Published 13 DEC 2024

Mariana Castillo Deball

Vùjá de - Paper Thresholds

30 NOV until 1 FEB 2025

Galerie Barbara Wien is delighted to announce Mariana Castillo Deball’s fifth solo show at the gallery. Titled Vùjá de – Paper Thresholds, the exhibition comprises watercolour drawings, prints, sculpture, murals and installation, all of which focus on paper in different ways.

Installation Mariana Castillo Deball: Vùjá de – Paper Thresholds,

Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin, 2024

Artist Statement

As I frequently study documents which have been altered, destroyed or stored in distant and inaccessible libraries and museums, I often work with printed copies, facsimiles and digital reproductions. From a Western, art historical point of view, these copies are mere supplements of the original object, without any value of their own. Yet, it was the ravages of colonisation and looting that caused us to produce such copies in the first place, as a means of holding and protecting; if one goes missing, we will still have multiple versions. I would therefore like to think of this genealogy of copies as a dissonant polyphony, a collective yet anonymous heritage. We can think of these documents as objects that have experienced a trauma shared by the group protecting their memory. The Nahua concept of ixiptla can account for this multilayered approach. Translating to “representation,” “impersonation,” or “substitute,” it encompasses all these different versions, representations, and echoes, as part of the original, even if such an original no longer exists.

The title of the exhibition is inspired by Roy Wagner‘s book Coyote Anthropology (2010), in which the US-American anthropologist explores the concept of vùjá de – an inversion of the more familiar notion of déjà vu. Wagner critically discusses the role of the anthropologist and the object of anthropological study, looking at how the presence of anthropologists alters the environments in which they work. In this context, vùjá de refers to encountering something familiar but seeing it in a completely new, unexpected way – as if for the first time. Wagner suggests that vùjá de is a crucial aspect of anthropological thinking, encouraging defamiliarisation of the taken-for-granted aspects of culture. By seeing the familiar as unfamiliar, it becomes possible to understand and reinterpret it in innovative ways. When I read Coyote Anthropology, I felt that translating it into Spanish would be the only way to encapsulate the text. I contacted Wagner in 2010 and proposed a collaboration involving his words and my drawings. We kept up a correspondence that lasted several years and resulted in the publication of the book Antropología del Coyote: Una conversación en palabras y dibujos in 2018.

Installation Mariana Castillo Deball: Vùjá de – Paper Thresholds,

Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin, 2024

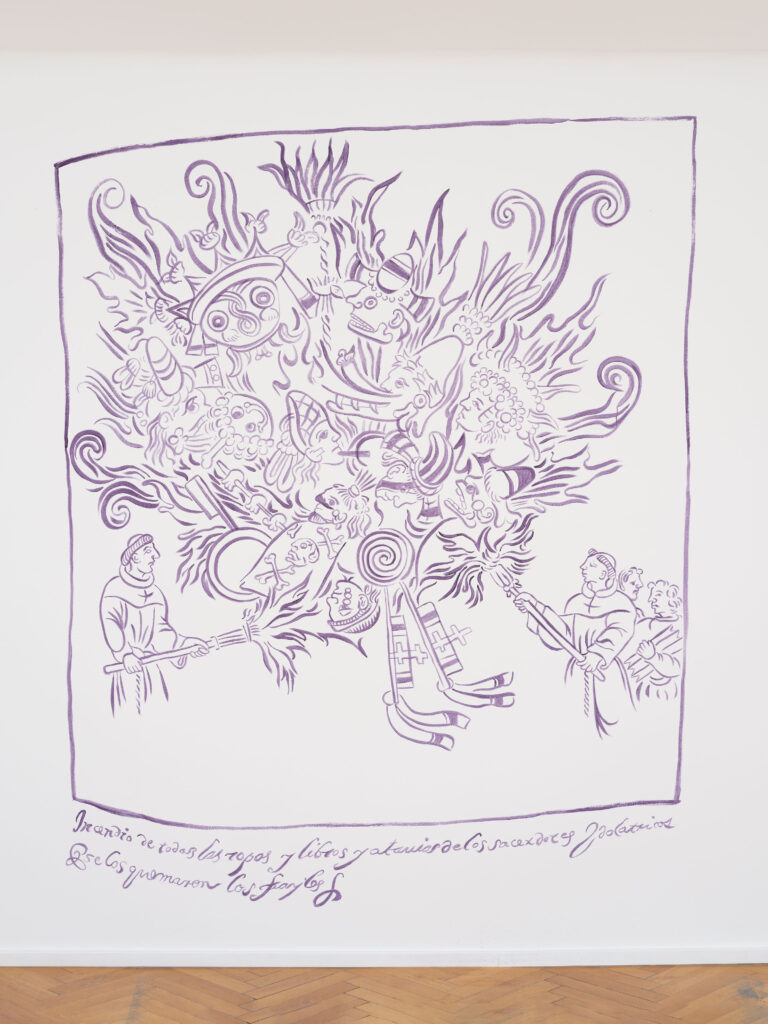

Burning of Idols,2024

Site-responsive mural

Contra Infantium Adustione 1, 2024

Watercolour on paper, framed

Entering the gallery, visitors pass under Paper Portal , an installation consisting of handmade sheets of paper suspended below the ceiling. When we think about paper, we often relate it to a volume in which many pages are bound to form a book. However, as artist Dorothy Field explores in her publication Paper and Threshold (2007), paper has been extensively used in public space to create portals and transitory spaces. In this form, handmade paper carries a spiritual and cultural significance, transcending its practical use to act as a bridge between the human and spiritual realms in cultures such as Japan, Korea, Burma, Nepal, and India.

The paper used for Paper Portal was hand-made in Berlin by Gangolf Ulbricht, who I have been working with since 2022. He is a specialised paper maker who uses traditional techniques and further develops them through collaborative experiments with artists and other paper enthusiasts. The paper pulp was dyed using cochineal – a natural, red dye which can also create hues of pink and purple depending on the pH level of its mixture. Cochineal originated in the Americas and is derived from the cochineal insect (Dactylopius coccus), a type of scale insect that lives on cacti and is native to Central and South America. Developed for textiles and art by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, primarily by the Aztecs and Maya in what is now central Mexico, cochineal was closely tied to colonial trade. It became a valuable export during the 16th century and highly sought after in Europe. Because it was far superior in colour and stability to red dyes from Europe, colonial Spain closely guarded the source of cochineal, treating it as a state secret to maintain their monopoly. I added drawings onto some of the suspended sheets of Paper Portal which refer to Diego de Valadés‘ Retórica Cristiana (1579). Valadés was a Tlaxcalan-Spanish friar who sought to evangelise native peoples and teach them how to read and write. These specific drawings address the censorship imposed by the colonial state, prohibiting native languages and ceremonies. The “forbidden” native words and actions are depicted as insects and snakes emerging from the characters.

Using the leftover pulp from the paper-making process, we created a series of papier-mâché reliefs at the studio. In the exhibition, I am showing both the ceramic moulds we used to create these reliefs, titled Vùjá de, and the papier-mâché works themselves, Déjà vu, thus blurring the Western hierarchy of original and copy in the spirit of ixiptla.

I have been working with natural pigments from Mexico, like cochineal, and their history since 2018 when I collaborated with researcher Tatiana Falcón on the exhibition In Tlilli in Tlapalli, Imágenes de la nueva tierra: Identidad indígena después de la Conquista at the Museo Amparo in Puebla, Mexico to create pigments. We planted a garden for trees, wild seasonal plants, bushes, insects, and lichens named in the Florentine Codex (ca. 1540–1569) as the ingredients necessary to make the most important coloured pigments and dyes used by the Nahua, one of the Indigenous peoples of Mexico.

The series of framed watercolour drawings in the south room, titled Contra Infantium Adustione, is also made with pigments that Falcón elaborated. This time, the pigments and the drawings’ motifs are based on the plants depicted in the Codex Cruz-Badiano. This codex, written in 1552, contains Nahua medicinal recipes compiled by Indigenous scholars of the College of Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco. I began by making sketches based on a drawing from plate 53 of the Codex Cruz-Badiano. I liked this drawing in particular because the roots of the plant grow out of and around a stone, with water coming out of its centre. I tried to imagine what it would be like to get into the centre of that stone – root – water and draw the plant from there. I liked this exercise because it was no longer about the repetition or copy of the original drawing, but about finding a new place from which to feel the growth of the plant. After many sketches, I finally dared to start painting with Tatiana‘s pigments, which took some time getting used to since I had to understand how and with what to mix them. The drawings gradually escaped from their original referent, the Codex Cruz-Badiano, and became a means to spread the precious luminous liquid as the pigments, their brilliance and materiality became the protagonists.

The two murals in the gallery‘s south and north room also refer to manuscripts from the region that is now Mexico.

Installation Mariana Castillo Deball: Vùjá de – Paper Thresholds,

Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin, 2024

Crocodile Skin of the Days, 2021

Silkscreen on Pergamin paper,

wood sticks, wooden spindle

Vùjá de 6, 2024

Ceramic relief

The wall painting, Burning of Idols, in the south room is based on a drawing of the same name from the historical manuscript Description of the City and Province of Tlaxcala (1581–1584) written by Diego Muñoz Camargo, a Mestizo (meaning of Indigenous American and Spanish ancestry) historian from New Spain. The manuscript emphasises Tlaxcala‘s role as a loyal ally to Spain and its contribution to the fall of the Aztec Empire, blending traditional Mesoamerican pictorial styles with European influences. This specific drawing depicts the destruction of images, masks, and religious paraphernalia of Nahua deities at the hands of Catholic friars in the 16th century, shortly after the Spanish conquest. As a Catholic and a loyal servant of the Spanish crown, Muñoz Camargo supported the destruction of these “idols,” yet he meticulously rendered the masks of specific Nahua deities, like Quetzalcoatl and Ehecatl, above the flames. Muñoz Camargo‘s account thus preserves the pre-colonial past, records its destruction and depicts the dawn of a new Christian age.

The second wall painting, Crocodile Skin of the Days, which runs along one of the walls in the north room, refers to plates 39 and 40 of a Tonalamatl (Nahuatl, meaning “book of days”) known as the Codex Borgia (ca 1300–1500). The Tonalamatl is one of the few pre-colonial calendars of Indigenous peoples in Mexico which survived the destruction of colonisation. Crocodile Skin of the Days (2024) focuses on the image of a reptile skin found in the ancient calendar, onto which glyphs and symbols representing the 20 day signs and 13 numbers are inscribed, combining them in various ways to create a 260-day cycle. I have been working with different iterations of this drawing for some years now. The first version was a small watercolour drawing, which was part of a previous exhibition at Galerie Barbara Wien in 2018, titled das Haut-Ich. Afterwards, I developed the motif into a wooden floor piece for the exhibition Amarantus in Mexico City, and a floor painting in the current exhibition Forgive Us Our Trespasses at Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin. In the north room of Galerie Barbara Wien, Crocodile Skin of the Days appears in three different ways, as paper kites, in a fragmented manner through the ceramic moulds and the papier-maché reliefs (2; 8), and lastly, as a wall painting.

A selection of prints, from the series She Bends to Catch a Feather of Herself as She Falls, is also on view in the north room. I originally developed these prints for the exhibition Ceremony (Burial of an Undead World) 2022 at HKW in Berlin and worked together with the paper producers Gangolf Ulbricht and Ulrich Kühle at Keystone Editions printing workshop in Berlin. It was a very interesting process comprising different steps in which I printed the motifs in blue, red and yellow, on three different papers developed by Gangolf Ulbricht. Once these prints were ready, I ripped them apart into small pieces and blended them into tiny particles. These crushed prints were added back into the paper pulp to make new sheets. Afterwards, I returned to Keystone Editions and we printed on top of the new paper sheets. The printed motif reworks shapes from a series of prints I did in 2010 titled Coatlicue #1–3. They refer to a monolithic statue of Coatlicue, the Aztec mother of the deities. This statue is believed to have been created a few decades before the Spanish invasion and is an important piece in the collection of Mexico City‘s National Museum of Anthropology. In She Bends to Catch a Feather of Herself as She Falls, Coatlicue appears as a fragmented yet majestic figure. The fractal appearance of a multiplied deity recalls her central and fertile position within the cosmological matrix of the Aztec belief system and social order.