in intimate pairings or groups as they pore over books or images together – even call on systems of citation embedded in the material of study. These, in turn, point to a certain place: to a beginning.

Among recurrent subjects like the artist’s studio or the revisiting of works by historical figures like Artemisia Gentileschi, there are allusions to zu Knyphausen’s own education – a kind of beginning: from attending an all-girls Catholic school to studying painting at art school. The latter at times appears in lighthearted, discrete references to the scathing mark left by an authoritarian professor. The figure of the professor is present and repeated in different works – In Boden der HGB (dreckig) (2022/23), for example, she stands at the end of a corridor facing a window, almost a shadow. What gives definition to the scene, however, is the black-and-white tiling of the art school’s floor. A moment framed by place, the pattern is not only reproduced in the small image at the center of the canvas, but is also blown up around it, extending to its edges. It could continue on, or perhaps open up to reveal something else entirely.

Such works – in which an image substantially smaller than the canvas is framed by, or layered with, an abstract pattern – often recall medieval miniatures and motifs. While the image fills more of the surface in other paintings, it is at times also vividly outlined, or contained within a rough oval, like a thought bubble illustrating a daydream. And still others comprise multiple scenes placed side by side, or stacked on top of one another, similar to a comic strip. Throughout, presented as vignettes, their pictorial framing is clear.

Further themes related to role models, complicity, and lesbian desire crop up. From snippets of a music video by t.A.T.u (“All The Things She Said” from 2002), framed by the motif of a chain-link fence; to a playful inversion of Death and the Maiden (2024), in which a naked figure stands confidently before a bed, presenting herself to the reclining skeleton of a lover; or a hazy scene in the interior of Möbel Olfe, a beloved queer bar in Berlin. Individual moments big and small, profound and mundane, fictional and real, across time and space, here occupy the same plane.

This fragmentary, patchwork approach is also reflected in zu Knyphausen’s use of materials that have been left over or produced through her time and work in the studio. These include more explicit references to painting production, such as strips of canvas and used staples, as well as more metaphorical ones, like egg shells. How difficult can it be (2024), for example, comprises a spattering of loosened staples on a dark teal background with a rugged piece of canvas applied to the center. In it, a small image in succinct black outlines shows an artist engaged in building a stretcher frame. While the egg shells similarly lend themselves to textured surfaces, they are also used for more elaborate, irregular patterns of tiling, like mosaics. In Egg Mosaic VI (2024), the broken shells are assembled, from randomness, into a specific grid: a chessboard. Left open and blank, it holds the potential for actions both planned and unpredictable. It offers a framework: for the configuration of different parts, rules, roles, strategies and relations; for a kind of world-building.

In Maestra, we are invited to contemplate our notions of trajectories to be followed, sets of rules to be mastered, and what is taught, learned, and often left out of such structures. More than an attempt to accumulate knowledge, achievements, or recognition; through continuous repetitions, reworkings and reimaginings, it is the desire to understand, (un)learn, create and transform, that is conveyed. A desire to seek out new narratives and representational possibilities, to pick up the pieces and build the frame anew.

1 Founded in the late 19th century, the first painting school to offer training to female artists in Germany, before they were allowed to study in art academies,was located at Potsdamer Straße 98.

Allan McCollum

The World: A Moment in Time

Opening – 11 SEP 2024, 6 to 9 pm

Charlottenstrasse 24, 10117 Berlin

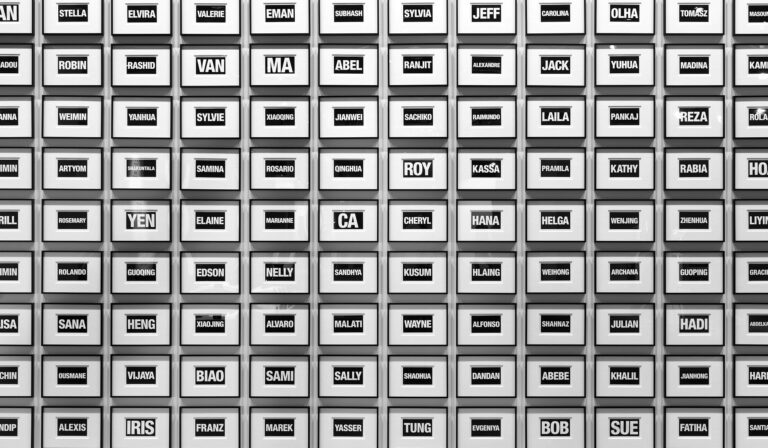

Allan McCollum, The World: A Moment in Time, Courtesy the artists and Galerie Thomas Schulte

With The World: A Moment in Time (2024), Allan McCollum revisits his sweeping, poignant installation Each and Every One of You (2004) – marking the occasion of the work’s 20th anniversary. Presented by Galerie Thomas Schulte for the first time in Germany, the new work takes a more expansive view, adapting to shifts in the geo-political landscape and societal discourses of the two decades since its initial conception.

Like its predecessor, The World: A Moment in Time comprises 1200 framed digital prints, each containing a different given name. It departs from the first iteration, however, in two significant ways. For the original work, McCollum drew on data from the U.S. Census Bureau, compiling names commonly used in the country at the time and breaking them up according to the 600 most popular female names and the 600 most popular male names. In contrast, the new work is a collection of the most common names worldwide and forgoes distinctions based on gender – resultantly absent of binary classifications or any other breakdown into discrete categories. Within this constellation, the prominent occurrence of names, for example, of Chinese, Hispanic, Indian, or Muslim origin, also visualizes current demographic statistics. In updating the work in this way, McCollum reflects on its place in an increasingly global society, while considering topics of inclusivity within the contemporary art context in which it is situated – and beyond.

The prints are identically formatted and hung closely together in a panoramic whole. Side by side, row by row, they form a dense grid that consumes the display architecture almost entirely. The shapes of white letters outlined against a black background – as though emptied out or still to be filled in – are strung together in a broad tapestry. Incessant regularity and sober order make this accumulation of objects appear at once overwhelming and highly controlled. But there are evident distinctions: scaled to fit the same image size, shorter names are made up of larger letters, highlighting changes from frame to frame and generating a certain rhythm. The white mats around them also keep them insulated inside of their autonomous black frames – marking a clear separation. Every single one is the same and yet each is its own.

The sense of intimacy afforded by the small size of the prints is curtailed by the distance and impersonal nature of the work’s scale and mass-produced sameness. And yet – although a name’s appearance in the installation is an indication that it is not unique – individuality is underscored by virtue of the singular presence of a name within this vast sea of many others, at the same time as possibilities for finding connection are opened up.

There is a collective emotional investment in the act of giving names. Maybe we grow attached to something only after we have named it; we give ourselves names that fit our identities; or we share a name with those we are connected to. In the space of this installation, perhaps we instinctively seek out our own names or those of friends and family – like rummaging through collections of personalized knick-knacks at a souvenir shop. In their straight-forward manner, the prints also resemble name cards or tags, for example, used for attendees and participants of a large-scale event. They could be markers for people who aren’t there: those who haven’t yet arrived or else have already departed. In their pared down black-and-white simplicity, we might sense a certain somberness – like standing before a monument on which a list of names have been etched in remembrance – or find ourselves flooded with personal memories and associations, like opening an old address book.

Beyond offering portraits of individuals, it is the emblematic nature of the names assembled here that contributes to a portrait of a particular moment. The title of the new work, The World: A Moment in Time, puts an emphasis on its own transience, even as it indicates a totalizing view. Through simultaneous modes of inclusion and reduction, it is a tangible imagining of the sheer scope of something that is otherwise difficult to conceive of. What we are presented with is a sort of abstraction of the world, a snapshot that we are invited to enter into – or are likely already a part of. It may represent a specific moment, already passed, but its potential iterations are without end, continuously unfolding through our individual and collective encounters.

Text by Julianne Cordray

Rebecca Horn

Concert of Sighs

Opening – 11 SEP 2024, 6 to 9 pm

Charlottenstrasse 24, 10117 Berlin

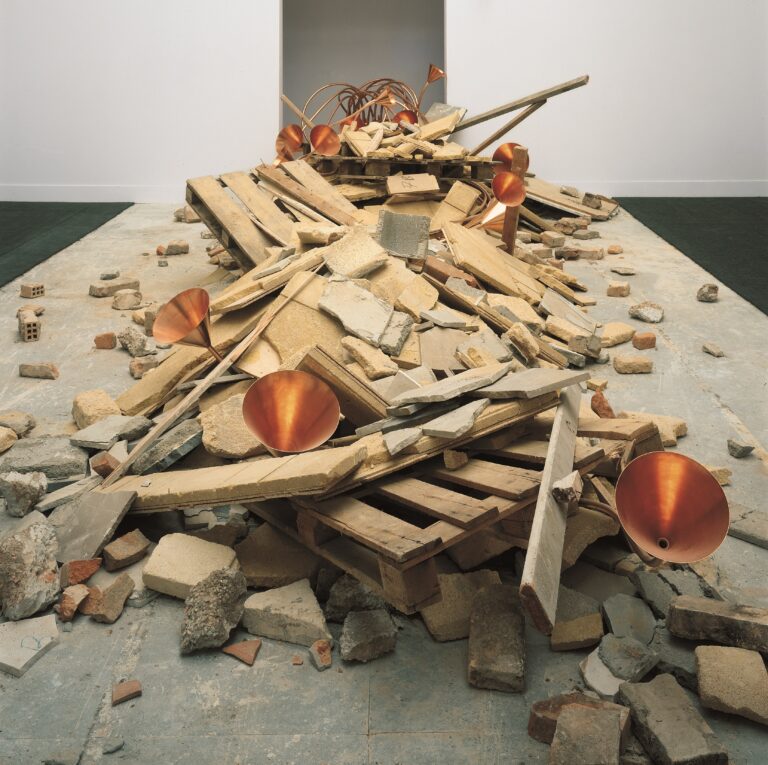

Rebecca Horn, Installation view, Courtesy the artist and Galerie Thomas Schulte

Rebecca Horn’s “Concert of Sighs” fills the space of Galerie Thomas Schulte, with the echoes muted whispers, which emanate from coiled copper trumpets jutting out of rubble. Piled on the floor are building pallets, wall fragments, and wooden boards, lay strewn in piles on the floor from which thin copper tubes wind like plant shoots, ending in funnel-like trumpet mouths. The artist used building materials from the ruins of Venetian houses for her installation, which was originally created for the 1997 Venice Biennale. Whispers and sighs seep through the individual funnel trumpets, as if offering a mouthpiece to the life beneath the ruins, or as if the crumbling walls of Venice were telling us their story. These delicate, yet haunting sounds, make the skin crawl, as the voices, audible in several languages, lament their suffering. As viewers, we do not merely hear the “concert of sighs”, we feel it as a physical and visceral experience. This work serves as a further testament to Horn’s mastery of sensory orchestrating: enveloping all our senses from balance to touch as the echoing sighs seep through our skin.

As we stand closer to the work, we feel its innate fragility; fearing that at any moment, a piece could fall, slip, and crush the copper pipes from which the sounds flow. Through our sense of balance, our bodies resonate with Rebecca Horn’s installation. On the one hand, we embark on a journey to Venice; on the other, we are confronted with a more wholistic sense of chaos and destruction.

Thus, it is its inherent multisensory power that makes the “Concert of Sighs” so significant. The work challenges our sense of balance, the solidness of the ground beneath our feet, and indeed, our sense of existential security. For Rebecca Horn, the body becomes a sensory commune in which the sense of touch – not sight – is the starting point and basis of a multisensory experience. The artist understands that touch encompasses the entire body and thus interacts with our other senses. We do not literally have to touch her works to see them embodied. It is a physically and emotionally activated perception that involves not only the touch of the hand, but the entire repertoire of the body’s materiality and its somatosensory experiences. It also draws on our depth sensitivity, pushing us to consider the position and dynamics of our bodies in space.

As recent research in neuroaesthetics shows, hearing is also a specialized form of tactile perception that is limited to a specific area of the body. In this way, we learn and take in information through each sensory experience, which goes beyond our cognitive or psychological forms of knowledge production. When we listen to the sighs, when we see and feel the elements of the dilapidated Venetian houses, we gain an embodied wisdom and experience that the artist is sharing with us. One which transports us beyond the decays of Venice, but which confronts us with our own contemporary world, regardless of the city we live in. This stands in contrast to Marco Polo’s character in Italo Calvino’s novel “The Invisible Cities”, who – no matter what city he was talking about – always told the story of Venice. What Rebecca Horn and Marco Polo have in common, on the other hand, is aptly stated by the Great Khan in Calvino’s same novel: “Admit what you are smuggling: states of mind, states of grace, elegies!

Alongside “The Concert of Sighs”, stand two works, “Raven’s Choice” and “Schlupfloch” – which, in Horn’s similarly characteristic style, introduce a sensual lightness, a sense of humor and even erotic tone, which call up images of hair tickling our skin and pushing us to ask, where do sighs truly originate from?

Rebecca Horn composes a polyphony of senses – a visceral and physical experience opening at Galerie Thomas Schulte.