Monsieur Zohore

Whether the Weather

11 SEP until 15 NOV 2025

Opening – 11 SEP 2025, 6-9 pm

Whether the weather be fine, or

whether the weather be not

Whether the weather be cold, or

whether the weather be hot, We’ll

weather the weather, whatever the

weather, Whether we like it or not.

Courtesy of the artist and the gallery

For his first solo exhibition at KOW, Monsieur Zohore transforms the gallery into a climatological field—entering Whether the Weather, four oscillating ventilators Wirbelsturm Marianne, Susanne, Sabine, Hildegard turn their heads as if in greeting. Their motors hum, their blades slice through the space, and the gallery itself becomes alive with air currents, movement, sound, and presence. Visitors are swept along in the environment these mechanical actors create, as if the works themselves are taking their temperature. The ventilators observe, approach, and engage the audience: moving portraits and hurricanes, shaping both the physical and psychic climate of the space.

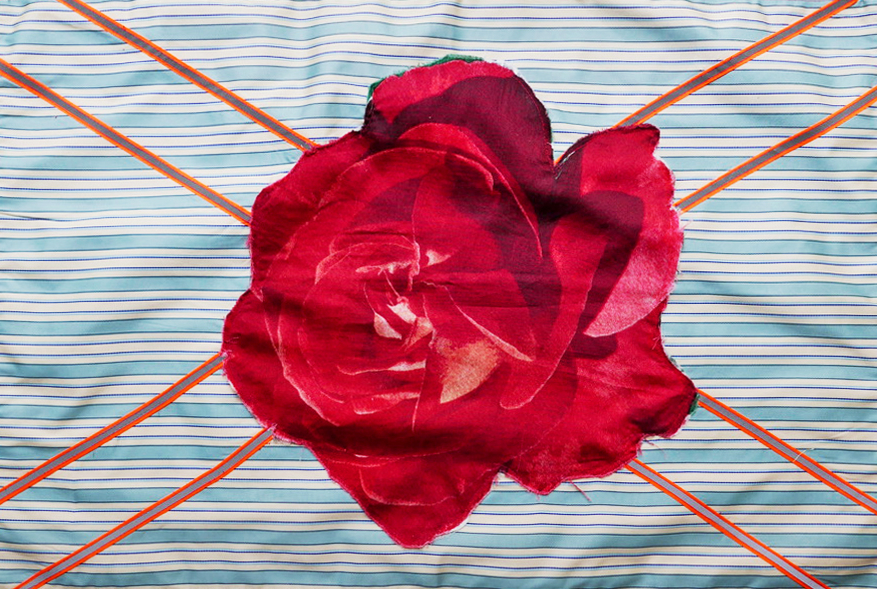

The exhibition unfolds as a shifting forecast, part archive, carnival and aquarium, bringing together fragments from myth and history, children’s rhymes, German and American popular culture. It is titled after an American tongue twister that insists on endurance, doubling as a forecast for the show. The Diva, a talking tree, queers the experience of weather, asking, “How will she treat you?”

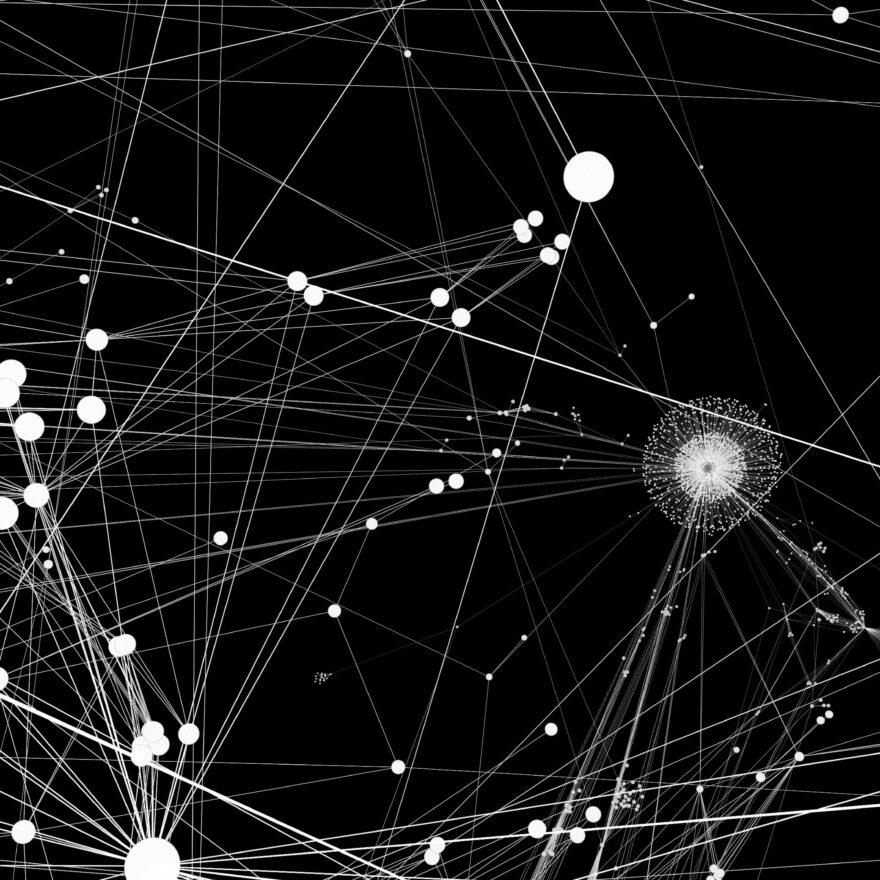

Zohore works like a documentarist of the everyday, his practice is an audit of culture: historical facts, mass-produced objects, bureaucratic tokens, and personal sightings are rearranged into provocative constellations. Paper towels, for instance, register as essays that absorb, record, and communicate the artist’s artists process. Digital images, collected ephemera, and quotidian objects are presented with a signature wit, inviting play and participation.

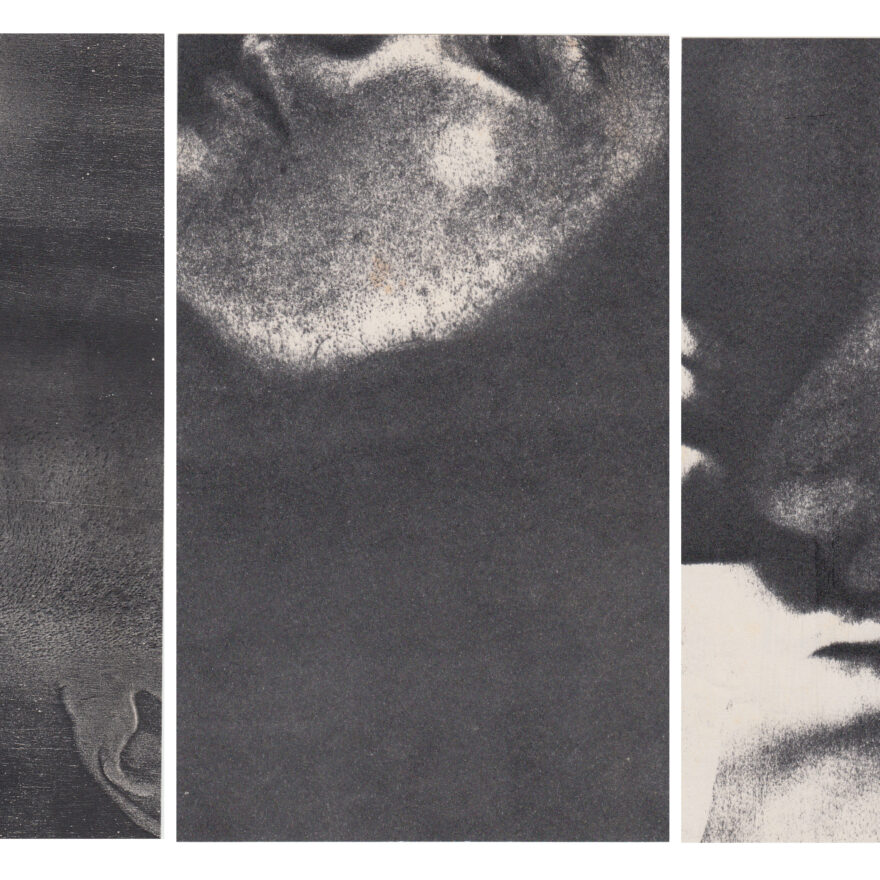

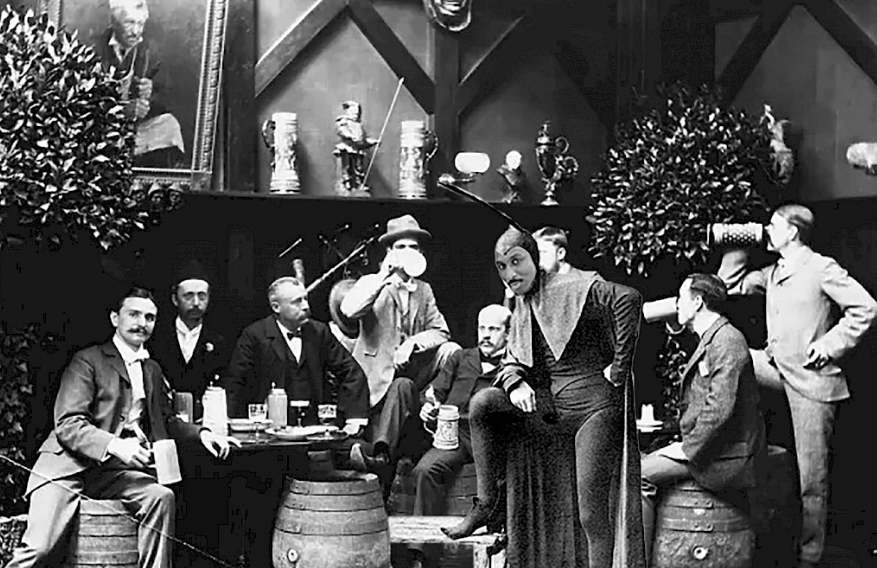

In Die!, Meerjungfrau, 1922–2025, Zohore assembles Nosferatu across three eras, Halle Bailey’s Black Little Mermaid, May Ayim, and the Iron Cross. Vampires, mermaids, and poets occupy thresholds where the human is narrated as monstrous or marvelous depending on who looks. In Fischers Fritze fischt frische Fische… a singsong German tongue-twister frays into violence: its playful cadence collapses beside an 1805 engraving of a slave ship, lists of invasive fish species, and Achenbach’s Romantic seascapes. Innocence in language masks a history of German colonial violence; “invasive” becomes a recurring motif, ecological, linguistic, and cultural. In these works, collage as method presses disparate climates together.

Across the exhibition, traces of German Romanticism are twisted into playful landscapes alive with voices, references, and figures. Zohore constructs crowded stages of association, generating his own mythologies of weathering through allegory, humor, and site-specific observation.To step into Whether the Weather is to feel multiple atmospheres enclosed together: fun and unsettling, lyrical and cutting. History arrives not as past event but as atmosphere, staining surfaces, saturating lungs, shaping how bodies move. Visitors are invited to brace the weather and imagine new forecasts.