Charlotte Posenenske, Sylvie Fleury, Sylvie Fleury & Angela Bulloch

3 MAY until 26 JUL 2025

Opening – 2 MAY 2025, 6-9 pm

At Wilhelm Hallen:

Charlotte Posenenske, Sylvie Fleury

At Fasanenplatz:

Sylvie Fleury & Angela Bulloch

For this year’s Gallery Weekend 2025, the work of Sylvie Fleury (*1961, Switzerland) will be highlighted with a two-part exhibition.

The first exhibition, a solo show by Sylvie Fleury at Mehdi Chouakri Wilhelm Hallen, explores the artist’s distinctive approach, including sculpture, painting, and installation. Fleury reinterprets concepts often associated with a masculine artistic language through a feminine lens, underlying gender power dynamics. Engaging boldly with pop visual culture, Fleury pushes the boundaries of form and medium while reflecting on artistic authenticity and vanity. Her work continues to explore consumerism, glamour, and fetishization, transforming familiar symbols into provocative artistic statements.

“Sylvie Fleury’s working method reflects the here and now as she responds seismographically to trends and sees through market mechanisms appearing in fashion and in magazines. Her feeling for the transient zeitgeist and her sensibility for the instruments of power of various subsystems of society, such as Formula One racing, the world of fashion and the art market or art history, expose with tongue-in-cheek humor and with visual persuasiveness value systems that need to be questioned. Accordingly, it is often clichés that she defeats using their own means. Markus Brüderlin tellingly describes Fleury’s approach as “femininity” rather than feminism: ‘With her aesthetics of softness, Fleury feminizes these objects in her art, without ever denying that this kind of femininity is itself a cliché’.”

– Verena Hein, exhibition catalog My Life on the Road, Villa Stuck Munich, 2016, p. 28

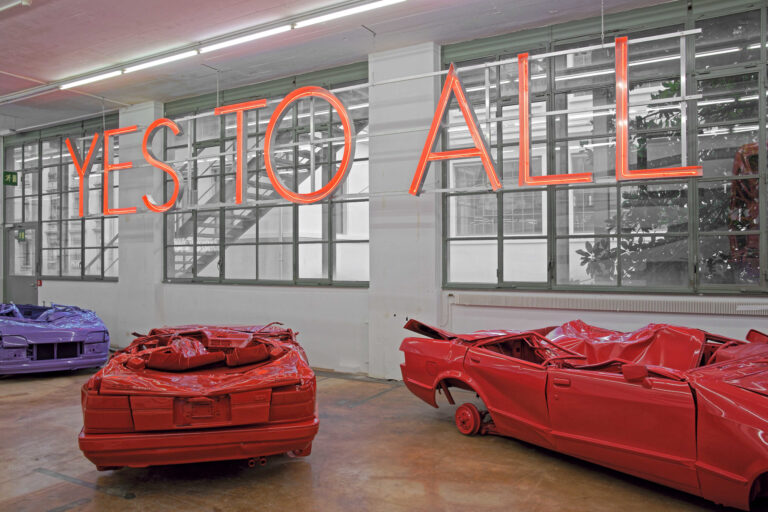

Sylvie Fleury

Yes to All, 2008

Courtesy of the artist and the MAMCO Museum Geneva

Sylvie Fleury

Precious Rocks (Attract), 2018

Acrylic on canvas

115,9 x 139,1 x 7,6 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Mehdi Chouakri Berlin

The second exhibition, held at Mehdi Chouakri Fasanenplatz, revisits the seminal 1993 show that first brought together Sylvie Fleury and Angela Bulloch (*1966, Canada) at Laure Genillard Gallery in London. In the early 1990s, both artists incorporated elements of pop culture—such as fireworks and karaoke—into collaborative works that playfully examined hedonism while critically interrogating the status of the artwork and the creative process itself. Titled The Art of Survival/Baby Doll Saloon, the exhibition at Mehdi Chouakri Fasanenplatz will showcase works originally conceived for the 1993 show, along with pieces from its 1999 reinterpretation at Mehdi Chouakri Gipsstrasse in collaboration with Gallery Esther Schipper.

“Artforum says that Bulloch ‘subtly disputes masculine logic’. I think she’s just having a whale of a time when art, thanks to the Americans, is beginning to be fun again. […] The artists [Angela Bulloch and Sylvie Fleury] have realised that art provides a zone from which to observe interesting cultural phenomena: they’re traditionalists, even while working a vein of anarchism. The idea that their work is fiercely feminist or wants to take apart power structures seems dubious. They’re enjoying themselves too much for that. This show leaves a distinct taste in the mouth which makes it convincing: it’s acidic, enjoyable but frustrating. I wanted ten times as much work, in a big gallery.”

– David Lillington, Time Out, May 5, 1993

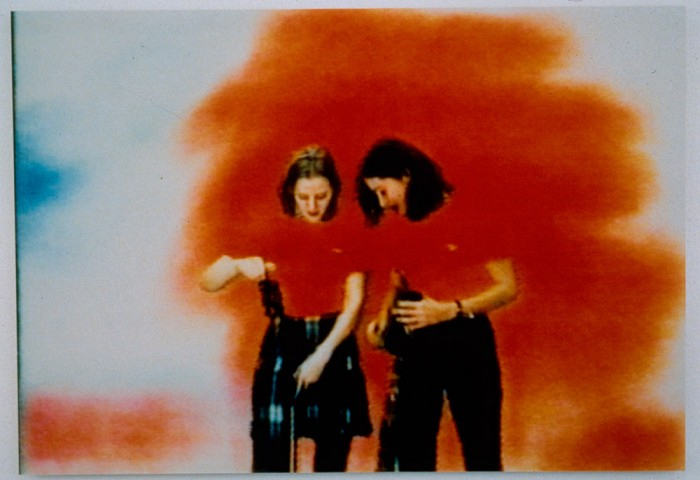

Sylvie Fleury & Angela Bulloch

Should I stay or should I go?, 1993/99

VHS colour video, 8 video stills, mounted on aluminium

Video 3’16 Min

Courtesy of the artists, Esther Schipper

and Mehdi Chouakri Berlin

Sylvie Fleury & Angela Bulloch

Should I stay or should I go?, 1993/99

VHS colour video, 8 video stills, mounted on aluminium

Video 3’16 Min

Courtesy of the artists, Esther Schipper

and Mehdi Chouakri Berlin

Additionally, the Archiv Charlotte Posenenske (1930–1985, Germany), a dedicated exhibition space at Mehdi Chouakri Wilhelm Hallen, will present a year-long display of lesser-known early works on paper and paintings by Charlotte Posenenske. For the Gallery Weekend 2025, the presentation will focus on paintings.