Julian Irlinger

Sleepwalkers

12 SEP until 8 NOV 2025

Opening – 11 SEP 2025, 6-10 pm

At Potsdamer Strasse 81B,

10785 Berlin

Julian Irlinger

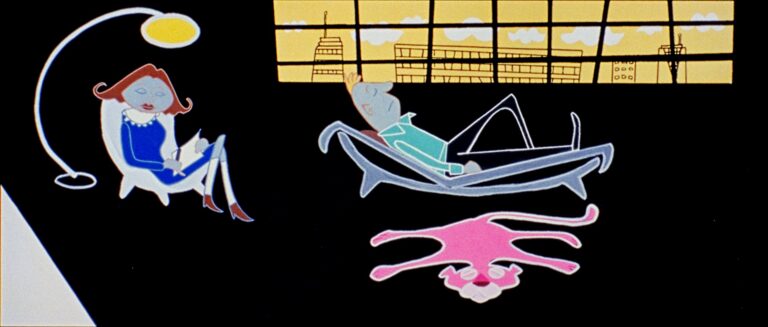

The Curtain of Time (detail of film still), 2025

16 mm film transfer to digital, color, sound, 10’50”, loop

Courtesy of Julian Irlinger and Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin

For his third solo exhibition at Galerie Thomas Schulte, Julian Irlinger is showing drawings, objects, and a video work—titled “The Curtain of Time” and commissioned by Portikus, Frankfurt/Main—collectively exploring the history and technique of hand-drawn cel animation and reflecting on the mediation of historical narratives. In his artistic practice, Irlinger approaches past events in sight of future conflicts. Through the excavation and recontextualization of historical fragments, his practice questions the mechanisms of memory and the transmission of history. Drawing on archives and historical aesthetics, his body of work—spanning drawing, film, photography, and sculpture—challenges dominant historical narratives and their cultural representations, as well as the ideological currents that shape them.

Julian Irlinger

The Curtain of Time (detail of film still), 2025

16 mm film transfer to digital, color, sound, 10’50”, loop

Courtesy of Julian Irlinger and Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin

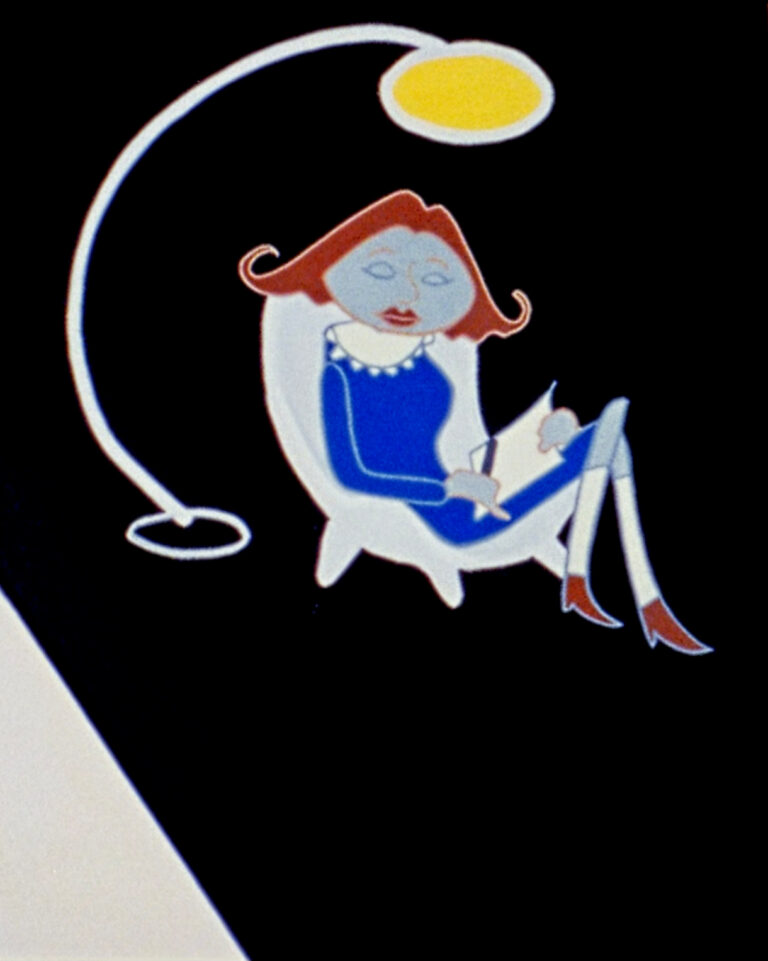

Julian Irlinger

The Curtain of Time (detail of film still), 2025

16 mm film transfer to digital, color, sound, 10’50”, loop

Courtesy of Julian Irlinger and Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin

Dan Walsh

Assembly

11 SEP until 8 NOV 2025,

Opening – 11 SEP 2025, 6-10 pm

At Charlottenstrasse 24

10117 Berlin

Dan Walsh

Reform II, 2024

70 x 70 inches, acrylic on canvas

Courtesy of Dan Walsh and Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin

During Berlin Art Week, Galerie Thomas Schulte presents “Assembly”, a solo exhibition of new paintings by Dan Walsh. Long recognized for his meditative approach to abstraction, Walsh deepens his exploration in this body of work by expanding his minimalist vocabulary—marked by subtly irregular shapes, shifting lines, and a distinctive sense of wit. Each of the seven works in the exhibition begins with a rigorously structured grid, which Walsh transforms into a complex visual system using a pared-down set of formal elements. Through the repetition and variation of simple geometric forms, he constructs linear patterns and visual rhythms that gradually unfold across the canvas. Upon closer inspection, these forms reveal the artist’s free, layered brushwork, resulting in nuanced transparencies and added complexity. As Walsh puts it, he is a “maximalist working within a minimalist paradigm,” seeking maximal visual resonance through minimal means.