Sarah Entwistle

The knots of tender love are firmly tied

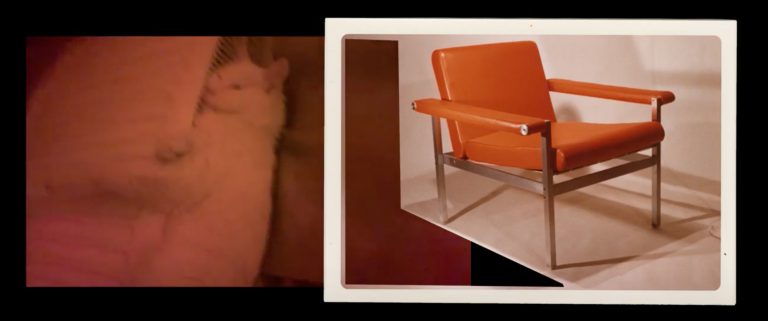

Sarah Entwistle, The dupe of another, 2021, mp4, 9:02min, Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm

Sarah Entwistle (b. 1979) works across multiple forms and often with found ready-mades to develop sculptural arrangements that recall interior still-lives. These assemblages take their visual and conceptual cues from the informal archive of her late grandfather, architect Clive Entwistle (1916-1976) a manipulative figure whose numerous female lovers were drawn into often masochistic dynamics. In her first solo exhibition in Berlin Entwistle continues with the practice of spoliation in its expanded form, of borrowing and adaptive re-use of material from earlier constructs. Her extended practice, a form of inter-generational processing both literal and metaphysical, is presented here through the accumulation and assembly of sculptural elements, video, figurative sketches, and woven tapestries. A collection of metal offcuts, industrial scrap, and crushed steel shelving units sit in still-life together with hand woven tapestries, ceramics and lighting elements that allude in scale, form, and composition to a domestic interior arrangement. A recurring motif of hands, seen as the conduits for caring and the cat’s paw knot as the allegorical structure of inter-generational exchange are explored in the video work, The dupe of another, and in figurative studies on paper.

Sarah Entwistle, The dupe of another, 2021, mp4, 9:02min, Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm

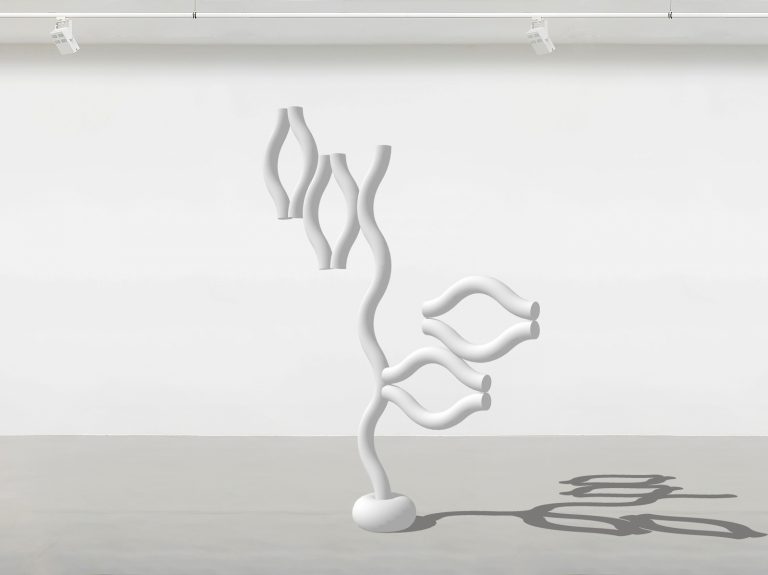

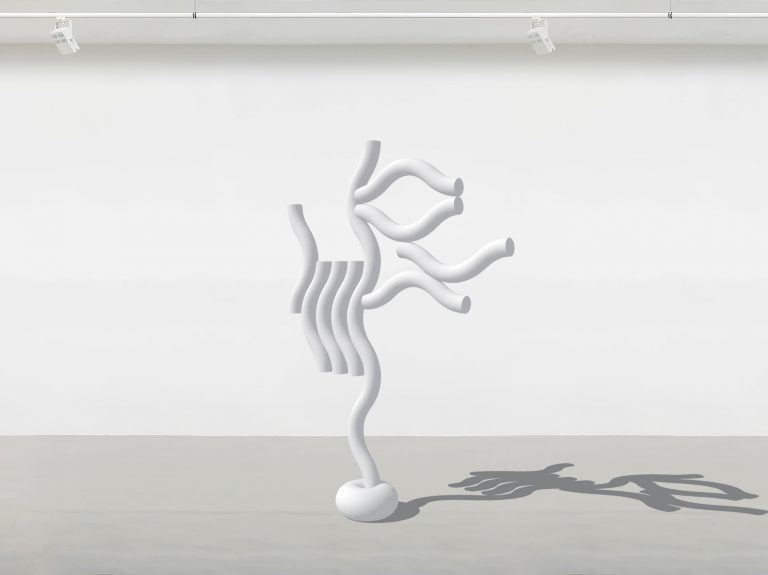

Sarah Entwistle, „The knots of tender love are firmly tied“, Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm, Installation View photographed by Jens Ziehe

Sarah Entwistle, „The knots of tender love are firmly tied“, Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm, Installation View photographed by Jens Ziehe

Sarah Entwistle, „The knots of tender love are firmly tied“, Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm, Installation View photographed by Jens Ziehe

Sarah Entwistle, „The knots of tender love are firmly tied“, Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm, Installation View photographed by Jens Ziehe

Diango Hernández

Instopia

A smaller version of the current show Instopia by Diango Hernández will be on view at the showroom.

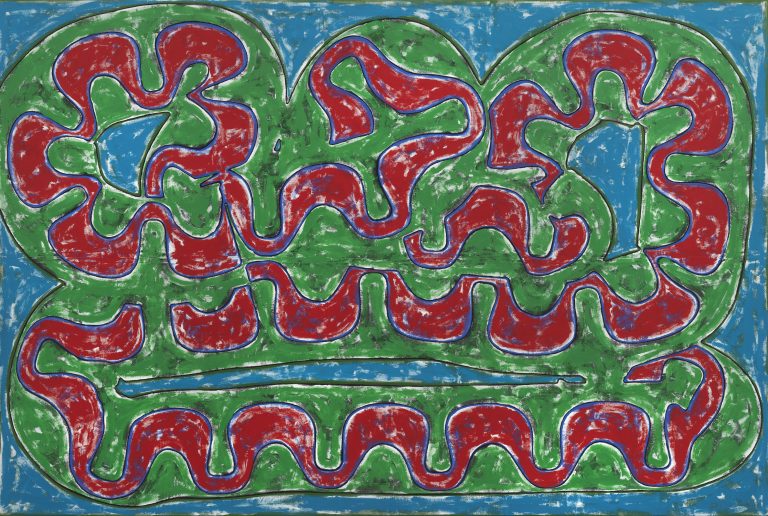

Diango Hernández, Espuma, mirándote, 2020. Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm

Diango Hernández, Espuma, bailando 2020. Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm

Simultaneously real and ethereal, Hernández’s work creates permanently ongoing stories and twists the boundary between functional design and fine art, between the social potential and promise of applied art and the free thought inherent in the perceptual experience of autonomous artworks.

Marcus Lütkemeyer, 2015

Diango Hernández, Espuma, bajo el agua 2020. Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm

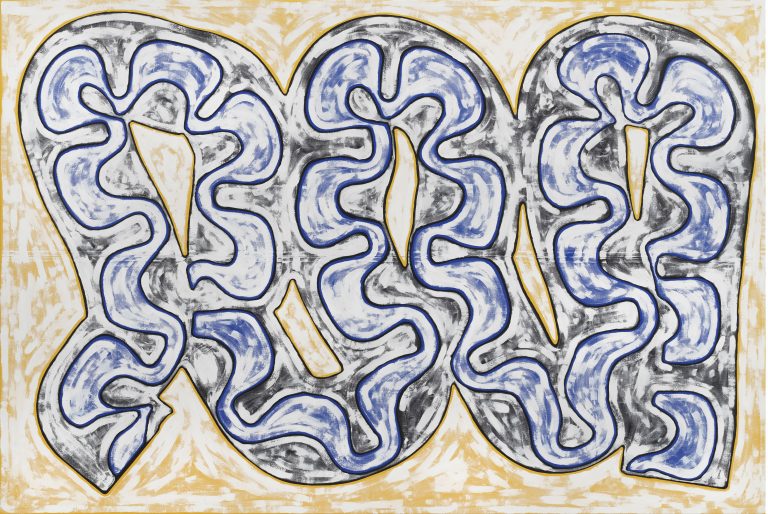

Galerie Barbara Thumm presents INSTOPIA, Diango Hernandez’s sixth solo show at the gallery.

Instopia is a radical and timely show for this moment of flux in which the boundary between the virtual and physical worlds is becoming increasingly porous. It is the first physical manifestation of Instopia, Hernandez’s Instagram art project, begun in 2015, which he explains thus:

“The process begins with me finding an image of one of these luxurious spaces on Instagram or online. Then I design a virtual artwork, it could be painting, a mural or a sculpture, that I think would look perfect in that particular, photographed space. Then I digitally place my artwork into the image of that space and post up this new picture onto my Instagram account. The work only becomes Instopia only when makes you believe that it’s ‘real’.”

Hernández’s protest is political, for the future, but it’s also a protest against history. “At a certain point, contemporary art has to remove itself from any kind of cultural reference.

Ajay Hothi, 2013

Exhibition view Diango Hernández, Instopia, Galerie Barbara Thumm, 2021, Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm, Photo: Jens Ziehe

Transgressing conventional notions of copyright and private property, long-since projected into virtual space, Instopia has caused, for some, outrage and offence. Hernandez’s intent was indeed to question the wholesale colonisation of digital space, believing “that transforming images and the values they embody is one way of transforming our reality, culturally and socially. I want people to interact more thoughtfully with images and to create ‘better’ pictures.”

At Galerie Barbara Thumm, Hernandez, for the first time, exhibits paintings and sculptures that began their existence as virtual objects within his Instopia.

Instopia foregrounds the politics of the ontology of virtual space, an increasingly urgent concern as the digital and meatspace melt, ever faster, into one another.

Nick Hackworth

Diango Hernández, Dancing Blue, 2021. Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm

Diango Hernández, Orange Flower, 2021. Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm

Diango Hernández, Un día en él Sur, 2021. Courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm