11 Sep –

17 Oct 2020

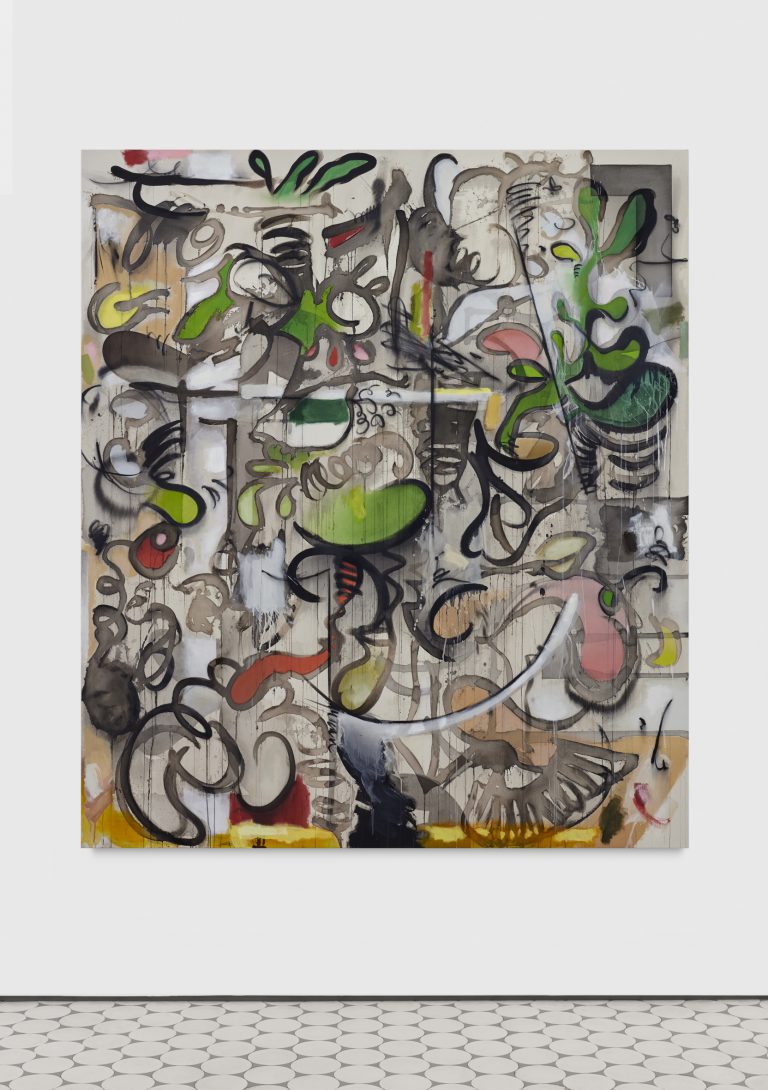

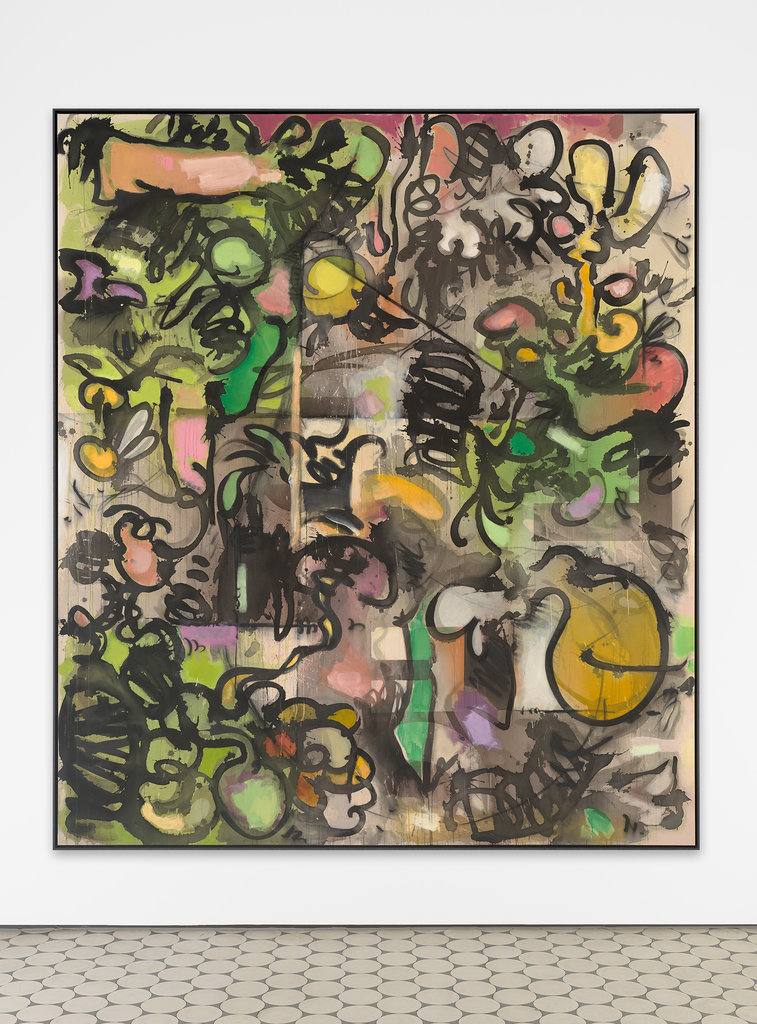

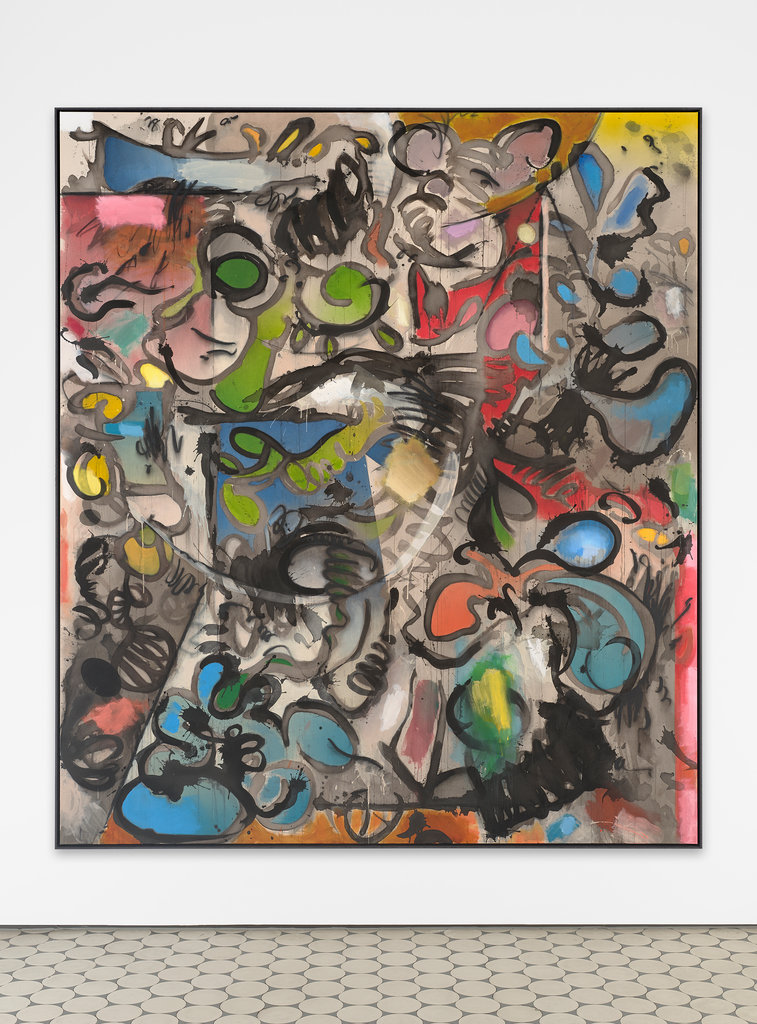

Jan-Ole Schiemann

Mantis Mannequins

09 Sep –

13 Sep 2020

Group Show

Tell me a tale

Jan-Ole Schiemann

Mantis Mannequins

Jan-Ole Schiemann, Matcha Mantis, 2020. Courtesy: the artist and Wentrup, Berlin. Copyright: Mareike Tocha

On the occasion of this year’s Gallery Weekend Berlin, Wentrup is pleased to present the first solo show by Jan-Ole Schiemann at the gallery: Mantis Mannequins.

Based on a visual vocabulary of complex forms and surreal body fragments, Jan-Ole Schiemann’s works oscillate between abstract painting and anthropomorphic figuration. His pictorial worlds create a dense, sometimes transparent mesh that abandons the contours of clearly defined, spatial structures in favour of interwoven compositions. The structures of the pictorial space, created on the basis of stencils and shadowy fields of ink, seem to work themselves deeply into the pictorial planes. In the paintings, they are delicately woven to form a superimposing net, which, in the manner of collages, takes up the multiple references to comics, gestural abstraction, and early animation film, and combines them in ever new variations.

The large-format works come about not just in dialogue with their references, but also link themselves in a continuous interchange to a formal language created in drawings and watercolours. In this language, pencil and ink organically outline details, dismember hybrid bodies, and link sections of lines – and then reshape themselves synthetically in the paintings in front of us into a wholly new visual universe.

Jan-Ole Schiemann, Homegrown Mantis, 2020, 230 x 200 cm / 90 1/2 x 78 3/4 in, ink, acrylic, charcoal and oil pastel color on canvas. Courtesy: the artist and Wentrup, Berlin. Copyright: Mareike Tocha

Jan-Ole Schiemann, Supernatural Mantis, 2020, 230 x 200 cm / 90 1/2 x 78 3/4 in, ink, acrylic, charcoal and oil pastel color on canvas. Courtesy: the artist and Wentrup, Berlin. Copyright: Mareike Tocha

Based on the associative universe of forms of a pencil drawing, Mantis Mannequins is also subject to a symbiotic concept of relations, on whose basis the works in the new series were created in close relation to one another – both formally and in terms of motifs. The drawing is the point of departure, the original idea, from which different articulations of painting develop in a pseudo-revolutionary process.

Powerful, and determined by signal-like paint blotches in shimmering shades of red and blue, on the one hand they create a dynamic thicket, where the modules of the original form elements adapt themselves cleverly. In another painting, in contrast, they turn into staggered black lines where they can only be sensed rather than properly seen, and which seem calm only at first sight. Only to suddenly reveal their organic body parts, consisting of circles, spirals, and abstract antennae between dark overlays, hinted-at geometric segments, or in a mixture of shapes running into each other in hues of red, black, and white. Contours, lines, and fields update themselves rhythmically as the result of an automatic drawing process. Painting and drawing here know of each other because they are related, since the fragments of the originally drawn composition take on a life of their own as fragments in the painterly work of the series as environments – as relationships of object and surroundings, and ambivalent spatial structures.

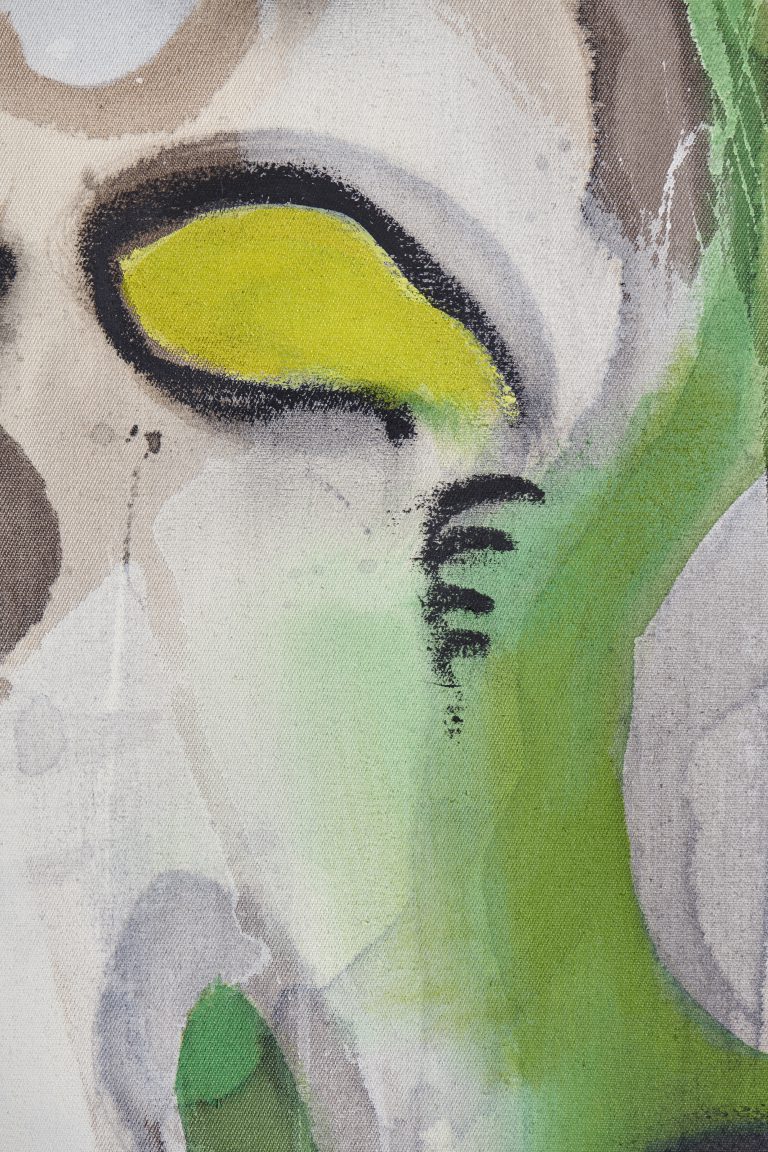

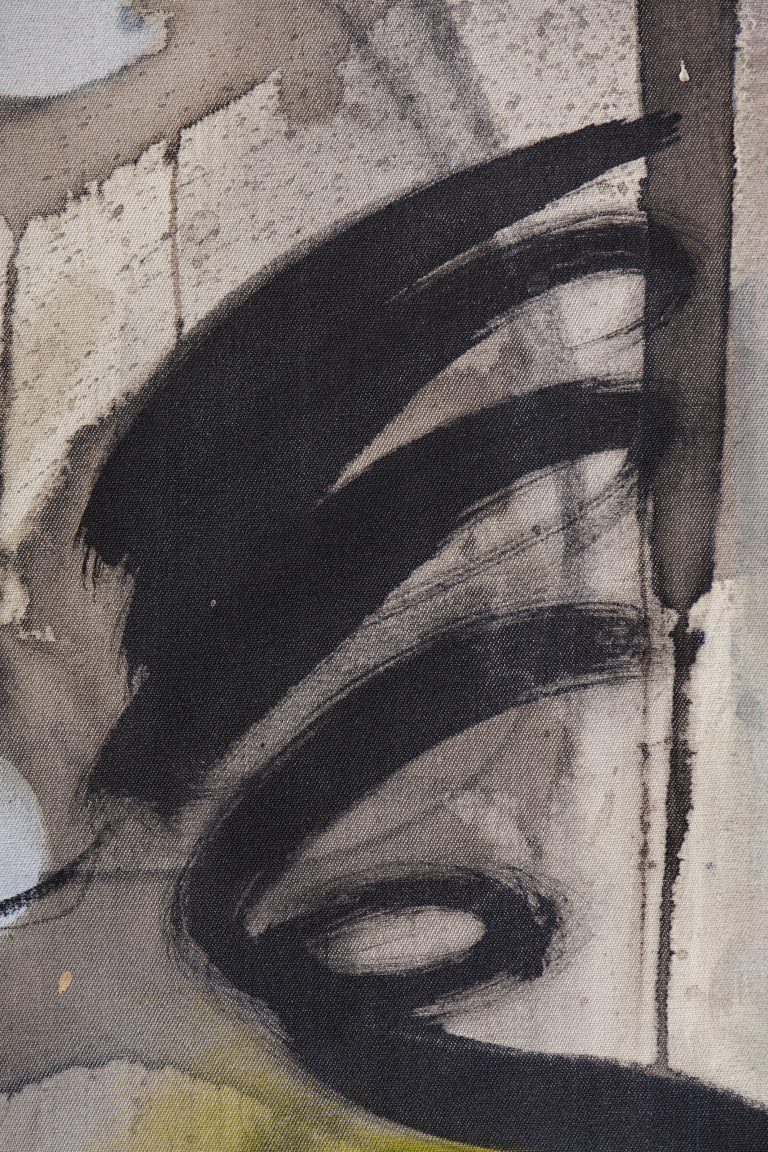

Jan-Ole Schiemann, Matchaman, Detail, 2020. Courtesy: the artist and Wentrup, Berlin. Copyright: Mareike Tocha

Jan-Ole Schiemann, Matchaman, Detail, 2020. Courtesy: the artist and Wentrup, Berlin. Copyright: Mareike Tocha

Jan-Ole Schiemann, Matchaman, Detail, 2020. Courtesy: the artist and Wentrup, Berlin. Copyright: Mareike Tocha

Like the process of composition, the underlying drawing is also a medium of a cognitive process, during which the figure of the mantis, which also lends the work its title, reveals itself in outline before our eyes. Derived from the praying mantis or, in Latin, mantis religiosa, it stands, like every single picture, for an embodiment of diversity. For a series of different forms of appearance, in which it lustfully and colourfully presents itself, sometimes all the way to invisibility, like posing mannequins. As an extreme example of evolutionary niche formation and adaptation to its environment, it moves as an anthropomorphic motif like a humorous figure, seemingly without a care in the world, through the paintings of the series. Elegantly bent und with large eyes before a vaguely outlined background that dissolves into a mixture of faintly pink and yellowish-orange clouds of colour, as an imitation of a layering of shapes, or as a figurative silhouette whose contours suddenly appear between deeply green colour fields. All these observations seem to be appropriate for describing the mischievously formal game of hide and seek, of mimicry on the canvas. A camouflage effect through which the compositions evade the beholder’s gaze to the same degree to which they reveal themselves in the next moment as their own formal counterpart.

The figure of the mantis becomes a symbolic animal here, whose ability to constantly change between camouflage and revelation not only facilitates a playful retreat into a visual world that is closed to our perception. Rather, it is also a sign of painterly and evolutionary freedom that mixes idealized narratives of the animal, visual and plant world, revealing the works’ gestural compositions as projection surfaces that expand our emerging associations in the process of continuous self-abstraction.

Like mannequins, the paintings change their partially grotesque-fantastical appearance, and point in their constant digestion of their original repertoire of forms to the rupture of their self-generated plan or design as a necessary condition of their composition. In so doing, the compositions turn their graphic lines inside out, interlocking themselves anew with the organic structure of forms, and laying down once again traces that point ambivalently both to their origin and their updating. To a process where the mantis, as the title suggest, proverbially becomes a mannequin – a symbol that allows us to grasp figuration and abstract painting as something fluid, connecting them mischievously through masking and imitation, in a continuous transformation of form and colour.

Philipp Fernandes do Brito

Studio view

“My exhibition Mantis Mannequins is based on a drawing from 2019 that always reminded me a little bit of a praying mantis. In large-scale paintings, this insectoid cipher takes on a variety of colors and different characters in order to form a polyphonic interplay in the exhibition space.”

Jan-Ole Schiemann

Jan-Ole Schiemann. Courtesy the artist and Wentrup, Berlin. Photo: Carson David Brown

Jan-Ole Schiemann (born in Kiel in1983) studied at Kunsthochschule Kassel and at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf with Albert Oehlen and Andreas Schulze. He was a member of Andreas Schulze’s master class.

Works by Jan-Ole Schiemann are in numerous collections, including the Bronx Museum, New York; the Craig Robins Collection, Miami; the Hort Family Collection, New York; The Marciano Collection, Los Angeles; the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit; the Rubell Family Collection, Miami; and the Margulies Collection, Miami.

Nevin Aladağ, Natalie Ball, Jerrell Gibbs, Sophie von Hellermann, Caitlin Keogh, Florian Meisenberg, Devan Shimoyama and Francis Upritchard

Tell me a tale

Wentrup is pleased to present the group exhibition Tell me a Tale during Berlin’s Gallery Weekend in external rooms close to the gallery.

Taken from the eponymous 2012 track by British singer-songwriter Michael Kiwanuka, Tell me a Tale is the title and concept for the group exhibition, that features a selection of artists whose works depict processes of ‘telling tales’. Over the course of many centuries, artists have created works of art that tell stories –by presenting narratives from personal histories or other people’s lives and experiences; Artists’ have created and presented narrative in many endless ways, contextualizing or decontextualizing already existing material to form his or her own story – even by invention – inviting the viewer to imagine the narrative themselves.

Tell me a Tale demonstrates the many differing processes and notions the selected artists hold in the telling of stories in their art– from a composed clarity in directing the subjective narration; to themes of empowered, personal artistic responses: there are countless viewpoints and countless angles in which stories can (and indeed are) told.

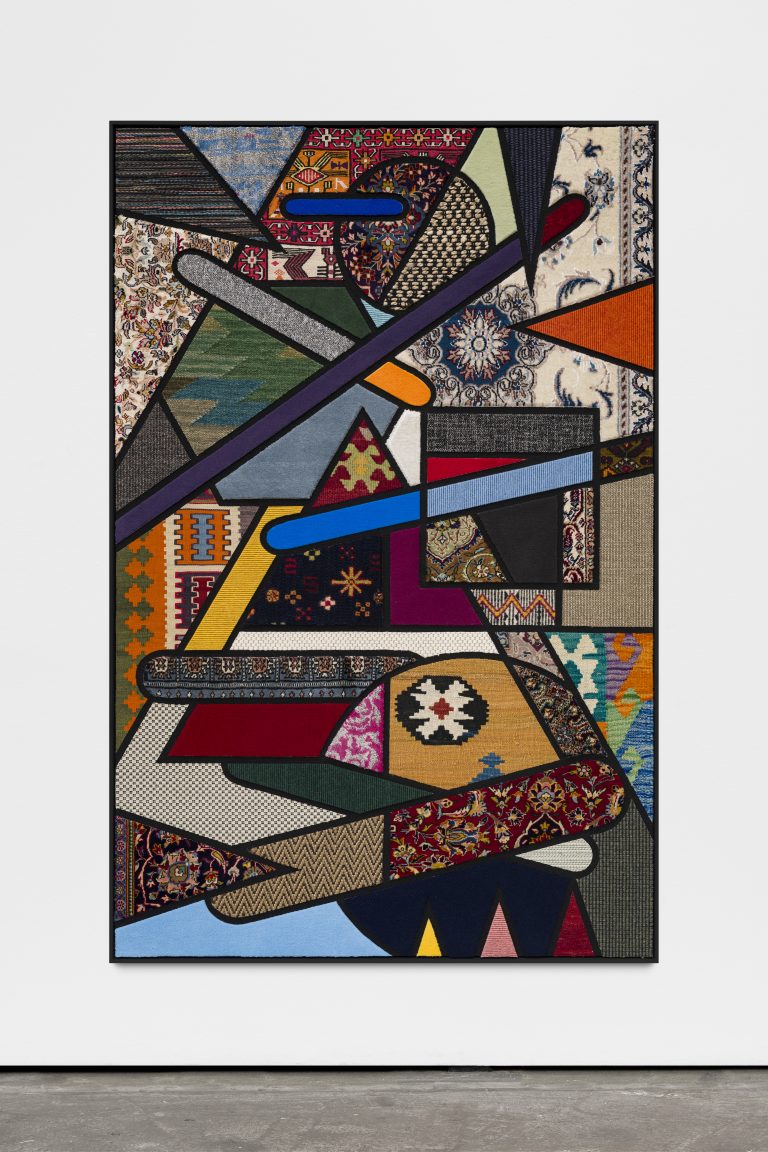

Nevin Aladağ (*1972) frequently uses music and musical instruments in her sculptures, collages, performances, and videos to consider the ways identities are made and communities are formed. Born in Turkey and raised in Germany, where she continues to live and work, Aladağ playfully explores relationships among cultures, traditions, and geographies. The artist’s most recent series, Resonator (2018–present), combines musical instruments from around the world as abstract geometric forms to create new sounds. The sculptures bring together elements of disparate heritage, inspiring wonder and curiosity as they engage themes of transformation and belonging. In her series Social Fabric (2014–present) abstract compositions pieced together from carpets of unique material, method, and origin.

Aladağ’s first major solo museum exhibition in the U.S. at SFMOMA just ended in August. Currently a site-specific room installation is on view at Kunsthalle Mannheim, Germany. In May 2021 she will have a solo exhibition at Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg, Germany.

Nevin Aladag, Social Fabric, Percussion III, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Wentrup, Berlin, Photo: Trevor Good

Natalie Ball, Breast Plate (series), 2019. Courtesy the artist, Nino Mier Gallery, Los Angeles and Wentrup, Berlin

Natalie Ball, a citizen of the Klamath tribes, is best-known for repurposing and re-contextualizing found materials and media that often confront the reductive narratives surrounding Native American identity. Working from her ancestral homelands in the rural community of Chiloquin, Oregon, Ball approaches her sculptural work to challenge the narrative surrounding the Native American experience and history. Ball’s use of materials is wide-ranging, often incorporating traditional, indigenous materials with found objects ranging from textiles, leather, beads, and wood to coyote teeth, hair, fur and bone. It is this juxtaposition, which sometimes bordering on the absurd that allows Ball to create a new auto-ethnographic narrative as she excavates hidden histories, and dominant narratives to deconstruct them through a theoretical framework of auto-ethnography to move “Indian” outside of governing discourses in order to build a visual genealogy that refuses to line-up with the many constructed existences of Native Americans.

In the exhibitied series, Ball explores gesture and materiality to create sculptures as “Power Objects” a term used to describe shared cultural symbols or objects. Purse First shows Ball’s wit and is made with a Cedar Hat by the artist Paul E. Rowley of the Haida & Tlingit Tribes. Ball has incorporated his hats into many of her anthropomorphic sculptures. Through these woven identities, Rowley and Ball show the marriage of culture and time. The bowler hat is a symbol of wealth and sophistication and Ball parodies the stereotype of women who put their purse first with a cockeyed sheriff’s pin. The woman has an ombre weave incorporating a rich turquoise blue color.

Breast Plate evokes imagery of armour, combat and strength but speaks to the modern identity of those who live and trade on the reservation as it incorporates bone that is used as a currency. Similar to wearing swarvoski crystals, adorning bone signifies swag or cultural caché that is paired with the chenille.

Natalie Ball (*1980 in Portland) lives and works Chiloquin (Oregon). She received her M.F.A. in Painting & Printmaking from Yale University, New Haven.

Ball has been included in numerous exhibitions at prestigious institutions, such as the SculptureCenter, New York, Museum of Contemporary Art, Miami, IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, Santa Fe, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. 2019 she had a solo exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum.

Jerrell Gibbs brings movement and life into the setting of his paintings with vibrant, lively, backgrounds. The subjects are static, his figurative painting style and unmistakable expression affirm the multilayered experience of African-Americans by accentuating Black identity through empathetic and authentic lenses.

The entire arrangement of Jerrell Gibbs’ work focuses just as much on placement, size, and proportion, as it does on a painterly gesture. His claiming of that legacy performs a powerful sort of displacement for an audience unaccustomed to more extensive and wide-ranging portrayals of Black life. He retraces family memories, examining the origin of his own life by representing intimate and instantly joyous moments. While affirming the multilayered experience of the African-American diaspora, Gibbs plunges the viewer into an immersive experience, the realm of his childhood. Growing up in Baltimore influenced his perspective of socio-economics, body politics, race, economic disparities and their influence on one another. Through his figurative portraits, Gibbs accentuates conventional representations of black identity by depicting empathy, inviting the possibility for a spiritual connection. The works are adapted from small polaroids into life-size paintings. The artist draws from revised characters in his own life and narratives such as Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts, mimicking their playful illustrative style.

Jerrell Gibbs (*1988; born and based in Baltimore, MD) graduated with an MFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, MD in 2020. He has exhibited at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum, The Galleries at CCBC and The Gallery at Howard University. His work appears in the permanent collection in the Harbor Bank of Maryland, the X Museum and most recently the Columbus Museum of Art.

Jerrell Gibbs, Day today, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Mariane Ibrahim

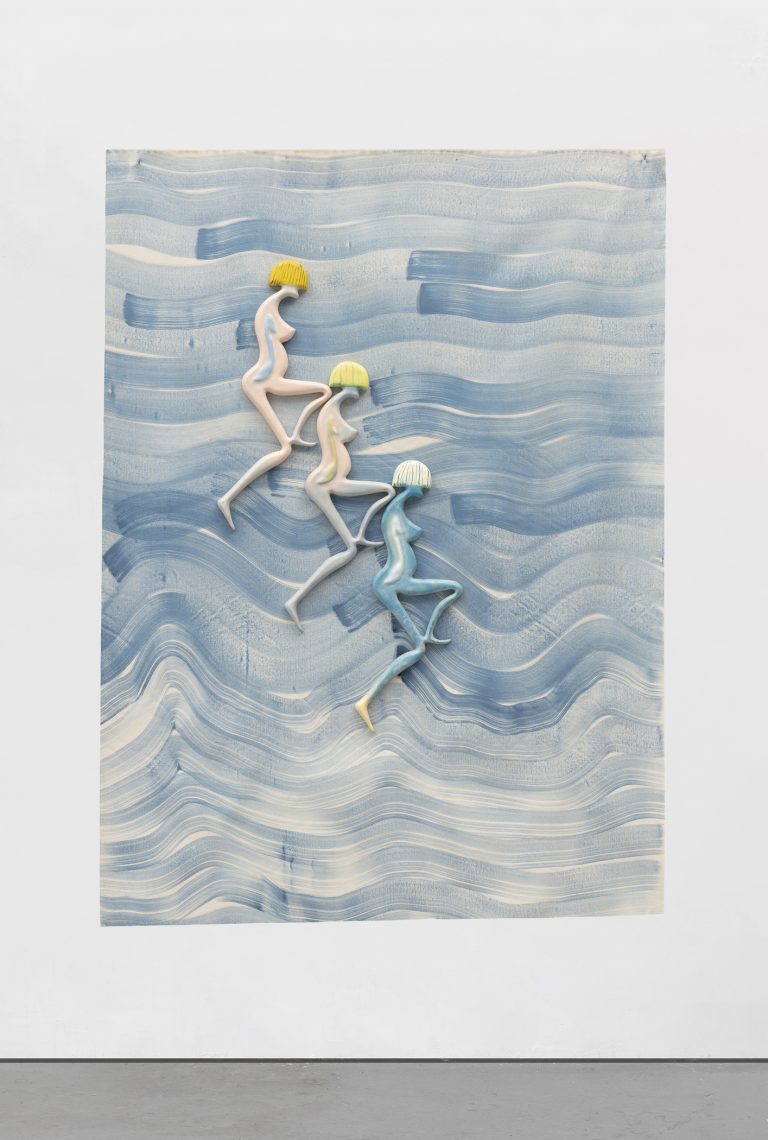

Sophie von Hellermann, Spread your Wings, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Wentrup, Berlin

Sophie von Hellermann‘s paintings recall the look of fables, legends and traditional stories that are imbued with the workings of her subconscious rather than the content of existing images. Her romantic, pastel-washed canvases are often installed to suggest complex narrative threads. Von Hellermann applies pure pigment directly onto unprimed canvas, her use of broad-brush washes instills a sense of weightlessness to her pictures. The artist’s paintings are drawn upon current affairs as often and as fluidly as they borrow from the imagery of classical mythology and literature to create expansive imaginary places. In subject matter and style, von Hellermann tests imagination against reality.

The painting “Spread your Wings” refers to a story that a friend of the artist wrote but was not yet published when the painting was created. Sophie von Hellermann had received the manuscript, which is about the daughter of a scientist named Sophie. Ignorant of her magical powers, the girl creates by mistake a human-bird hybrid out of herself.

Sophie von Hellermann (born 1975 in Munich, Germany) lives and works in London and Margate, U.K.. She studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in Germany and the Royal College of Art in London, U.K..

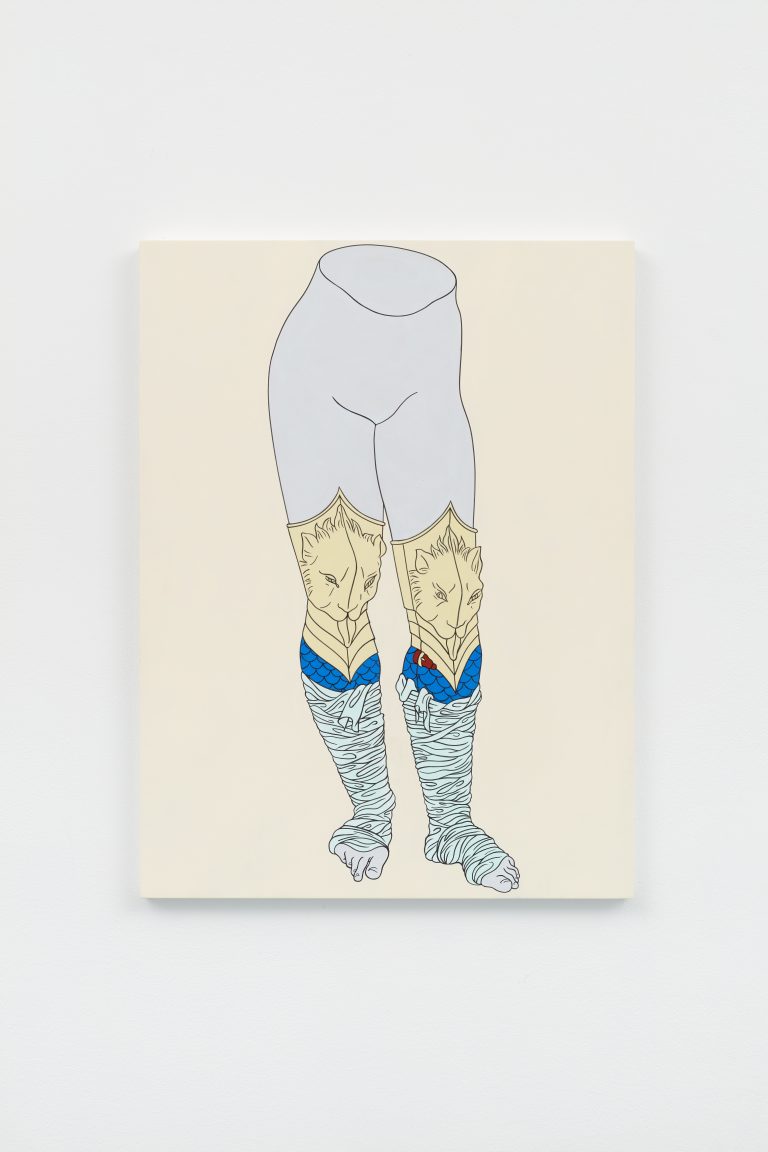

The legs in the painting Legs by Caitlin Keogh are modeled off of the legs Saint Michael in a painting by Carlo Crivelli that is on view at the National Gallery in London. The posture and armor of the lower leg is modeled in that painting, but the body in Keogh’s painting has been neutered, in terms of gender, now slightly more feminine but genitally blank. The style in which Keogh has “rendered” the motive is based on drawing as a tool for fabrication and production–technical illustration. The information of an object is reduced to its most simplistic, a practical stand in for written language. In the process of drawing the artist proceeds from the question, “what information is necessary to recreate this object elsewhere?” This communication-imperative in the place of gestural or personal expression, as a mode of image-making by hand, is not superficial or nullifying–it is concentrating the subject of the artwork, and the labor of producing it, into the line itself. Perversely, the depersonalized line is not a graph of mere data, it is the animate figuring of thought in relation to craftsmanship and process. For Keogh the Crivelli body is interesting in terms of Crivelli‘s style, which is both highly graphic and legible but also soft and decorative; the anthropomorphism of the armor, the human body is conjoined with the lion in the fantastical armor; the symbolism and unreality of the depiction of the depicted event- the space is strange, the calm sense of stasis, the symbolic iconography is crammed in everywhere.

Caitlin Keogh (*1982 in Anchorage, Alaska) lives and works in New York. She studied at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris, France and graduated from MFA Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts, Bard, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY.

Caitlin Keogh, Legs, 2020. Courtesy the artist, The Approach, London and Bortolami, New York

Florian Meisenberg, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Wentrup Gallery, Berlin

Florian Meisenberg experiments with the possibilities of the depicted image. Much of his work reflects self-consciously upon both the process of painting and the specific boundaries of the medium. His investigations have led him to paint both figuratively as well as abstractly, playing with issues of scale that create complex installations (or environments), and explore the permutations of different materials (whether those used for support or types of paint or digital media), all in the service of expanding the potential of non-verbal communication. These are works that in their constant awareness of the constructed nature of visual experience nevertheless present to viewers images containing the expressive power of an unmediated here and now.

After graduating at Peter Doig’s masterclass at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 2010 Florian Meisenberg (*1980 in Berlin, Germany) moved to New York, where he now lives and works.

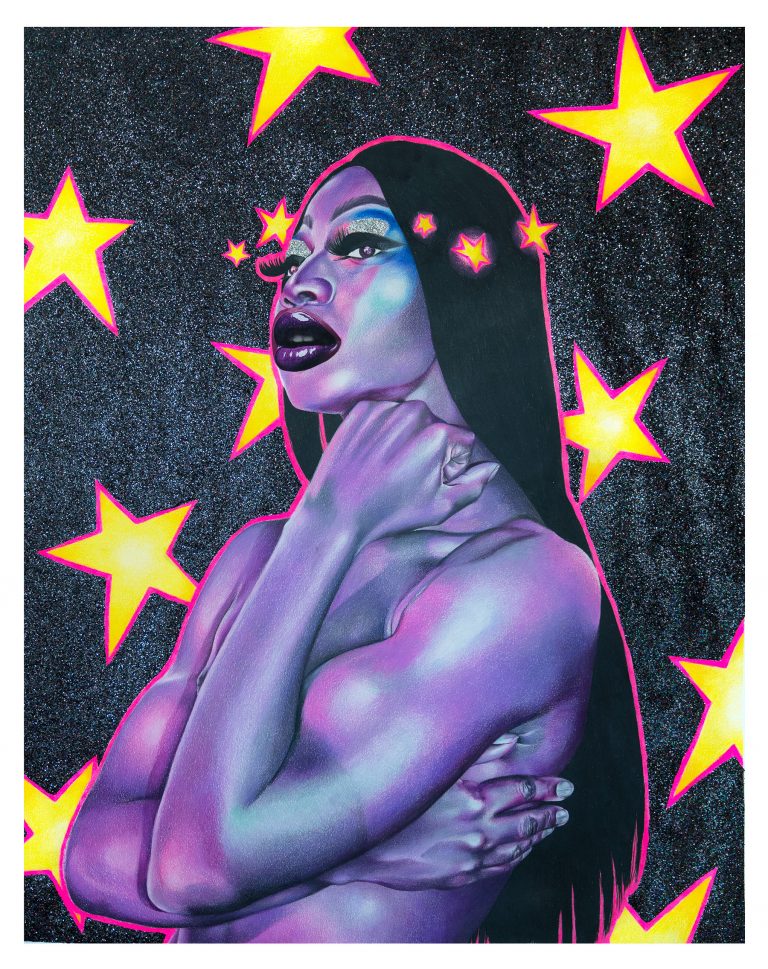

Devan Shimoyama is a visual artist working primarily in self-portraiture and narratives inspired from classical mythology and allegory. Shimoyama seeks to depict the black queer male body as something that is both desirable and desirous. He explores the mystery and magic in the process of understanding his origins and also investigates the politics of queer culture.

The work of Devan Shimoyama showcases the relationship between celebration and silence in queer culture and sexuality. Shimoyama’s composition is inspired from the canons of the masters Caravaggio and Goya, though adding a more contemporary expression and sensuality. With the usage of various materials: splattered paint, stencils, black glitter, rhinestones, and sequins, Shimoyama creates pieces that capture the magical spirit of human beings.

Devan Shimoyama (*1989 in Philadelphia, PA) was awarded the Al Held Fellowship at the Yale School of Art in 2013 and has had a residency at the 2015 Fire Island Artist Residency. Shimoyama’s work has been exhibited throughout America on numerous occasions. His exhibition Cry, Baby was on view at the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh from in 2019. Shimoyama’s new and existing work was paired with a rotation of Warhol’s Ladies and Gentlemen paintings from 1974, revealing new perspectives on Warhol’s practice, embracing contemporary debates about identity politics, gender and sexuality in addition to issues of racial violence and tension in the United States.

|

Devan Shimoyama, The Embress, 2020. 121.92 x 96.52 cm / 48 x 38 incolored pencil, glitter, acrylic, collage and rhinestones on paper. Courtesy the artist and De Buck Gallery, New York |

Francis Upritchard, Grumpy Grumpy Grumpy, 2019. 53 x 35 x 50 cm / 20 3/4 x 13 3/4 x 19 2/3 insteel and foil armature, paint, modelling material, fabric and hair. Courtesy the artist and Kate MacGarry, London

With her enigmatic figurative sculptures, New Zealand artist Francis Upritchard occupies a unique position within the contemporary sculpture scene. Upritchard’s oeuvre is characterized by in-depth experimentation with material, colour, shape and scale. The sculptures are devoid of any cultural, geographical or chronological boundaries. References can range from Mokomokai and Japanese folklore to futuristic hippies. Fascinated by museology and design, Upritchard often presents her sculptures in self-designed displays and scenography. Their colourful eclecticism, serene poses, closed eyes and contemplative posture invite associations. Recurring references often include loom weaving, Native American patterns, medieval mythology and the indigenous Maori culture of New Zealand. The sculptures, however, do not represent specific persons or characters. Gender, time and space are also kept deliberately vague and indefinable. They seem to hover between melancholy and ecstasy, between utopia and dystopia, object and subject. Upritchard likes this ambiguous quality: “These are all portraits of me, because it’s all my experiences and what I’ve seen and I’ve done. That’s why I do this loose research, so I can’t say I am going to represent any exact thing.”

Francis Upritchard (*1976 in New Plymouth, New Zealand) lives and works in London, UK.

This year the artist had a solo exhibition at the Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens in Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium. Further institutional solo exhibitions took place at The Curve, Barbican Centre, London, UK; LUX Art Institute, Encinitas, CA; Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA) Melbourne, Australia; The Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA; Whitechapel Gallery, London, UK; Amersfoort Kunsthal, The Netherlands and the Secession, Vienna, Austria.

2009 Francis Uprichtard represented New Zealand in the 53rd Venice Biennale in Italy. And she was part of the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017.